Mast cell tumors (MCTs) are the most common cutaneous tumors in dogs, comprising 16% to 21% of all canine cutaneous tumors,1-4 and the second most common cutaneous tumors in cats.5

Background & Pathophysiology

The etiology of MCTs in dogs is largely unknown; however, chronic inflammation, alterations in tumor suppressor pathways, and altered expression of cell-cycle regulatory proteins and hormone receptors may play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.6-9

MCTs typically manifest in middle-aged to older dogs (mean, 8-9 years of age). Spay/neuter status does not appear to affect tumor development, and no sex predisposition has been identified.1-4 Predisposed breeds include beagles, boxers, golden retrievers, Labrador retrievers, Rhodesian ridgebacks, shar-peis, Staffordshire bull terriers, Weimaraners, and brachycephalic breeds.1,3,10-12

The etiology of MCTs in cats is unknown.

History & Clinical Signs

Canine MCTs typically manifest as solitary lesions in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue layers and primarily occur on the trunk or limbs.2,13-15 MCTs vary widely in clinical appearance (Figure 1). Well-differentiated MCTs are typically solitary, slow-growing lesions that can be present for several months to years and may be mistaken for benign growths (eg, warts, skin tags, lipomas).15,16 Poorly differentiated MCTs are commonly ill-defined, rapidly growing, ulcerated, and/or invasive masses.15,16 MCTs spread via the lymphatic system to regional lymph nodes, abdominal viscera, and, less commonly, bone marrow; spread of MCTs to the chest cavity (eg, lungs, intrathoracic lymph nodes) and other bodily locations is rare.10,13,15-17 Although many dogs diagnosed with MCTs do not show demonstrable clinical signs, a subset of dogs can demonstrate tumor-associated signs, including localized tissue reactions (eg, bruising, edema, ulceration, erythema) and/or systemic signs (eg, inappetence, vomiting, diarrhea, fever),15-21 secondary to the release of MCT granule substances, including histamine, heparin, and other vasoactive amines.

FIGURE 1A

Phenotypic variability of canine MCTs. MCT on the underside of the paw on a pelvic limb in a French bulldog (A). Metastatic cervical lymph node cluster in a crossbreed dog with a primary MCT on the lateral neck (B). Highly vascular and ulcerated MCT on the pelvic limb of a spaniel (C). Ulcerated, recurrent MCT on the lateral thorax of a terrier (D)

Feline MCTs have 3 general presentations: cutaneous, visceral/splenic, and intestinal.15,22-29

Feline cutaneous MCTs are solitary or multifocal dermal nodules or plaque-like lesions that occur predominantly on the head and neck and typically affect middle-aged cats.24,25,29-31,33 Two distinct histopathologic forms (ie, mastocytic and atypical/poorly granulated) have been identified; mastocytic MCTs can be further subdivided into well-differentiated and pleomorphic forms.34 Atypical/poorly granulated forms can spontaneously regress over time, while pleomorphic mastocytic forms may exhibit more variable behavior28,29,32-36; however, most solitary cutaneous MCTs are behaviorally benign regardless of their histopathologic classification and can be treated via surgical excision alone.24,25 Mitotic activity remains the most significant known prognostic factor for feline cutaneous MCTs.37 Anaplastic or recurrent tumors may require more aggressive treatment, similar to canine MCTs.24,25

Feline visceral/splenic MCTs are sometimes accompanied by cutaneous tumors, but cutaneous lesions are usually absent in cats with primary visceral disease.23,25 Systemic/internal dissemination is common in these patients, and most cats are clinically ill at the time of presentation.23-25

Intestinal MCTs are the third most common intestinal tumors in cats.36 Lesions can be focal, infiltrative, or diffuse and predominantly affect the small intestine.27,28 Patients are typically clinically ill on presentation.27,28

Diagnosis

Although many canine MCTs can be diagnosed using fine-needle aspiration and cytology, biopsy is required to provide definitive grading and additional prognostic information. Immunohistochemical stains may be necessary to distinguish poorly differentiated MCTs from other round cell tumors. Staging, including a minimum database (ie, CBC, serum chemistry profile, ± urinalysis), thoracic and abdominal imaging, and regional lymph node aspiration, should be considered in all dogs with MCTs. Complete staging is important for developing a treatment plan and providing an accurate prognosis in patients with multiple, recurrent (Figures 1D and 2), and/or large MCTs (Figure 3) and in dogs with MCTs in locations more likely to be associated with aggressive behavior (eg, oral cavity [Figure 4]; perineum; subungual, preputial/inguinal regions).10,13,15,16 Advanced imaging can help guide treatment planning (eg, surgery, radiation) in patients with large, fixed, and/or invasive tumors. Buffy coat analysis is not informative or specific for the detection of systemic MCTs or in monitoring response to therapy in dogs with MCTs, as the degree of mastocytemia in dogs without mast cell-related illness often exceeds that detected during tumor staging in dogs with MCTs.38 36

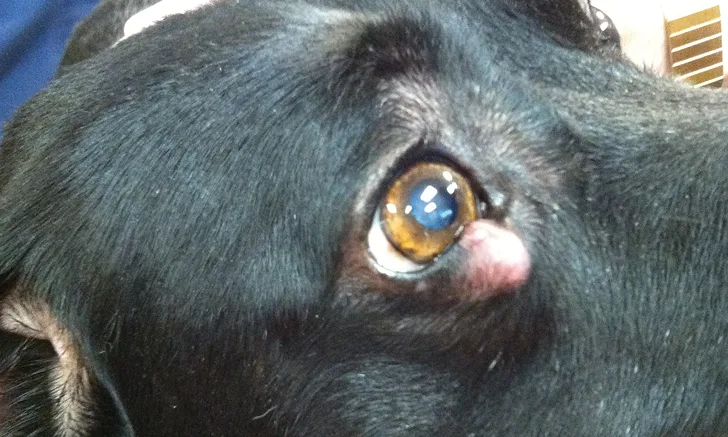

FIGURE 2

Ill-defined, recurrent periocular MCT in a Labrador retriever crossbreed

Cats that have multifocal, large, and/or rapidly growing cutaneous tumors, have palpable organomegaly, and/or are clinically ill at the time of diagnosis should be staged with a minimum database, thoracic and abdominal imaging, and buffy coat analysis ± organ (eg, liver, spleen) aspiration. In cats, buffy coat analysis can provide an index for assessing systemic disease at the time of diagnosis and monitoring response to therapy.39

There is no universally accepted MCT grading scheme for cats; however, a recently proposed grading system (see Grading Scheme for Feline MCTs) attempted to identify the small but significant subset of cats with cutaneous tumors that have increased potential for more aggressive behavior, including eventual widespread metastasis.40 Tumors classified as high-grade were associated with significantly reduced survival times (median, ≈1 year) as compared with tumors classified as low-grade (median not reached).40

Grading Scheme for Feline MCTs40

High-grade feline MCTs are characterized by

Mitotic count >5

and

Two of the following criteria

Tumor diameter >1.5 cm

Irregular nuclear shape

Nuclear prominence/chromatin clusters

Assess and update your understanding of mast cell tumors with this evidence-based quiz.

Treatment & Management

Surgical removal of tumors amenable to wide resection is typically the treatment of choice for cutaneous and subcutaneous canine MCTs. In dogs with large, ulcerated tumors, incisional biopsy can be considered for grading and treatment prior to definitive therapy. Lateral surgical margins of 2 to 3 cm and 1 fascial plane underlying the tumor are typically recommended when possible.41-49 Incompletely excised tumors can be treated with scar revision surgery or definitive radiation therapy to address microscopic residual disease. Marginal excision of small, low- to intermediate-grade tumors with circumferential margins of 3 to 4 mm (preferably 1 fascial plane deep) may be adequate in preventing local recurrence.42-46 High-grade MCTs have a higher risk for recurrence as compared with low-grade tumors (≈36% vs ≈4%), regardless of the histologic tumor-free margin.46 Nonsurgical and/or recurrent tumors can be treated with palliative radiation.50,51 Neoadjuvant radiation can also be used to shrink MCTs prior to surgical removal.

Chemotherapy can be considered for neoadjuvant therapy, postoperatively for incompletely excised tumors in which additional surgery or radiation is not elected or feasible, and for any high-grade or metastatic tumors. Various chemotherapeutic agents have been used alone or in combination in the treatment of MCTs, with overall response rates between ≈20% to 90%. The average response rate to chemotherapy in dogs with gross disease is ≈40%.52-65

For dogs with primary tumors <3 cm3, electrochemotherapy may be considered if surgery is not elected; a subset of these dogs may experience outcomes comparable with dogs treated surgically.66-68

Novel therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), are available for the treatment of MCTs. Approximately 25% to 30% of canine MCTs have activating mutations in the c-kit gene that can cause unregulated downstream signal transduction, which in turn promotes tumorigenesis.69-73 Activating mutations in the c-kit gene have been shown to correlate with increased local tumor recurrence, metastasis, and poorer prognosis.73,74 Toceranib phosphate is a veterinary-approved TKI with an overall biologic response rate of 60% and a median time to tumor progression of 4.5 months.75 Dogs with an activating mutation in the c-kit gene have increased response rates(up to ≈69%) to TKI therapy as compared with traditional injectable and oral chemotherapeutics used in the treatment of MCTs.74-79

Direct intratumoral injection of canine MCTs may be considered in select cases for smaller tumors (generally, <1-2 cm), for which surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy are not feasible or are declined. Intratumoral triamcinolone has a response rate of 67%, with a median time to progression of ≈2 months and minimal reported adverse effects.80 Tigilanol tiglate is a novel therapy FDA-approved for intratumoral injection of nonmetastatic subcutaneous MCTs located at or distal to the elbow or hock and for intratumoral injection of nonmetastatic cutaneous MCT in dogs and has a 75% complete response rate after the first injection, with two-thirds of dogs maintaining response up to 1 year posttreatment.82-84 Wound formation is anticipated at the injection site as part of the mechanism of action of tigilanol tiglate and typically develops within 7 days of treatment and resolves within a month with supportive measures.83

In general, dogs that have nonmetastatic, low-grade cutaneous MCTs may experience long-term tumor control or cure with surgery ± radiation therapy. Patients with several tumors (regardless of grade) or nonsurgical, recurrent, high-grade, and/or metastatic tumors may benefit from local therapy in combination with chemotherapy or TKI therapy.

Canine subcutaneous MCTs are generally associated with positive long-term outcomes, but more recent studies have identified a subset of subcutaneous MCTs that can behave more aggressively and have a poorer prognosis, specifically those with mitotic count >4, Ki67 index >23, ± an infiltrative growth pattern.85-87

Presurgical therapies that can help mitigate the effects of MCT degranulation in dogs with bulky tumors include H1 and H2 antagonists (ie, antihistamines), proton-pump inhibitors, corticosteroid therapy, and other medications (eg, sucralfate, misoprostol) to treat active or suspected gastric/duodenal ulceration secondary to MCTs.

In cats, surgery and radiation therapy are similarly viable treatment options for MCTs, although consensus regarding ideal surgical margins does not exist. It is generally accepted that, given the benign behavior of most feline cutaneous MCTs, even marginal tumor excision can provide excellent long-term outcomes in most patients.88,89 In cats with primary splenic involvement, including those with visceral metastasis, splenectomy is considered the standard treatment and can result in long-term survival with or without adjuvant chemotherapy.26 Cats with intestinal MCTs require wide resection of the primary lesion when possible. Although a chemotherapeutic standard for MCTs has not been definitively established, positive responses to predniso(lo)ne, lomustine, vinblastine, TKIs (eg, imatinib, toceranib), and chlorambucil have been reported.90-94 Cats with the c-kit gene mutation may have an increased chance for response to TKI therapy, but the impact of mutation status on overall prognosis does not appear to be significant as compared with dogs.95-97

Discussing Treatment Options for Mast Cell Tumors

Communicating effectively with clients about mast cell tumors (MCT) can be challenging. Clients should know their options, but expectations on both sides of the examination table need to be realistic—not every client will want or be able to pursue definitive treatment for a neoplastic lesion.

If a client chooses to forego treatment for an MCT, open communication about palliative care, quality of life, and expectations should be provided without judgment.

If a client is considering scheduling an appointment with an oncologist for further care, advance communication about cost and misconceptions is key, particularly because many clients have experience with human cancer care. Reaching out to the oncology team beforehand may help avoid misinformation that could cause friction during the referral process.

Research shows regret is more likely with rushed decisions. Clients should be given time to process information they are receiving, ask questions, and consider the options. It is essential to keep judgment out of the conversation. Concerns about a decision should be raised in an open and empathetic manner.

For more information, review these articles on Hospice Care & Palliative Sedation and Top 5 Tips for Veterinary Oncology Referrals.

Prognosis & Prevention

The prognosis for canine MCTs is variable. Most dogs with small, low- to intermediate-grade, nonmetastatic MCTs can experience long-term (ie, years) survival or, potentially, be cured with surgical treatment alone.10,15,16,41,42,46,47,49,50 Dogs with high-grade, metastatic, or late-stage disease have a guarded to poor long-term prognosis.6,10,15,16,18,19,49-65 There is no known prevention for MCTs in dogs. Early detection and treatment can help ensure a long-term, positive outcome; therefore, it is important to maintain an updated body map of patients and investigate all new nodules and masses, regardless of how innocuous the lesions may appear.

As in dogs, there is no known prevention for MCTs in cats. Most cutaneous MCTs in cats are behaviorally benign, with relatively low rates of local recurrence and metastasis (0%-24%).29-33 In cats with primary splenic MCTs, a median survival rate of 1 to 2+ years is possible postoperatively with splenectomy and with or without additional therapy.26 Prognosis has historically been considered poor for most cats with intestinal MCTs; however, a recent study reported a median survival rate of ≈1.5 years in cats treated with combination therapy (ie, surgery, chemotherapy, and corticosteroid therapy).91