The Pain Management Pipeline

Translational medicine remains a great challenge in the field of pain management. For many reasons, it has proven exceedingly difficult to go from bench research that identifies new targets in the nociceptive signaling mechanisms and pathways to a novel drug that safely and effectively addresses that target. Most advances in pain pharmacology are new drugs of an existing class or novel adaptations of drug classes approved for alternate uses derived from astute clinical (and off-label) observations.1

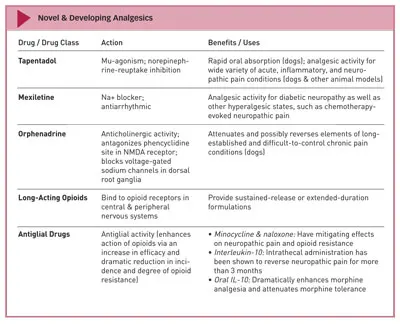

There are several pharmacologic developments that may be able to address acute and chronic pain circumstances and syndromes. This article will provide information about several of these, with the disclaimer that few or no reports in the literature address their pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, toxicity, and evidence on clinical use or utility in dogs or cats. Nevertheless, they are pharmacologic interventions to watch carefully because they do hold promise for future use in veterinary medicine.

TAPENTADOLMost practitioners have used tramadol. In humans, about 40% of the analgesic effect of this increasingly popular drug is derived from a mu-agonist effect, although it requires metabolism to the active M1 metabolite. Another 40% of the effect in humans is serotoninergic and 20% is noradrenergic; both effects are an enhancement of inhibitory neurotransmitters.

Pharmacokinetic studies in dogs, however, reveal that this agent produces almost undetectable amounts of the M1 metabolite and that the half-life of the drug is about one third of that in humans (only 1.7 hours). This finding suggests that administration Q 6 H might be needed to achieve the desired (or at least maximum) effect.2

There are several pharmacologic developments that may be able to address acute and chronic pain circumstances and syndromes in veterinary patients.

However, tapentadol (Nucynta, ortho-mcneil.com) is the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved centrally acting analgesic drug for moderate to severe pain in adults in 25 years, and it appears to overcome both of these issues. It is the parent molecule, not a metabolite, that has both mu-agonism and norepinephrine-reuptake inhibition. In humans, the drug appears to have potency between that of tramadol and that of morphine, and serum levels are satisfactory when given both intravenously and orally.3

In preclinical trials, tapentadol exhibited rapid oral absorption in dogs and also showed analgesic activity for a wide variety of acute, inflammatory, and neuropathic pain conditions in dogs and other animal models.4 It appears to have a half-life of almost 4 hours in dogs, but the bioavailability is lower in this species than in humans. Tapentadol is metabolized mostly by glucuronidation5 and thus may not be a drug to consider for cats. If the clinical pharmacodynamic profile proves to be as promising in dogs as in humans, tapentadol may be a valuable addition to the veterinary formulary.

MEXILETINEMexiletine (Mexitil, boehringer-ingelheim.com) is an oral Na+ blocker used as an antiarrhythmic agent, and as such it is sometimes called oral lidocaine. It is licensed as a class 1B antiarrhythmic agent but has also been used for diabetic neuropathy,6 a classic neuropathic pain state in humans. Rodent models and human anecdotes exist for other hyperalgesic states, such as chemotherapy-evoked neuropathic pain.7

ORPHENADRINEOrphenadrine (various trade names), a derivative of diphenhydramine, is indicated for the treatment of painful musculoskeletal conditions but is used in a wide variety of chronic or remitting pain conditions, such as muscle spasms associated with Parkinson disease, sciatica, radiculopathy, and headache syndromes.

It has anticholinergic activity but from an antinociceptive standpoint, is known to antagonize the phencyclidine site within the N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor8 (as do ketamine and amantadine). It also blocks the voltage-gated sodium channels in the dorsal root ganglia.9 The NMDA receptor is a calcium channel on the postsynaptic second-order neuron that, when activated and opened by intense or sustained presence of excitatory amino acids, becomes crucial to the establishment of the chronic and maladaptive pain state.

Orphenadrine holds the promise to attenuate and possibly reverse elements of long-established and difficult-to-control chronic pain conditions in dogs.

LONG-ACTING OPIOIDSThe analgesic effects and benefits of opioids are well understood and accepted for a wide variety of acute and chronic pain conditions, and technologies are being explored for sustained-release or extended-duration formulations; at least 1 compounded version is commercially available for use in dogs and cats, although it is not an FDA-approved product (buprenorphine SR, zoopharm.net). Other long-acting opioid compounds, formulations, and delivery mechanisms are in development for use in dogs during the perioperative period.

As the use of strong opioids becomes more prevalent in veterinary medicine, veterinarians should be aware of peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists that have been developed to minimize the adverse effects of opioids. These agents permit the central analgesic effect of the opioid but block their peripheral effect:

Alvimopan (Entereg, adolor.com/gsk.com) is an oral preparation used to prevent postoperative ileus from parental opioids.10

Methylnaltrexone (Relistor, wyeth.com/progenics.com) is administered SC to treat and prevent constipation.11

ANTIGLIAL DRUGSHistorically, spinal cord glial cells have been considered to have supporting roles (eg, astrocytes providing “architecture” and microglia acting as local macrophages). However, these cells are now known to be highly neurohormonally active; they interact with, yet remain outside, the traditional nociceptive pathways. Glial cells are involved in creating and sustaining the painful state, and they inhibit the action of opioids, all while actually being activated by opioids.12 Researchers note that in the future, it is likely that opioids will be taken with a glial inhibitor to enhance the action of the opioid via an up to 8-fold increase in efficacy and a dramatic reduction in the incidence and degree of opioid resistance.13

It is important to note that recommending the use of these drugs in dogs and cats would be premature until additional data on their safe and effective use in both species are available. Minocycline and the + enantiomer of naloxone (it is the – enantiomer that binds to mu receptors on neurons) have demonstrable antiglial activity and have mitigating effects on neuropathic pain and opioid resistance.14,15 However, a compound perhaps receiving the most interest for its antiglial activity is interleukin (IL)-10. Receptors for IL-10 exist on glia but not on neurons, and when bound by IL-10 they return activated glia to basal activity. An intrathecal administration of IL-10 has been shown to reverse neuropathic pain for more than 3 months.16

An exciting development is the oral form of the drug, under the investigational names AV411 and MN166. The agent is licensed for use in Japan under the name ibudilast (avigen.com) as a non-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitor for asthma and poststroke dizziness. It is also under investigation as a treatment for multiple sclerosis.

Thus, it has an established human safety profile; this means that the path to FDA approval may be much faster than new drugs to market typically experience. At least 2 phase I trials are already underway, and both trials have shown that AV411 is active as a glial inhibitor with oral administration, crosses the blood–brain barrier, effectively reduces glial activation, dramatically enhances morphine analgesia, and attenuates morphine tolerance and withdrawal.17

CONCLUSIONIt is important to note that recommending the use of these drugs in dogs and cats would be premature until additional data on their safe and effective use in both species are available. However, being alert to compelling developments such as these is wise, and it is always helpful to know about the potential application of these and other emerging pain management modalities to veterinary patients. The field is rapidly growing and changing—it is a most exciting time to be a “pain-aware” practitioner.

THE PAIN MANAGEMENT PIPELINE: PHARMACOLOGIC DEVELOPMENTS TO WATCH • Mark E. Epstein

References1. Do animal models tell us about human pain? Lascelles BDX, Flecknell PA. IASP Pain Clinical Updates XVIII: 2010.2. Pharmacokinetics of tramadol and the metabolite O-desmethlytramadol in dogs. Kukanich B, Papich MG. J Vet Pharmacol Therap 27:239-246, 2004.

Tapentadol hydrochloride: A centrally acting oral analgesic. Wade WE, Spruill WJ. Clin Ther 31:2804-2818, 2009.4. Tapentadol hydrochloride. Tschentke TM, de Vry J, Terlinden R, et al. Drugs Fut 31:1053, 2006.

Tapentadol. US Food and Drug Administration new drug application. Available at: accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2008/022304s000_PharmR_P2.pdf.6. Mexiletine. A review of its therapeutic use in painful diabetic neuropathy. Jarvis B, Coukell AJ. Drugs 56:691-707, 1998.7. Mexiletine reverses oxaliplatin-induced neuropathic pain in rats. Egashira N, Hirakawa S, Kawashiri T, et al. J Pharmacol Sci 112:473-476, 2010.8. Orphenadrine is an uncompetitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist: Binding and patch clamp studies. Kornhuber J, Parsons CG, Hartmann S, et al. J Neural Transm Gen Sect 102:237-246, 1995.

Involvement of voltage-gated sodium channels blockade in the analgesic effects of orphenadrine. Desaphy JF, Dipalma A, De Bellis M, et al. Pain 142:225-235, 2009.10. Peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists and postoperative ileus: Mechanisms of action and clinical applicability. Viscusi ER, Gan TJ, Leslie JB, et al. Anesth Analg 108:1811-1822, 2009.

Methylnaltrexone treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with advanced illness. Chamberlain BH, Cross K, Winston JL, et al. J Pain Symptom Manage 38:683-690, 2009.12. The role of glia and the immune system in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain. Vallejo R, Tilley DM, Vogel L, et al. Pain Pract 10:167-184, 2010.

Immune and Glial Regulation of Pain. DeLeo JA, Sorkin LS, Watkins LR—Seattle, Washington: International Association for the Study of Pain, 2007.14. Non-stereoselective reversal of neuropathic pain by naloxone and naltrexone: Involvement of toll-like receptor (TLR4). Hutchinson MR, Zhang Y, Brown K, et al. Eur J Neurosci 28:20-29, 2008.15. Minocycline suppresses morphine-induced respiratory suppression, morphine-induced reward, and enhances systemic morphine-induced analgesia. Hutchingson MR, Northcutt AL, Chao LW, et al. Brain Behav Immun 22:1248-1256, 2008.16. Release of plasmid DNA-encoding IL-10 from PLGA microparticles facilitates long-term reversal of neuropathic pain following a single intrathecal administration. Soderquist RG, Sloane EM, Loram LC, et al. Pharm Res 27:841-854, 2010.17. Modulation of microglia can attenuate neuropathic pain symptoms and enhance morphine effectiveness. Mika J. Pharmacol Rep 60:297-307, 2008.