Rabies Exposure in Humans & Pets

J. Scott Weese, DVM, DVSc, DACVIM, FCAHS, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada

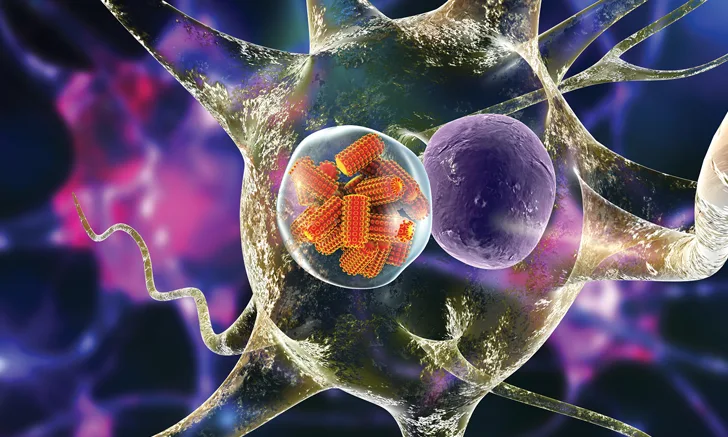

Illustration of rabies virus in a neuron

Rabies virus infections in humans are nearly always fatal but are almost completely preventable with appropriate postexposure prophylaxis (PEP). Proper management of rabies exposure is therefore critical.

Rabies virus is a zoonotic Lyssavirus and accounts for substantial mortality rates internationally in both humans and animals. Rabies is estimated to kill 50 000 humans per year,1 although this is concentrated in developing countries with endemic canine rabies and often inadequate public education and health systems. Canine variant rabies is not present in the United States, but some risk is still present because of spillover of other rabies virus variants from wildlife reservoirs (eg, skunks, bats, raccoons, foxes) into domestic animals. (See Resource.)

Rabies is rarely identified in domestic dogs in the United States, with only 67 cases reported in 2015.2 The disease incidence is higher in cats, with 244 US cases reported in 2015.2 However, because rabies virus is endemic in wildlife reservoirs throughout North America and much of the world, some potential for rabies exposure in humans and domestic animals always is present.

Key Communication Points

Rabies vaccination of dogs, cats, and ferrets does not impact quarantine of an animal that has bitten a human but can have a major influence on the approach to an animal that has been bitten.

The potentially significant consequences of rabies exposure to an unvaccinated animal must not be ignored; in the author’s experience, euthanasia of unvaccinated dogs in lieu of quarantine presumably kills many more dogs in North America than rabies.

What Constitutes Rabies Exposure?

Confusion often exists when responding to a potential rabies exposure case. Understanding what constitutes exposure and the ideal protocol when managing exposure is critical to facilitating an appropriate response and calming concerns.

Rabies virus must be inoculated into the body for infection to occur. Inoculation typically occurs via bites from animals in late stages of rabies infection, when they are shedding large amounts of rabies virus in saliva. Scratches are a potential exposure risk if rabies virus has been previously deposited on the skin via saliva and the scratch inoculates the wound, or if saliva is on the paw and the animal then scratches a human or another animal. The approach to managing scratch cases varies by region and should be decided on a case-by-case basis. Direct contact of rabies virus with mucous membranes (eg, saliva or neurologic tissue contact with the nose, mouth, or eyes) also poses a transmission risk.

Rabies virus is shed in the late stages of infection, as infected patients capable of transmitting rabies virus develop clinical signs and die within a short period of time. This results in a relatively short observation period (ie, usually 10 days) to determine whether an animal that has bitten another individual may have been shedding rabies virus at the time of the bite.

Any potential rabies exposure should be assessed by healthcare and public health professionals to determine the best response.

Rabies Exposure in a Pet

Management of potential rabies exposure in a pet is designed to reduce the risk to both animals and humans. The 2 priorities to address first are the vaccination status of the bitten animal and whether the biting animal is available for observation or testing. Appropriate response is determined based on the regulations in the jurisdiction where the bite ocurred and the specific scenario of each incident. Responses can include vaccination, observation, quarantine, and, in some cases, euthanasia.

In some areas, risk assessment can determine the appropriate response to rabies exposure in an unvaccinated domestic animal, depending on the likelihood of exposure based on the nature of the bite and rabies virus patterns and epidemiology in the area. In regions where the canine rabies virus variant is not present (eg, United States, Canada), dog-to-dog transmission of rabies is rare and most rabid domestic animals are infected by wildlife. For example, a bite to a pet dog from another pet dog that cannot be traced (eg, a roaming dog that bites another dog in a dog park), with no evidence of abnormal behavior, in a region with a very low incidence of rabies in domestic animals and wildlife, may be deemed a low enough risk that specific measures are not taken.

Guidelines for rabies exposure are not absolute, and specific responses may vary between or even within regions. Recommended observation or quarantine periods may vary. For example, in Ontario, Canada, observation periods are no longer recommended for vaccinated animals that are exposed but receive a booster vaccine within 7 days.3 In Texas, exposed and unvaccinated animals must be vaccinated immediately, confined for 90 days, and given booster vaccines on weeks 3 and 8.4 Familiarity with the regulations and recommendations related to rabies exposure in the specific practice area is important.

Rabies Exposure in a Human

Exposure by a Pet Dog, Cat, or Ferret

Management of potential rabies exposure in humans focuses on determining if there is a reasonable concern that the biting animal was shedding rabies virus.5 Although rabies vaccination is highly effective in animals, there is no guarantee that a vaccinated animal does not have rabies. Therefore, the animal’s vaccination status has no impact on the response to an animal biting a person.

The focus of response is instead on determining whether the animal might be rabid. The pet dog, cat, or ferret is ideally observed for 10 days because, if the animal is still alive and neurologically normal at the end of this period, he or she could not have been shedding rabies virus at the time of the bite. (See Table 1.)

Table 1: Common Responses to Rabies Exposure in Humansa

a Decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis by local public health or medical personnel.

The alternate approach involves testing (ie, euthanasia and brain analysis) that is typically undesirable. This alternative is best reserved for situations in which it is unsafe or inhumane to keep a biting animal alive for the observation period, when observation is otherwise difficult to perform, or if the animal shows signs of rabies at the time of the bite.

Exposure by Wildlife

In situations in which the biting animal is a rabies-reservoir species (eg, fox, skunk, bat, raccoon, mongoose), the bitten individual should seek medical and public health consultation and receive PEP. If the biting wildlife is available for testing, PEP can usually be delayed pending results. If the wildlife is unavailable, the individual should receive PEP right away.

Bites from non-rabies-reservoir species (eg, rats, squirrels, otters) should be assessed on a case-by-case basis (see Table 1), considering the circumstances of the bite (eg, the animal’s behavior preceding the bite) and the epidemiology of rabies in that species and geographic region.