Renal Biopsy - When & Why

You have asked…When should I consider performing a renal biopsy?

The experts say…

Renal biopsies obtain information that can help a clinician manage a patient’s illness more astutely than is possible without a biopsy, allowing the best possible outcome. Information obtained may help in the diagnosis of a nephropathic illness for which specific therapeutic options exist. In addition, renal biopsies typically yield information about severity, activity, chronicity, or reversibility of pathologic changes, which supports clinical decision making about prognosis and treatment.

To achieve these purposes, 3 conditions must be met:

First, the biopsy must be indicated—that is, the results of the biopsy must have potential clinical utility.

Second, the biopsy procedure itself (the process of obtaining adequate samples) must be done safely.

Third, the tissue samples must be evaluated by individuals who have expertise in nephropathology and use all methods necessary to adequately characterize the pathologic changes in the specimens. Such analysis produces the most informative diagnosis.

IndicationsRenal biopsy may be considered for patients with acute kidney injury, glomerular disease manifested by proteinuria (ie, protein-losing nephropathies), and chronic kidney disease (Figure).

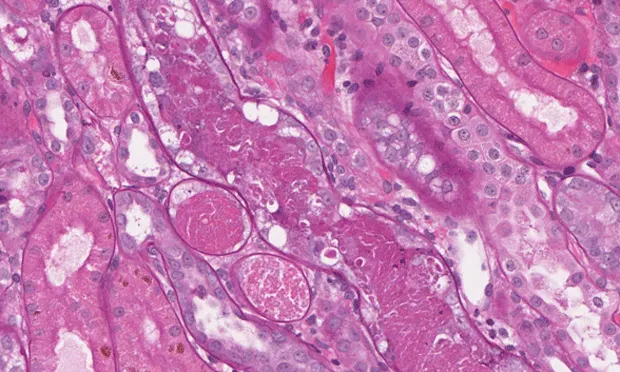

Photomicrographs illustrating conditions diagnosed with the aid of renal biopsy: (A) cortical tubules containing only necrotic debris (acute tubular necrosis) but with preservation of intact tubular basement membranes (periodic acid–Schiff stain; original magnification, 200×);

(B) glomerulus that contains multiple deposits of amyloid (Congo red stain; original magnification, 360×); (**C) glomerulus that exhibits features of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (periodic acid–Schiff stain; original magnification, 300×); and (D)** glomerulus that exhibits features of membranous glomerulonephropathy (periodic acid–Schiff stain; original magnification, 300×).

Acute Kidney Injury

Acute kidney injury can generally be categorized as acute nephritis or acute nephrosis. Nephritis is marked by clinical evidence of an inflammatory process at the systemic level (eg, fever, hematologic changes) or in the urinary tract (eg, urinalysis findings). In animals with acute nephritis, there often are sufficient grounds for presumptive diagnosis of a disorder (eg, leptospirosis) that can be managed without a biopsy. However, when there is recent, active, and ongoing injury due to an uncertain cause, a renal biopsy should be strongly considered.

Nephrosis is usually due to some toxic or ischemic cause. Few causes of acute nephrosis (eg, ethylene glycol toxicity, other crystal-associated forms of tubular injury) can be identified on the basis of biopsy findings. Even when a cause is identified, the finding rarely has direct therapeutic implications (administration of specific therapy versus continuation of nonspecific or supportive therapy). In this setting, a biopsy can exclude other possibilities when the etiopathogenic diagnosis is in doubt, but usually assesses the severity and potential reversibility of changes. In some situations, this prognostic information can affect clinical decisions about whether to continue care, which often is difficult and expensive, in hopes of a favorable outcome.

Protein-Losing NephropathiesAnimals with protein-losing nephropathies may be subdivided into different categories: nephritic or nephrotic glomerulopathies and glomerular disease characterized by persistent subclinical renal proteinuria.

Nephritic glomerulopathies are characterized by proteinuria that can vary in magnitude but often is in the nephrotic range (arbitrarily defined as urine protein–creatinine ratio > 3.5), with or without mild to moderate hypoalbuminemia, and urinalysis findings that include signs of inflammation in the urinary tract (such as microscopic hematuria and mild pyuria). Most animals with nephritic glomerulopathies exhibit mild to severe azotemia that typically shows a rising trend in acute cases.

Severe, difficult-to-control hypertension is often present, but edema or ascites is uncommon. Most nephritic cases are associated with glomerular diseases that feature extensive endocapillary inflammation, such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, particularly during the early phases. In animals with acute, rapidly worsening nephritic glomerular diseases, aggressive treatment may be justified if the diagnosis is well established in part by biopsy findings.

Nephrotic glomerulopathies exhibit nephrotic-range proteinuria associated with marked hypoalbuminemia that may be accompanied by evident edema or third-space accumulation of transudates (eg, ascites, pleural effusion). Affected animals usually have inactive urine sediments and often do not have azotemia, especially early in the disease. Hypertension is a variable feature of nephrotic glomerulopathies.

Most nephrotic cases are associated with glomerular diseases, such as membranous glomerulonephropathy, that disrupt visceral epithelial cell (ie, podocyte) function while causing little or no endocapillary inflammation. Amyloidosis also often produces marked proteinuria that is not accompanied by glomerular inflammation. For nephrotic glomerulopathies, the goals of biopsy are to obtain an accurate diagnosis and to assess indicators of disease severity or activity that correlate with prognosis or response to treatment.

Persistent subclinical renal proteinuria (proteinuria that is not of prerenal or postrenal origin and has been repeatedly documented over a month or more in an animal with no related clinical signs) may be of any magnitude. However, it is usually mild to moderate and associated with normal or mildly decreased circulating albumin concentrations. These animals may or may not be azotemic.

This category overlaps with chronic kidney disease, especially in International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) stages I and II and early stage III. These are among the most challenging animals in which to decide whether a biopsy will be useful. In general, the higher the urine protein–creatinine ratio and the lower (ie, more normal or near-normal) the serum creatinine concentration, the better supported the recommendation for biopsy.

However, each case should be considered individually instead of applying any one urine protein–creatinine ratio or serum creatinine cutoff. In borderline cases, biopsy seems the logical choice when there is a lack of response or worsening trends during nonspecific renoprotective treatment (feeding an appropriate diet, administering drugs to block portions of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system).

Chronic Kidney DiseaseBiopsy in animals with chronic kidney disease in IRIS stage IV or late stage III is usually unrewarding and generally should be avoided. Nonetheless, a potential reason to perform a biopsy in an animal with chronic kidney disease is juvenile-onset nephropathy. In some cases, definitive diagnosis of the changes present (or the likelihood that they are attributable to an inherited defect) is sufficiently important to justify biopsy.

Although the pathologic findings rarely affect therapy directly (because the more frequent types of congenital or inherited renal disease do not have effective treatments), biopsy-derived information can influence breeding decisions for related animals and contribute to a more informed prognosis than might otherwise be available.

ContraindicationsRegardless of the indications for a renal biopsy, one should not be performed (or should at least be delayed until the patient’s condition is stabilized) if it cannot be done safely. The main complication of clinical concern is life-threatening hemorrhage. Factors associated with increased risk for this complication are small patient size (small size of the biopsy target relative to adjacent large vessels), especially weight less than 5 kg, and disordered hemostasis (eg, thrombocytopenia, prolonged bleeding time) or uncontrolled hypertension.

Other relative or absolute contraindications to renal biopsy include infection, especially abscesses or localized infections that might be pierced or disseminated by the biopsy; large renal cysts; inadequate control of patient pain or motion (including breathing); and inadequate operator competence.TimingAnimals with acute nephritis or nephrosis, as well as those with acute nephritic glomerular disease, generally should have a biopsy performed as soon as they are stabilized. Animals with nephrotic glomerular diseases usually do not need a biopsy performed as urgently as animals with nephritic conditions, and they sometimes must have fluid accumulations, especially ascites, reduced before the biopsy is performed.

For animals with subclinical renal proteinuria, the timing of biopsy requires clinical judgment. The decision should be guided by verifying proteinuria is persistent and then by magnitude and rate of change of proteinuria and any associated azotemia. In animals with juvenile-onset nephro-pathies, a renal biopsy can be performed during anesthetic episodes or surgery for other reasons (eg, castration or ovariohysterectomy). Renal biopsy also may be indicated during exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy procedures.