Urinary Catheter Placement in Dogs

Lisa L. Powell, DVM, DACVECC, BluePearl Veterinary Partners, Eden Prairie, Minnesota

Urethral catheterization may be necessary in the treatment of some dogs. Critically ill dogs may require urethral catheterization for measurement of urinary output, secondary to urinary tract trauma, and/or due to recumbency, urinary obstruction, and/or neurogenic urinary disease.

Urethral Obstructions

Dogs that have urethral calculi causing urinary obstruction require catheterization to attempt retropulsion of calculi back into the urinary bladder and maintain patency until cystotomy and stone removal can be performed. Bladder and urethral tumors can also cause urethral obstruction, necessitating catheterization. Temporary urinary catheters are removed following procedures such as imaging or urinary bladder drainage and collection, whereas indwelling urinary catheters remain in place and are attached to a sterile closed urinary system for continued monitoring and care.

Foley Catheter

Foley urinary catheters are preferred in intensive care patients that require an indwelling catheter. These catheters have a balloon near the distal end that allows the catheter to remain in place without the use of external sutures. Once the catheter is passed in the urinary bladder, the balloon is inflated and situated at the neck of the bladder to secure it in place. The approximate length of the catheter from the urethral opening to the bladder should be estimated prior to catheter placement to determine how far to advance the catheter.

Placement of a Foley catheter in male dogs is more straightforward than in female dogs. In female dogs, sedation is often necessary and a urinary catheter can typically be placed through blind palpation; however, in smaller female dogs or when there is difficulty placing the catheter, a speculum can be used to help visualize the urethral opening. The urethral opening is located on the ventral vestibule wall directly on the midline under a bridge of tissue (ie, urethral tubercle). In some dogs, the urethral opening is close to the external vestibule opening; in others, it is more cranial and may be closer to the pelvic floor. Catheter placement in the urethral opening is successful when the catheter passes without obstruction and cannot be felt with the finger of the nondominant hand dorsal to the urethral opening. If a mechanical obstruction (eg, urethral stone) is encountered during catheter placement, retropulsion can be instituted to attempt to move the stone into the bladder. If the urethra is obstructed by a tumor, a urethral bypass procedure (eg, placement of a cystostomy tube) may be required. Multiple attempts at catheter placement may be required, and, in some female patients, urinary catheter placement may not be successful. Sedation, proper patient positioning, and knowledge of the anatomy of the urethral opening on the floor of the vestibule can help increase the chance for successful catheter placement.

Aseptic Technique

Aseptic technique should be used when placing a urinary catheter in dogs and is paramount to helping prevent secondary infection; it should include use of sterile gloves and sterile lubricant and antibacterial preparation of the urethral opening. The exposed catheter should be cleaned with a dilute antibacterial solution every 8 hours or when gross contamination is noted. When a closed-collection system is attached, care must be taken to keep all connections sterile and avoid contamination when emptying the urinary bag. When asepsis is adhered to, there is a relatively low risk for secondary infection from placement of a urinary catheter. Culture of the urinary catheter postremoval is not warranted, and a positive culture result is often a result of catheter colonization rather than true bacterial UTI.1

Step-by-Step: Urinary Catheter Placement in Male Dogs

What You Will Need

Sterile gloves

Antibacterial scrub solution

Sterile lubricant

Foley catheter (red rubber catheter for smaller patients)

Sterile water (for Foley catheter balloon inflation)

Urinary collection system

± sedation

± sterile saline flush, if the patient requires retropulsion of urethral calculi

Step 1

Place the sedated patient in lateral recumbency, and extrude the penis.

Author Insight

Do not hold the base of the prepuce tightly, as this could occlude the urethra and cause difficulty when trying to pass the catheter.

Step 2

Cleanse the urethral opening with an antibacterial solution.

Author Insight

If the Foley catheter is not packaged with a stylet, place a stylet in the catheter prior to catheter placement. Inject sterile saline into the catheter; this allows the stylet to be inserted with less resistance and enables easier removal of the stylet once the catheter is placed in the urinary bladder.

Step 3

Lubricate the end of the catheter with sterile lubricant, then advance the catheter into the urethral opening. Hold the catheter near the end to allow for easier entry into the urethra.

Step 4

Confirm the catheter has been placed in the urinary bladder by observing urine flowing out of the catheter, then inflate the Foley balloon with sterile water.

Author Insight

The amount of sterile water to infuse is labeled on the side of the distal end of the catheter.

Step 5

Pull the catheter distally until taut, ensuring proper placement of the balloon at the neck of the bladder/proximal urethra.

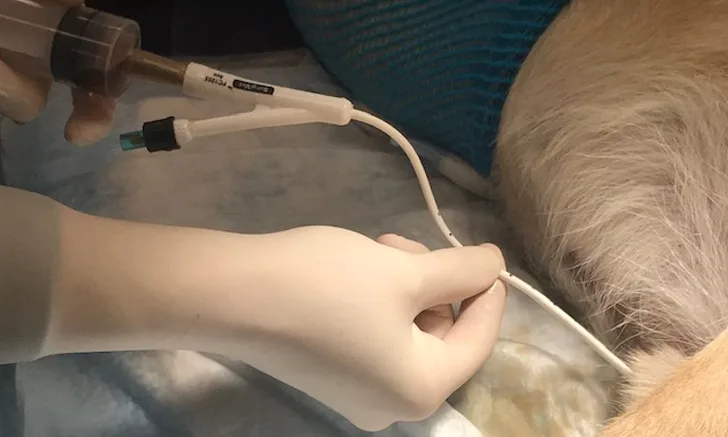

Step 6

Use a catheter-tip syringe to empty the bladder and collect urine for analysis.

Step 7

Connect the catheter aseptically to a closed urinary collection system.

Step-by-Step: Urinary Catheter Placement in Female Dogs

What You Will Need

Sterile gloves

Clippers

Sterile lubricant

Foley catheter (red rubber catheter for smaller patients)

Sterile water (for Foley catheter balloon inflation)

Speculum

Urinary collection system

Sedative

± towel

± sterile saline flush, if the patient requires retropulsion of urethral calculi

Step 1

Place the sedated patient in ventral recumbency with the pelvic limbs draped over the end of the table. Use a rolled towel to support the hip region and provide comfort and stability. Use clippers to remove excess fur from around the outer vulvar/urethral area.

Step 2

Using the nondominant hand, occlude the vestibule by placing a finger dorsal to the urethral opening. Insert the catheter. Once the vestibule has been entered, direct the catheter ventrally to find the urethral opening.

Author Insight

If the catheter passes the finger that is occluding the vaginal vault, the urethral opening has likely been missed and the catheter should be withdrawn a few centimeters, redirected, and advanced until it enters the urethral opening.

Step 3

While keeping the finger of the nondominant hand in place, advance the catheter into the bladder once the urethral opening has been entered.

Author Insight

The catheter should not be palpable under the finger if it is in the correct location.

Step 4

Inflate the balloon of the Foley catheter, and pull the catheter distally until taut, ensuring proper placement in the urinary bladder. Remove urine from the bladder for analysis, then aseptically attach the catheter to a closed urinary collection system.

The author would like to thank Maggie Slawson, CVT, for demonstrating proper urethral catheterization technique in the photos.