Parasite Risk in Dog Parks

Donato Traversa, DVM, PhD, DipEVPC, EBVS, University of Teramo, Teramo, Italy

In the Literature

Stafford K, Kollasch TM, Duncan KT, et al. Detection of gastrointestinal parasitism at recreational canine sites in the USA: the DOGPARCS study. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13(1):275.

The Research …

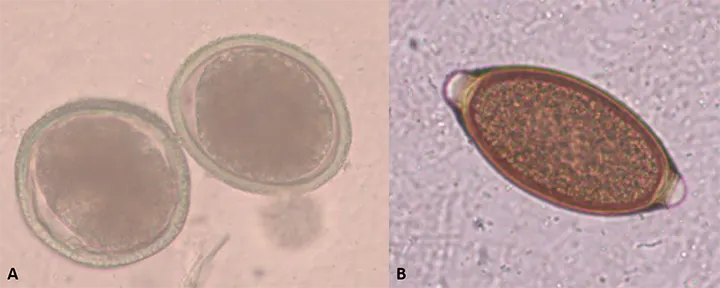

Canine intestinal parasites are found worldwide. Most dogs become affected by ingesting infective agents (eg, Toxocara canis [ie, roundworm] or Trichuris vulpis [ie, whipworm] eggs [Figure], Giardia duodenalis cysts, ancylostomatid third-stage larvae [ie, hookworm]) in a contaminated environment. These can cause intestinal disease and, in some cases (eg, T canis, Ancylostoma spp, some G duodenalis genotypes), pose a relevant hazard to human health.1-3

Common misconceptions can lead to undiagnosed parasite infections, including pet owner belief that lifestyle can prevent infection and only puppies are at risk for intestinal parasites, especially worms. Intestinal parasites infect dogs irrespective of age and lifestyle and may potentially cause severe clinical signs (even in adult dogs); however, their clinical relevance is often underestimated.1,2

Undetected infections may become clinically apparent, and untreated dogs may shed parasites that contaminate the environment, presenting a threat to animals and humans. One Health indicates that routine monitoring and appropriate parasiticide treatments are crucial for dogs.

Off-leash dog parks are increasingly available, as they provide dogs the opportunity for play, exercise, and socialization; however, these parks may serve as a source of parasites. This study* evaluated the occurrence of intestinal parasites in dogs visiting these parks. The relationship between positivity to intestinal parasites and use of heartworm/intestinal parasite preventives was also investigated, as well as the complementary efficiency of 2 diagnostic methods to detect intestinal parasites: a validated coproantigen immunoassay and zinc sulfate centrifugal flotation (CF).

Samples were taken from 3,006 dogs visiting 288 dog parks. Stool samples were examined with conventional zinc sulfate CF and coproantigen assays able to detect Giardia spp and intestinal nematodes. At least one parasite was found in 20.7% of dogs in 85.1% of parks. Giardia spp were the most commonly detected protozoan, and hookworms were the most commonly diagnosed nematode. Combined use of CF and a coproantigen assay allowed detection of 78.4% more nematode infections than with CF alone.

Hookworms and whipworms were found in dogs of all ages, but roundworms were found only in dogs <4 years of age. Overall, 42% of dogs <1 year of age were infected by Giardia spp or nematodes. A significantly lower number of dogs receiving preventive medication tested positive for intestinal nematodes.

Toxocara canis (A) and Trichuris vulpis (B) unembryonated eggs. These eggs need some weeks in the environment to become infective.

… The Takeaways

Key pearls to put into practice:

Intestinal parasites may be a constant threat in dogs; routine testing and treatment may be needed.

It is crucial to educate owners that, although dog parks play an important role in the well-being of their pet, there is an increased risk for exposure to intestinal parasites.

Frequent fecal examination with appropriate and combined diagnostic techniques is important in dogs of all ages.

Dogs should be maintained on broad-spectrum parasiticides used on an individual basis and according to local epizootiology conditions. It is recommended that recognized guidelines be followed (see Suggested Reading) to safeguard patient health, minimize the risk for humans, and reduce environmental contamination.

*This study received funding from Elanco Animal Health. Testing was provided by IDEXX.

You are reading 2-Minute Takeaways, a research summary resource presented by Clinician’s Brief. Clinician’s Brief does not conduct primary research.