Is This Pancreatitis?

A 4-kg 8-year-old spayed female domestic long hair cat was referred with a 4-day history of lethargy, anorexia, and vomiting.History. The cat lives with another cat that does not manifest any systemic abnormalities. She was presented to the primary veterinarian 2 weeks earlier for lethargy and 1 episode of vomiting, but a diagnosis was not determined.

Physical Examination. Physical examination revealed splinting of the abdomen and drooling upon abdominal palpation. The cat was mildly dehydrated and had an unkempt hair coat.

Diagnostics. Complete blood count showed neutrophilia and nonregenerative anemia. Serum biochemical profile revealed elevated liver enzymes (ALT, ALP), azotemia, elevated protein, and mild hyperglycemia (Table). Tests for FeLV and FIV were negative. Abdominal radiographs were normal.

ASK YOURSELF...

What conditions might fit these nonspecific signs? How would you begin to differentiate?

Describe all possible clinical signs of feline pancreatitis. How does it differ from pancreatitis in dogs?

What diagnostic tests are most useful when diagnosing pancreatitis in cats?

What is the difference between acute pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis?

Diagnosis: Pancreatitis

Diagnosing pancreatitis in cats can be frustrating due to lack of specific and overt clinical signs. The combined use of often-subtle history and physical examination findings, routine blood analysis (to rule out other causes), abdominal ultrasound, and ELISA testing specific for feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (fPLI) is the most conclusive way to diagnose the disease.

Thoracic radiography is indicated if dyspnea is present or if the cat presents with evidence of concurrent thoracic disease; outdoor cats should be screened for intestinal parasites and Toxoplasma gondii. Additional tests may include ultrasound-guided needle aspiration or laparoscopy with pancreatic biopsy. Other possibilities for cats include hypercalcemia and organophosphates. Hyperlipidemia has been associated with pancreatitis in humans and has been suggested in dogs but not in cats.1

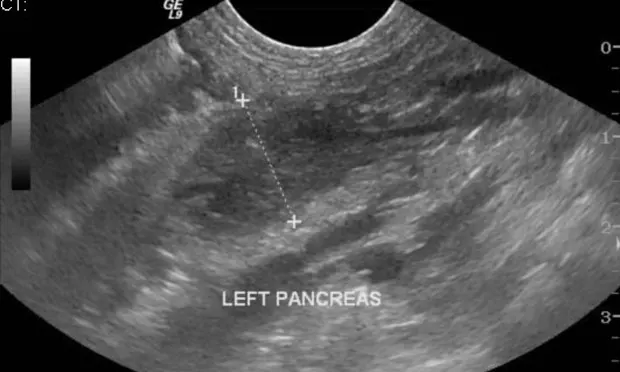

In this case, the abdominal ultrasound showed pancreatic enlargement and hyperechoic mesenteric fat as well as mild peritoneal effusion (Figure 1). Serum fPLI concentration was increased.

Figure 1. Abdominal ultrasound showing pancreatic enlargement, a hypoechoic pancreas, and a hyperechoic mesenteric fat. The pancreas is abnormally thick at 1.46 cm (previous studies have reported the measurement of a normal feline pancreas to be under 1 cm).7

Pancreatitis. Both acute and chronic pancreatitis can be mild or severe, but most acute cases tend to be severe and chronic cases are often mild. Acute pancreatitis is generally reversible and is characterized by edema, hemorrhage, and the absence of fibrosis. Neutrophilic infiltration, peripancreatic fat necrosis, and pancreatic acinar cell necrosis have been documented (Figure 2).2 Hypocalcemia occurs in pancreatitis although the pathogenesis remains unclear. Severe hypocalcemia is associated with a poor prognosis.

Figure 2. Histologic example of acute pancreatitis showing neutrophilic infiltration (small square on left), hemorrhage (large rectangle on right), and pancreatic necrosis (arrow).

Chronic pancreatitis may wax and wane for months and may be more difficult to diagnose, as leakage of enzymes is often not high enough to be detected by diagnostic tests or assays. Long-term inflammation of the pancreas is associated with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. The hallmarks of irreversible chronic pancreatitis are fibrosis and acinar atrophy.2 Chronic pancreatitis is often associated with inflammatory bowel disease and these patients may develop decreased serum concentrations of cobalamin, which may require supplementation.

Treatment.Supportive treatment addresses clinical signs and nutritional support is paramount to recovery. While treatment is supportive in both species, dogs can tolerate longer periods of starvation. Cats need nutritional support to stave off hepatic lipidosis (if it is not already present).1,3,4 In addition, continual fasting may blunt villous epithelium in the intestine and promote bacterial translocation; therefore early enteral support is indicated.

Historically cats had been given diazepam to stimulate appetite but it should not be considered in feline pancreatitis patients due to a reported case of hepatic necrosis. Empirically, foods given to pancreatitis patients should be highly digestible and contain only low to moderate amounts of fat to decrease pancreatic secretions as well as higher levels of carbohydrates as a calorie source.

Central acting antiemetics for control of nausea and vomiting are essential to recovery, allowing prompt oral feeding. Pain control is important even if the cat does not show observable signs of pain.5 Antibiotics are not indicated unless there is evidence of infection.

For this cat, intravenous lactated Ringer's solution was administered to correct dehydration and to provide daily fluid requirements. Dolasetron (0.3 mg/kg SC Q 24 H), metoclopramide (1 mg/kg/day CRI) and buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg IM Q 6 H) were administered.

Outcome. On the third day of hospitalization tube feeding was considered but the cat ate tuna after being syringe-fed; she continued to eat on her own.

DID YOU ANSWER...

Esophagitis, gastritis, hepatopathy, nephropathy, neoplasia, gastric ulceration, infectious disease, gastrointestinal or urinary obstruction, and toxins. These can be differentiated by performing a complete blood count, serum biochemical profile, and abdominal radiography.

Anorexia, lethargy, dehydration, hypothermia, vomiting, abdominal pain, dyspnea, diarrhea, and ataxia. In cats, vomiting occurs less frequently and abdominal pain is more difficult to discern.

Serum fPLI concentration and abdominal ultrasound are the most useful tools in diagnosing feline pancreatitis.5,6

Acute pancreatitis tends to be more severe while chronic disease is often mild.

Tx at a Glance

Nutritional support

Isotonic intravenous fluid therapy

Antiemetics

Pain control

Antibiotics if evidence of complicating infection