Icterus & Pancytopenia in a Cat

Marion Haber, DVM

Adam J. Birkenheuer, DVM, PhD, DACVIM, North Carolina State University

Icteric mucous membranes. Photo courtesy of Dr. Leah Cohn

A 2-year-old, spayed, female domestic shorthair was presented for sudden onset of lethargy and depression.

History

The cat had a 1-day history of depression. Severe lethargy and vocalization were noted the morning of presentation. The patient was an outdoor cat with exposure to feral cats, one of which had recently been found dead with no signs of external trauma. The patient had no previous medical problems. Rabies and FVRCP vaccinations were current. She was receiving no medications or flea and tick preventatives.

Physical Examination

The cat was depressed and recumbent and vocalized when manipulated. Temperature was 103.7°F, pulse rate 220 beats/minute, and respiration rate 50 breaths/minute. Sclera and mucous membranes were icteric (Figure 1), and spleen, liver, and peripheral lymph nodes were mildly enlarged. All other physical examination findings were within normal limits.

Laboratory Evaluation

Initial evaluation included serum biochemical profile, urinalysis, and automated blood count. Abnormal results are presented in the Table. Thoracic radiographs identified a diffuse, mild interstitial pattern.

Table

Assessment

The list of problems includes acute onset of lethargy and depression, tachypnea, pyrexia, pancytopenia, icterus, hepatosplenomegaly, peripheral lymphadenomegaly, and interstitial lung disease.

Ask Yourself ...

What infectious diseases should be considered?

What differential diagnoses should be considered?

What are the differential diagnoses for pancytopenia?

What important component of a CBC has not been done?

Diagnosis

Cytauxzoonosis

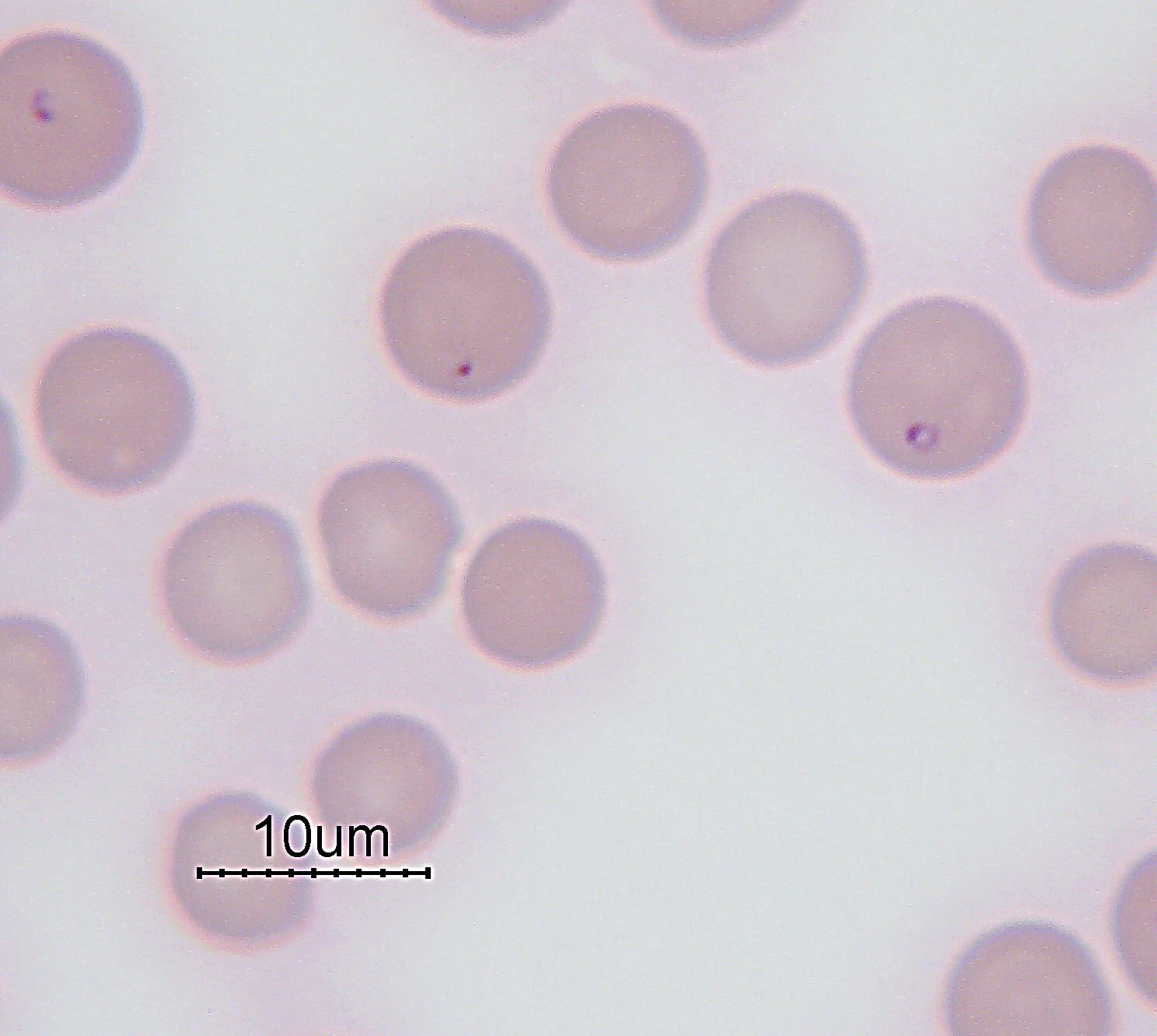

Small (1 to 3 µm), intracellular, signet-ring-shaped piroplasms consistent with Cytauxzoon felis were noted in red blood cells during microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained blood smears (Figure 2). A coagulation profile was consistent with DIC. Retroviral testing results were negative.

Laboratory abnormalities noted in this cat are typical of cytauxzoonosis. Liver enzyme activity is increased because of infiltration by infected macrophages and hypoxia secondary to anemia and ischemia. Hyperbilirubinemia is associated with hemolysis and hepatic dysfunction. Anemia is caused by immune-mediated hemolysis and destruction of red blood cells by parasite replication. Leukopenia is likely secondary to increased tissue demands and increased neutrophil margination. Thrombocytopenia is due to consumption secondary to DIC.

Intraerythrocytic piroplasms noted on microscopic blood smear examination (arrows).

Fluids, Heparin, & Imidocarb

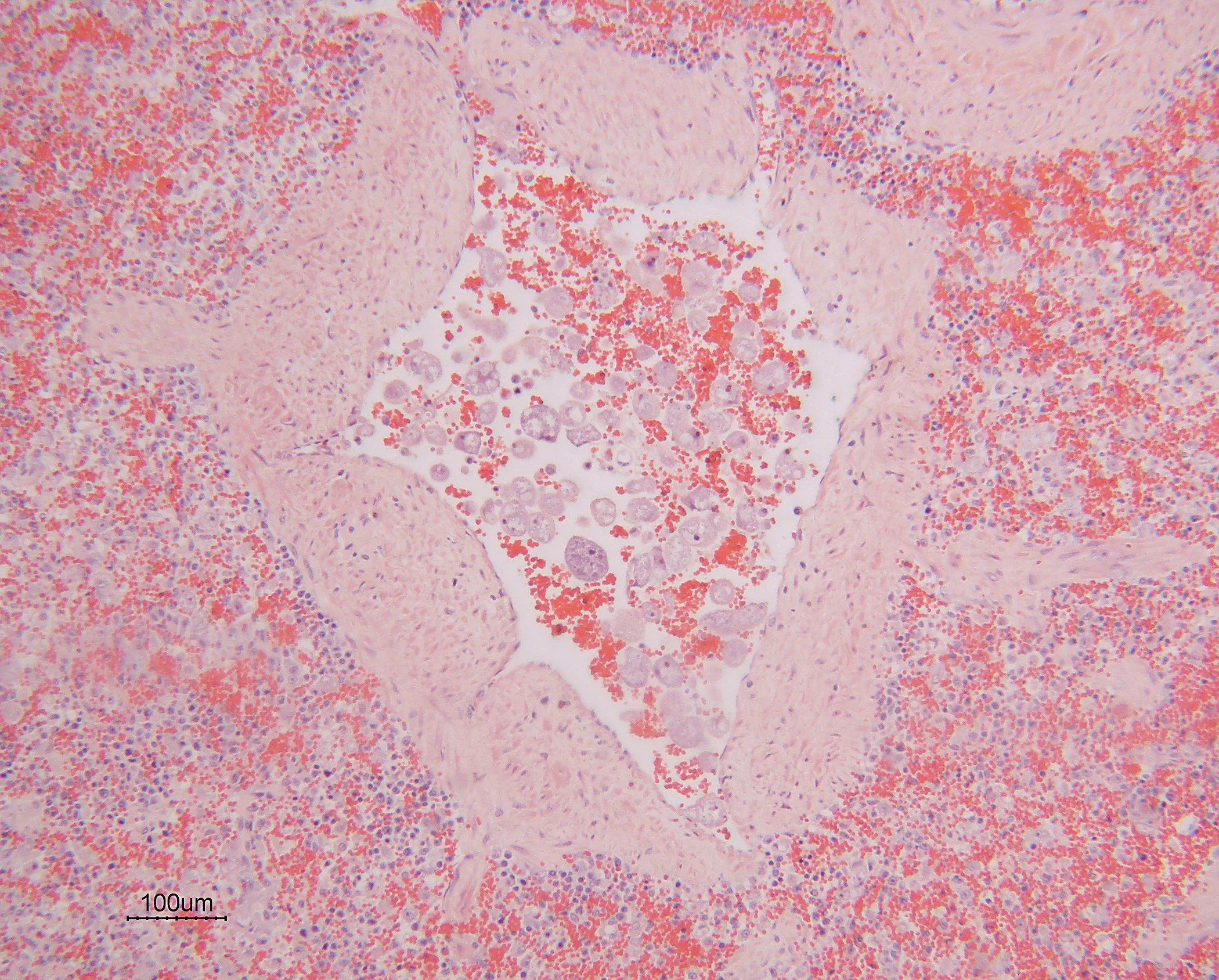

In this case, treatment consisted of intravenous fluids, heparin, and imidocarb dipropionate. Despite treatment, the patient became severely dyspneic and nonresponsive, and the owners elected euthanasia. Histopathologic evaluation of tissues confirmed the diagnosis of C. felis by revealing schizont-laden macrophages occluding small vessels and infiltrating the parenchyma of spleen, lung, and bone marrow (Figures 3 and 4).

Cytauxzoon felis has been experimentally transmitted by the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis. Infection is more prevalent during the summer months when ticks are most active. Bobcats are the primary reservoir hosts. Interestingly, several reports have included multiple infected cats from the same household or geographic region. The prognosis is usually grave; however, a nonfatal form of cytauxzoonosis has also been reported.

FIGURE 3

Occlusion of splenic vasculature with macrophage laden with schizonts (arrow).

Did You Answer ...

FeLV, FIP, FIV, cytauxzoonosis, mycoplasmosis (formerly hemobartonellosis), and ehrlichiosis.

Hemolytic anemia, sepsis, FIP, cholangiohepatitis, cholangitis, pancreatitis, hepatic neoplasia, and acute hepatic necrosis. In a febrile patient, inflammatory and neoplastic causes of icterus should be considered more likely.

Pancytopenia frequently results from decreased production of cells in bone marrow. Retrovirus-induced bone marrow suppression, immune-mediated destruction, neoplastic myelophthisis, myelofibrosis, or bone marrow necrosis are all differential diagnoses. Other than decreased production, destruction, sequestration, and/or utilization of cells in the periphery should be considered.

A microscopic blood smear examination should be part of every CBC because it confirms the accuracy of reported total cell counts. It can also provide important information on white blood cell differential counts and morphologic characteristics of red blood cells, and aid in identification of platelet clumping and red blood cell agglutination, which can cause artifacts in automated data. Lastly, blood-borne pathogens may be recognized. In this case, intracytoplasmic red blood cell organisms consistent with Cytauxzoon felis were identified (Figure 2).

Identification

During the first stage of the C. felis life cycle, organisms develop and replicate in mononuclear cells. These macrophages occlude small vessels and capillaries and are responsible for most clinical signs. These macrophages are occasionally identified on blood smears; however, they are more frequently noted in tissue aspirates or biopsy samples. During the second stage of the life cycle, organisms invade and replicate within red blood cells and should be distinguished from Mycoplasma haemofelis, Howell-Jolly bodies, and Babesia felis. Identification of the tissue phase or molecular testing is required to definitively distinguish C. felis from B. felis; however, B. felis has not been recognized in North America. Molecular tests will be available in the future to diagnose and differentiate these infections.

Early diagnosis and treatment may be associated with improved prognosis. Since the schizogenous phase occurs first, tissue aspirates or biopsies may be a better tool for early diagnosis. Practitioners should consider cytauxzoonosis as a differential for cats with any or all of the following signs: icterus, fever, lethargy, tachypnea, anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, or pancytopenia.

TX at a Glance

Fluid therapy: replacement fluid (e.g., lactated Ringer's solution)

Imidocarb dipropionate: 2 mg/kg IM, repeat injection in 3 to 7 days. (Pretreatment with atropine may reduce side effects.)

OR

Diminazine aceturate: 2 mg/kg IM, repeat injection in 3 to 7 days. (Pretreatment with atropine may reduce side effects.)

Heparin: 100-150 U/kg SC Q 8 H for treatment and prevention of DICOR

Fragmin: 100 U/kg SC Q 8-12 H

Oxygen therapy: as needed

Blood transfusion: as needed for anemia