Profile

Nephroliths

Clinical signs are often absent, although hematuria without lower urinary tract signs may be observed (see Diagnostic Imaging & Clinical Signs).

Calcium oxalate and struvite are the most common nephroliths.

Related Article: Feline Urolithiasis

Calcium Oxalate

Most common in older cats

Renal diets may slow or preventfurther growth. Urinary tract infection (UTI) must be ruled out (ie, urinalysis, urine culture and sensitivity).

Management

Monitoring (with imaging) renal function and nephrolith size and location

Invasive treatment is not recommended if urolith size and location remain stable.

If nephroliths cause an obstructive uropathy (diagnosed with ultrasonography [pyelectasia/hydronephrosis] ± antegrade pyelography) or bacterial pyelonephritis (diagnosed with ultrasonography [pyelectasia] ± cytology and culture of urine and/or renal pelvic fluid aspirate), consider:

Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy

Surgery (nephrotomy/pyelotomy); nephron damage and decreased renal function may occur.

Struvite (Magnesium Ammonium Phosphate)

Management

Medical dissolution diets and long-term antibiotic treatment based on urine culture and sensitivity results

Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy

Surgery (nephrotomy/pyelotomy); nephron damage and decreased renal function may occur.

Related Articles: Nutritional Management of Urolithiasis

Ureteroliths

Most common ureterolith is calcium oxalate, especially in older cats with chronic kidney disease.

Ureteral obstruction may be the cause of an acute-on-chronic crisis.

Calcium Oxalate

Management

Noninvasive medical management includes rehydration, correction of electrolyte and acid–base imbalances, promotion of urolith migration toward the bladder (eg, CRI mannitol to induce diuresis, prazosin, glucagon, amitriptyline).

Pain management

Ureteral stent placement

Nephrostomy tube placement

Surgery (ureterotomy)

Ureteral stricture is a common complication.

Surgery is contraindicated if the ureterolith is migrating, azotemia is decreasing, or the kidney is already dysfunctional.

Cystouroliths

Common clinical signs include pollakiuria, dysuria/stranguria, hematuria, and periuria.

Can be subclinical

Most common cystouroliths are struvite, calcium oxalate, urate, calcium phosphate, cystine, and silicate.

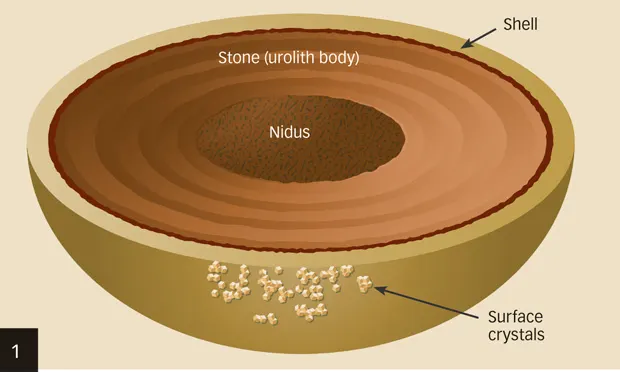

Determining urolith type helps guide management options (Figure 1, above; Table).

Complications of cystouroliths may include UTI, polyps, and obstructive uropathy.

Management

Medical dissolution (struvite, urate, cystine)

Cystotomy

Voiding hydropulsion (depends on urolith size, shape)

Catheter retrieval (depends on urolith size, shape)

Basket retrieval (depends on urolith size, shape)

Lithotripsy

Figure 1. Uroliths are often composed of a nidus or nucleus, body, shell, and possibly surface crystals. In urolith analysis, all components should be considered when directing treatment and prevention. For example, a calcium oxalate nidus and body may later develop a struvite shell and struvite surface crystals secondary to a complicating UTI; in this case, after the stone has been removed and the UTI eradicated, treatment strategies should target prevention of calcium oxalate urolith recurrence.

Urethral Uroliths

Most common in male dogs and cats

Clinical signs include dysuria/stranguria, hematuria, and urethral obstruction.

Management

Retropulsion followed by cystotomy

Antegrade voiding hydropulsion

Lithotripsy

Urethral stent placement

Cystostomy tube placement

GREGORY F. GRAUER, DVM, MS, DACVIM, is professor and Jarvis chair of medicine in the department of clinical sciences at Kansas State University. He has served as professor and section chief of small animal medicine at Colorado State University and faculty member at University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he completed his internship and residency and earned his MS. His area of interest, research, and teaching is the small animal urinary system. Dr. Grauer earned his DVM from Iowa State University.