Many protozoan parasites can infect various organs and cause a range of diseases in dogs and cats that have varying impact based on patient health. Zoonotic implications are also a concern. This article summarizes major canine and feline protozoan infections, including clinical, diagnostic, and zoonotic features.

Intestinal Protozoa

Coccidia

Intestinal protozoan infections are a major cause of diarrhea, with Cystoisospora spp coccidia being among those most important.1,2 Cystoisospora spp are host-specific and have a direct life cycle. Cystoisospora canis and Cystoisospora ohioensis infect dogs,2 and Cystoisospora felis and Cystoisospora rivolta infect cats.1 Clinical coccidiosis is predominant in puppies and kittens; adults may act as subclinical carriers. Dogs and cats acquire infection by ingesting sporulated oocysts in the environment or by predating on paratenic hosts.1,2 Diagnosis can be achieved via detection of oocysts on a fecal flotation. Cystoisospora spp oocysts can be observed as ovoid elements, may vary in size, and can be found unsporulated or sporulated (ie, with the presence of 2 sporocysts, each containing 8 sporozoites). Diarrhea often occurs before oocysts are detectable in feces.1,2 Coccidia of dogs and cats are not a threat to public health, as humans cannot be infected.

FIGURE 1 Typical ovoid andunsporulated C canis oocyst (32-50 × 23-40 µm) found in the feces of a dog (40× magnification)2

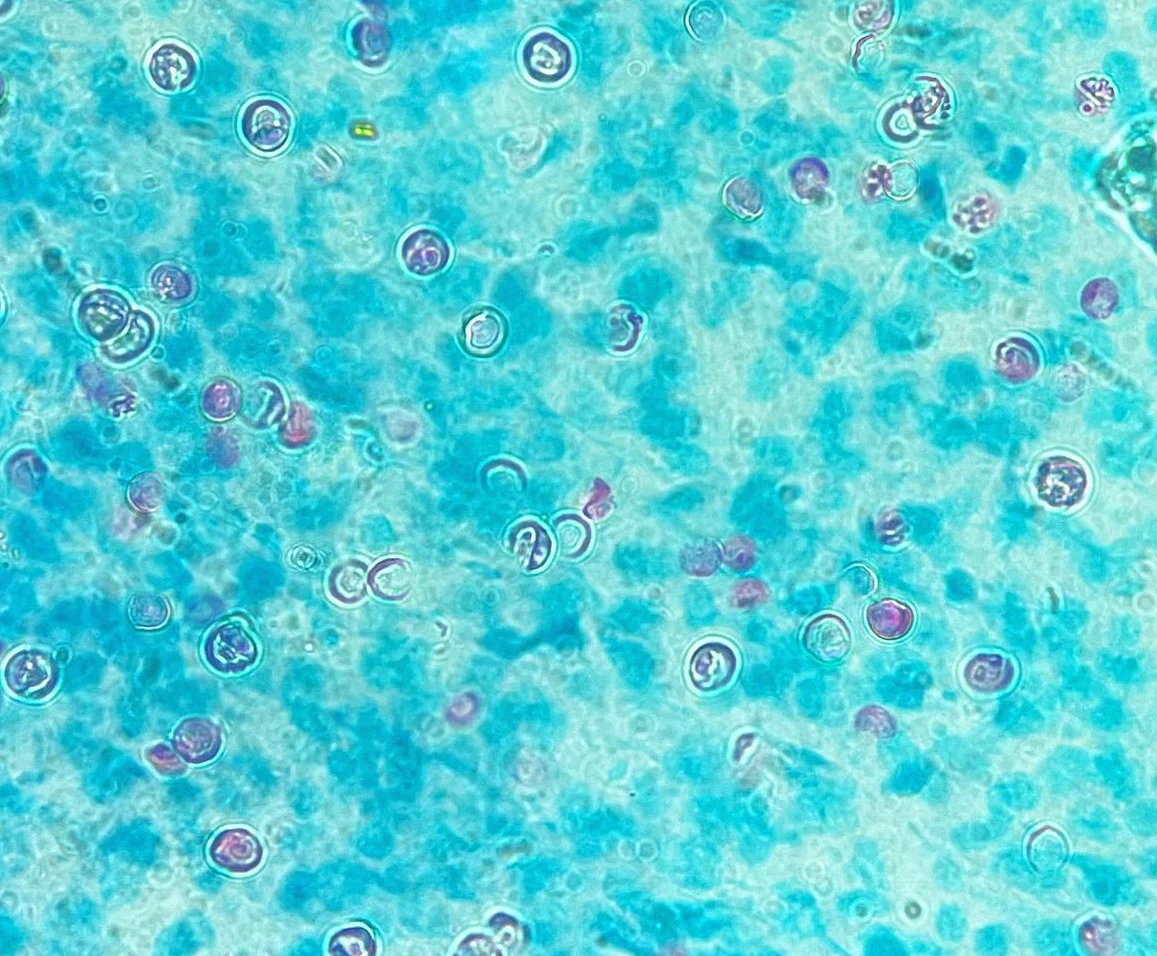

FIGURE 2 Typical ovoid andunsporulated C felis oocyst (32-53 × 26-43 μm) found in the feces of a cat (40× magnification)1

FIGURE 3 C ohioensis–like sporulatedoocyst (smaller than those of C canis, 17-27 × 14-24 µm), with a typical rounded shape containing 2 sporocysts found in the feces of a dog (40× magnification)2

FIGURE 4 Round and sporulated C rivolta oocyst (smaller than those of C felis, 23-29 × 20-26 μm) found in the feces of a domestic cat (40× magnification)23

FIGURE 5 Oval and unsporulated C felis and round and sporulated C rivolta found in the feces of a cat (20× magnification)

Giardia duodenalis

Giardia duodenalis is a common intestinal parasite. Different assemblages with variable host specificity have been described, and dogs and cats may be infected by nonzoonotic or zoonotic variations.3 G duodenalis has a direct life cycle. Trophozoites live in the small intestine where they alter the permeability, reduce absorption, and form the typical cysts shed in feces. Patients are infected via the fecal–oral route through ingestion of Giardia spp cysts.4 Infected dogs are often subclinical, but pasty/mucus-like diarrhea, vomiting, lethargy, weight loss, and/or loss of appetite are possible; overt disease is typically seen in cats.5,6 Diagnosis can be achieved via detection of cysts on a fecal flotation or sucrose gradient concentration; trophozoites may be found moving in fresh fecal smears. Zoonotic assemblages may circulate within dog and cat populations; however, risk for transmission to humans is low.3

FIGURE 6 Trophozoite of G duodenalis found in a fresh canine fecal smear (100× magnification); characteristic falling leaf motility, 2 nuclei, and flagella can be seen.24

FIGURE 7 Cyst (8-12 × 7-10 μm) of G duodenalis found in a canine fecal sample using sucrose gradient concentration (100× magnification)25; nuclei and the axostyle are visible.

Cryptosporidium spp

Cryptosporidium spp are common enteric protozoan parasites of small companion animals. The most frequently detected species are Cryptosporidium canis in dogs, Cryptosporidium felis in cats, and Cryptosporidium parvum in cats and dogs. Both cats and dogs may be infected by several other species with variable zoonotic potential. Cryptosporidium spp are waterborne parasites transmitted via ingestion of infective oocysts and can remain infective in water for several months.7 Infected immunocompetent patients are usually subclinical. Puppies and kittens may develop diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, and fever. Clinical signs (eg, dehydration, malabsorption, cachexia, death) are typically more severe in immunocompromised patients.8 Oocysts may be found on a fecal smear using Ziehl-Neelsen staining. Because oocysts of different Cryptosporidium spp are identical, copromicroscopy can only diagnose these organisms at the genus level. Zoonotic potential of C canis and C felis is low, and C parvum is high.9

FIGURE 8 Cytologic sample of canine intestinal mucosa showing Cryptosporidium sppoocysts (4-5 µm in diameter) in a Ziehl-Neelsen–stained smear; stained (purple to red) and unstained cysts are visible (40× magnification).9

Tick-Borne Hemoprotozoa

Babesia spp & Cytauxzoon spp

Babesia spp hemoprotozoa are major tick-borne parasites in dogs. The most important canine Babesia spp are large Babesia canis, Babesia rossi, and Babesia vogeli, as well as small Babesia gibsoni and B gibsoni–like.10Babesia spp are transmitted by different genera of ticks (eg, Rhipicephalus spp, Dermacentor spp, Ixodes spp, Haemaphysalis spp).11Babesia spp enter the bloodstream during the tick blood meal, and sporozoites invade the erythrocytes, differentiate into merozoites, and begin dividing, causing RBC lysis.12 Patients with canine babesiosis may range from subclinical to severe or fatal if not promptly treated. Clinical signs include fever (intermittent in chronic disease), jaundice, hematuria, lethargy, anorexia, anemia, myositis, and arthritis (chronic disease). Disease severity depends on the species involved.13,14 Although the other parasites listed have worldwide distribution, Babesia spp and Cytauxzoon spp have different and specific distribution in different areas of the world. Babesiosis in cats is considered rarer than in dogs in Europe, North America, and South America.13 Cats may be infected by Cytauxzoon spp hemoprotozoa. Cytauxzoon felis is present in the United States, and Cytauxzoon spp have been described in Europe.15 Romanowsky-stained blood smears may help with detection of Babesia spp and Cytauxzoon spp merozoites, although PCR confirmation is suggested. Babesia spp that affect dogs and cats are not considered zoonotic, and no description of human cases exist.

FIGURE 9 Merozoites of B canis inside an RBC (1.5-4.3 × 1.2-2.7 µm) on a blood smear of a dog (Romanowsky stain; 100× magnification); 4 pyriform piroplasms (pointed at one end and rounded at the other) are visible.

Hepatozoon spp

Hepatozoon spp blood parasites may infect dogs and cats. Hepatozoon spp infect patients via ingestion of an infected tick rather than during the tick blood meal. Hepatozoon canis and Hepatozoon americanum typically infect dogs. Adverse effects of H americanum may include fever, lethargy, loss of appetite, weight loss, and muscular pain. Patients with H canis are usually subclinical, but clinical signs (most commonly, fever, lethargy, and weight loss) have been described.16 Hepatozoon felis, Hepatozoon silvestris,and H canis infect cats.17 Patients with H felis are usually subclinical, but, when present, clinical signs include fever, jaundice, lymphopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. H silvestris may cause severe infections in domestic cats, with myocarditis, pulmonary edema, and intestinal intussusception described.18-20 Gamonts of H canis can be detected in Romanowsky-stained (or other rapid-staining methods) blood smears. For other species, muscle biopsy and/or PCR techniques are more sensitive. Canine and feline Hepatozoon spp are not considered zoonotic.

FIGURE 10 Gamonts (10-11 × 5-6 µm) of H canis detected in the cytoplasm of neutrophils in a blood smear of a dog (Romanowsky stain; 40× magnification). Gamonts have an ellipsoidal shape and a round or pleomorphic nucleus.26

Leishmania Infantum

Canine leishmaniosis is a worldwide, sandfly-borne disease caused predominantly by Leishmania infantum; other species (eg, Leishmania braziliense, Leishmania major) are also possible causes.21 After inoculation during the arthropod blood meal, the parasite invades skin macrophages and disseminates to the bone marrow, lymph nodes, liver, and spleen.22 Clinical signs include loss of appetite, weight loss, lethargy, epistaxis, blepharitis, keratitis/keratoconjunctivitis, uveitis, orbital cellulitis, extraocular muscle myositis, lameness, diarrhea, neurologic signs, and mucocutaneous signs (eg, ulcers, exfoliative/nodular/papular dermatitis, onychogryphosis, diarrhea).22 Feline leishmaniosis is rare but may cause similar clinical signs. Among other methods, diagnosis may be achieved by detecting L infantum amastigotes on lymph node cytology. L infantum can also be transmitted by sandflies to humans, causing visceral leishmaniosis, mostly in children and immunocompromised individuals.17

FIGURE 11 Amastigotes of L infantum infecting a macrophage in a dog (fine-needle lymph node aspiration cytology; Romanowsky stain; 100× magnification)

FIGURE 12 Periorbital alopecia in an English Setter with an L infantum infection (common in dogs with canine leishmaniosis)

Conclusion

Although intestinal protozoa are distributed worldwide and have a stable and cosmopolitan occurrence, distribution of tick-borne protozoa and L infantum is constantly changing and may spread into previously free areas. Regular screening for protozoan infections are therefore important to safeguard animal and human health.