Eleanor, a 1-year-old, 5.5-lb (2.5-kg), indoor-only, spayed domestic shorthair cat, was presented for a 2-month history of weight loss (≈2 lb [0.9 kg]) despite a good appetite and a 1-week history of increased respiratory effort. Use of routine preventives was not reported by the owner.

Physical Examination

On physical examination, BCS was 3/9, respiratory effort was mildly increased in both phases of respiration (ie, inspiration, expiration), and harsh bronchovesicular sounds were auscultated across all lung fields. Fundic examination was unremarkable. No other abnormalities were noted. The remainder of the physical examination was normal.

Differential Diagnoses

There are many differential diagnoses for increased respiratory effort and/or respiratory distress. Diseases affecting the pulmonary parenchyma (including infectious pneumonia, noninfectious pneumonia, pulmonary edema, neoplasia, pulmonary thromboembolism, and interstitial lung disease) were considered more likely for this patient because of the increased respiratory effort in both phases of respiration and increased harsh bronchovesicular sounds in all lung fields. Infectious pneumonia, noninfectious pneumonia, neoplasia, and interstitial lung disease were considered most likely based on the patient’s history of weight loss and duration of clinical signs.

Diagnostics

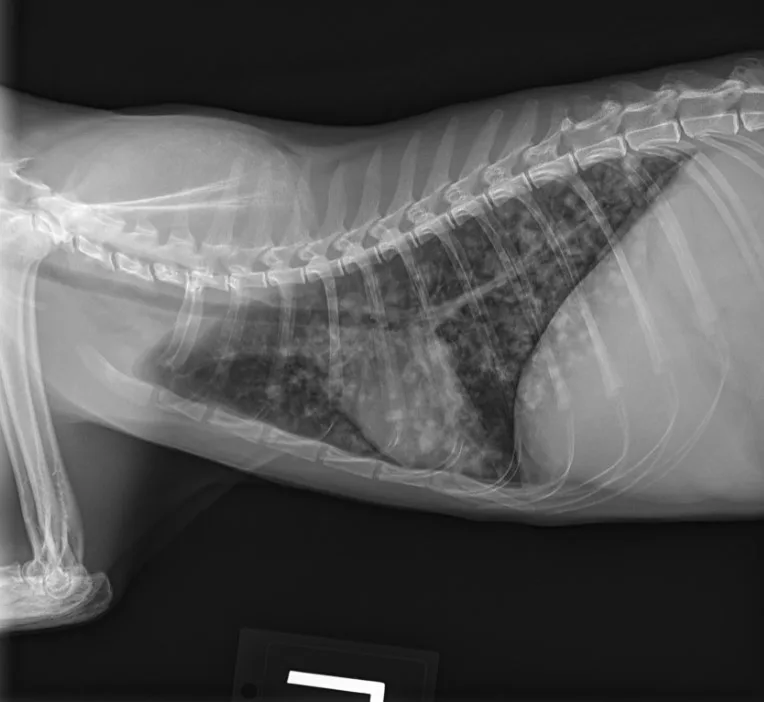

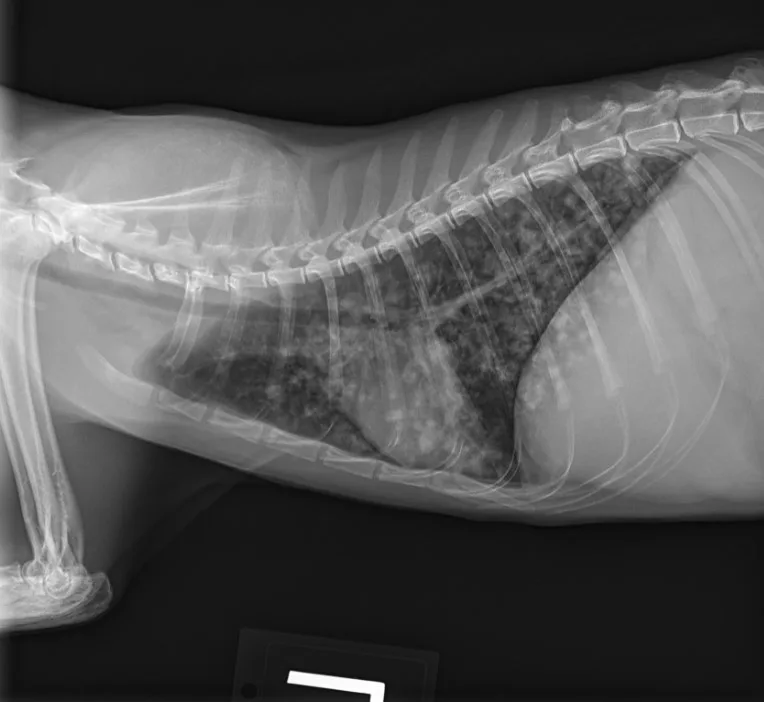

Butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg IV) was administered for sedation to obtain 3-view thoracic radiographs (left lateral, right lateral, ventrodorsal). Results revealed diffuse pulmonary nodular changes with an underlying bronchointerstitial pattern (Figure 1). Fungal pneumonia, parasitic pneumonia, neoplasia, and eosinophilic inflammatory disease were the most likely differentials for this pattern.

A

FIGURE 1 Left lateral (A), right lateral (B), and ventrodorsal (C) thoracic radiographs at the time of initial diagnosis. Diffuse pulmonary nodular changes with an underlying bronchointerstitial pattern can be seen.

CBC showed a mild, nonregenerative anemia. WBC count was within normal limits. Serum chemistry profile showed mild hypoalbuminemia and mild hyperglobulinemia. Urine specific gravity was 1.054; no other urine abnormalities were noted. Results for FeLV/FIV testing performed prior to referral were negative. Fecal and heartworm testing was not performed because a diagnosis had already been reached.

Table: Select CBC & Serum Chemistry Findings

With the patient under general anesthesia, bronchoalveolar lavage was performed, and analysis showed a normal cellular distribution, with 90% macrophages, 4% small lymphocytes, 3% neutrophils, and 3% eosinophils.1 The pathologist noted possible intracellular fungal organisms (suspected Histoplasma capsulatum) within macrophages, but there were too few cells of sufficient quality for definitive diagnosis. Samples of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were submitted for aerobic, anaerobic, and Mycoplasma spp cultures; results were negative. Urine was submitted for Histoplasma spp antigen testing based on cytologic suspicion; results were positive.

When a patient needs unexpected care, it can be tough to talk about money, but finances can be the deciding factor in many cases. Set these conversations up for success.

Provide a safe place for clients in a private room (not the waiting area), and have a seat together.

Acknowledge potential financial strain (if applicable) and offer partnership in seeking solutions.

Ask permission before offering suggestions.

Present small amounts of information, and pause to let the client absorb and formulate questions.

Include the rationale and benefit to the patient for the anticipated diagnostics and treatments.

For more, read the full article on Tools for Talking to Your Clients About Money.

Diagnosis: Infectious Pneumonia Caused by Histoplasma Capsulatum

Treatment

Empiric treatment with doxycycline (5 mg/kg PO every 12 hours) and fenbendazole (50 mg/kg PO every 24 hours for 14 days) was initiated pending BALF and culture results and discontinued after results were available. Itraconazole (5 mg/kg PO every 24 hours) was initiated after urine antigen test results were positive for histoplasmosis.

Due to the increased respiratory effort observed on physical examination and the severity of infiltrates visible on radiographs, concurrent glucocorticoid therapy (prednisolone, 0.5 mg/kg PO every 24 hours) was administered for 5 days, then tapered and discontinued over the following week. Itraconazole was continued, and a 1-month recheck was planned to evaluate physical status and re-evaluate thoracic radiographs. A serum chemistry profile was also planned at the 1-month recheck because hepatotoxicity is a potential complication of itraconazole.

Treatment at a Glance

Oral antifungal medications (eg, itraconazole, fluconazole) are a key component of therapy; treatment duration of at least 6 months is usually required.

Amphotericin B can be considered in severe, life-threatening situations, followed by oral antifungal therapy.

Concurrent use of glucocorticoids can be considered in cases of severe respiratory infection or with CNS or ocular involvement. Anti-inflammatory doses (prednisolone, 0.25-1 mg/kg PO every 24 hours) should be administered concurrently with antifungals for as short a duration as possible.

Prognosis & Outcome

1 Month

At the 1-month recheck, her weight had increased to 6 lb (3 kg); estimated BCS was 3/9. Physical examination showed a normal respiratory pattern, but increased bronchovesicular sounds were still present bilaterally. No fundic abnormalities were noted. Radiographs indicated subtle improvement of the diffuse nodular pulmonary pattern (Figure 2).

A

FIGURE 2 Left lateral (A), right lateral (B), and ventrodorsal (C) thoracic radiographs 1 month after initiation of itraconazole. Subtle improvement of the diffuse nodular pulmonary pattern can be seen.

Serum chemistry profile revealed normalized albumin and globulin, and no evidence of hepatotoxicity associated with itraconazole administration was noted. Itraconazole was thus continued.

2 Months

At the 2-month recheck, continued clinical improvement was observed. The owner reported Eleanor was doing well at home. Her body weight had increased to 8.3 lb (3.8 kg); BCS was 4/9.On physical examination, mildly increased bronchovesicular sounds were still present. Fundic examination results were normal. Thoracic radiographs showed continued improvement; remaining lesions were predominantly in the peripheral lung field with a more caudodorsal distribution (Figure 3).

A

FIGURE 3 Left lateral (A), right lateral (B), and ventrodorsal (C) thoracic radiographs 2 months after initiation of itraconazole. Remaining lesions (arrows) were predominantly in the peripheral lung field with a more caudodorsal distribution.

Serum chemistry profile results were within normal limits. Therapeutic drug monitoring confirmed that serum levels of itraconazole were within recommended guidelines. Itraconazole serum concentration levels were 2.4 micrograms/mL (therapeutic range, 2-7 micrograms/mL); therapy was continued without adjustment.

Continued Management

Rechecks were continued monthly with the primary care clinician. Recommendations for continued treatment and monitoring included monthly physical examination (including fundic examination), thoracic radiography, and serum chemistry profile. Urine Histoplasma spp antigen testing 3 months after initiation of treatment and monitoring every 3 months until results are negative was suggested. Continuation of itraconazole administration was suggested for a minimum of 6 months, with discontinuation delayed until clinical and radiographic resolution of disease and a negative urine Histoplasma spp antigen test result.

Discussion

Cause

Pneumonia can be classified as infectious or noninfectious. Differentials for infectious pneumonia include bacterial, viral, fungal, parasitic, and protozoal causes. Feline infectious pneumonia is most commonly associated with viral (eg, feline herpesvirus-1) or fungal causes, with bacterial pneumonia occurring less frequently and often as a secondary infection. In contrast, bacterial infection is the most frequently encountered infectious cause of pneumonia in dogs, with viral, fungal, and parasitic causes being less frequent.2,3 Protozoal pneumonia can occur in dogs and cats but is uncommon.3 Histoplasmosis is a more common cause of fungal pneumonia in cats than other fungal organisms; however, infection with other organisms (eg, Blastomyces spp) can occur.4

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs of infectious pneumonia may include cough, labored breathing, fever, lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, and/or nasal discharge. Cough is less common in cats than in dogs. With Histoplasma spp infections, disseminated disease is more common than localized disease; however, localized disease is more often associated with the lungs in cats and the GI tract in dogs.5

Ocular involvement is common, particularly in cats, so fundoscopic examination should be performed at the initial examination and during follow-up visits. Skin lesions, most commonly of the head and neck, may be seen in cats with histoplasmosis. Lymph node, bone, joint, abdominal and other organs, and CNS involvement are also possible with disseminated forms of histoplasmosis.4

Investigation

In cats presented with respiratory distress, the area of the respiratory tract that is involved should be localized quickly, and a differential diagnosis list should be generated. Physical examination findings, including the phase of respiration most severely affected and type of respiratory sounds, can help localize the cause of respiratory distress to the appropriate anatomic location. For example, infectious pneumonia involves the pulmonary parenchyma, and patients with pulmonary parenchymal disease are typically presented with mixed inspiratory/expiratory distress and increased harsh bronchovesicular sounds or crackles. In contrast, upper airway disease is often associated with stertor or stridor, depending on the cause of the distress, and a slightly slower, more purposeful pattern of breathing associated with inspiratory distress.

After the source of distress is localized (eg, pulmonary parenchyma in patients with infectious pneumonia), differentials for that area can be considered. Differentials for disease in the pulmonary parenchyma include infectious pneumonia, noninfectious pneumonia, pulmonary edema, neoplasia, pulmonary thromboembolism, and interstitial lung disease. Differentials should be prioritized based on patient history and physical examination findings. Further diagnostic testing is often required.

Thoracic radiography is the most widely available diagnostic tool for evaluating the respiratory system. Three-view radiography (right lateral, left lateral, ventrodorsal [or dorsoventral]) is recommended. Depending on the underlying etiology and severity, infectious pneumonia can be focal or diffuse and have any lung pattern. CT can provide more detailed information but requires that the patient be under general anesthesia with inspiratory breath holds during imaging for the best-quality images. Lung aspirates can be considered in cases in which lesion distribution appears conducive to obtaining quality samples. Large focal lesions (eg, mass lesions) or diffuse disease distributions are most likely to yield results. Bronchoalveolar lavage can be used to obtain samples for cytologic evaluation and culture (eg, aerobic, anaerobic, mycoplasma). Additional diagnostic testing is often guided by these findings. In the case example presented here, fungal antigen testing was performed on a urine sample. This test can also be used to monitor response to treatment. There is significant cross-reactivity between Histoplasma spp and Blastomyces spp antigens with the urine antigen test; therefore, the relative prevalence of these organisms in the geographic area of interest is important to consider.

Treatment

Therapy and management of feline infectious pneumonia depends on the underlying cause. In cases of viral pneumonia, treatment is mostly supportive (eg, hydration, nutrition), and treatment of secondary bacterial infections may be required.

Fungal pneumonia treatment relies on therapy with azoles, with the possible need for amphotericin B in severe cases. Itraconazole is the treatment of choice for histoplasmosis, particularly for mild to moderate cases. Fluconazole can be considered if itraconazole is not well tolerated or if the infection is in a site with poor penetration by itraconazole. In severe, life-threatening infections, amphotericin B can be administered initially, followed by azole therapy. Ketoconazole is not recommended typically, particularly in cats, as other azoles have better safety profiles.

Concurrent short-term use of glucocorticoids may be needed to reduce inflammation associated with dying organisms and should be considered in cases of severe respiratory disease, ocular or CNS infection, and severe disease that requires use of amphotericin B. An anti-inflammatory dose of prednisolone (0.25-1 mg/kg PO every 24 hours) or an equivalent injectable dexamethasone dose (0.025-0.1 mg/kg every 24 hours) should be administered for as short a duration as possible when giving glucocorticoids.2 Supportive care (eg, supplemental oxygen therapy, blood transfusion, nutritional support) individualized to the patient should also be administered as appropriate.

Bacterial pneumonia treatment involves antimicrobial therapy in addition to supportive care to address hydration and nutrition needs and to support mucus clearance. Protozoal pneumonia is uncommon; the most likely causative agent is Toxoplasma gondii, which typically responds well to targeted antimicrobial therapy (eg, clindamycin).3

Take-Home Messages

Physical examination findings (eg, respiration phase, respiratory noises) can often help quickly localize respiratory disease.

Infectious pneumonia includes viral, fungal, bacterial, parasitic, and protozoal causes. Bacterial infection is most often secondary in cats but a significant cause of primary infectious pneumonia in dogs.

Histoplasmosis can result in disseminated or focal disease. Focal histoplasmosis is more common in the lungs of cats and the GI tract of dogs.

Histoplasmosis treatment relies on azole antifungal therapy. In severe cases, amphotericin B may be used initially, followed by azole antifungal therapy.

Anti-inflammatory doses of glucocorticoids may be used for short-term therapy when administered concurrently with antifungals.

Monitoring during histoplasmosis treatment should include clinical history, physical examination, monthly radiography, serum chemistry profile to monitor for hepatotoxicity, therapeutic drug monitoring, and urine antigen testing every 3 months.

In cats, antifungal treatment should be continued until clinical disease is resolved and urine antigen testing is negative.

Spectrum of Care Spotlight

Complex cases like this ask a lot of clients and veterinary care providers. Many clients will not be able to pursue all recommended diagnostics and treatments for reasons they may or may not be willing to share.

Three experts shared advice on navigating these common but challenging situations in a Clinician’s Brief panel discussion on spectrum of care. Here are some of their tips.

Communicate diagnostics, treatment options, and risks to clients in a way that can be easily understood. Document these conversations in the medical record.

Provide a range of treatment options, and work with clients to develop the best approach according to their budget and the patient’s quality of life.

Ask clients to provide written consent (eg, signed discharge papers) when a treatment approach differs from the highest care standards.