Managing Melting Ulcers in Dogs

Georgina M. Newbold, DVM, DACVO, The Ohio State University

In the Literature

Tsvetanova A, Powell RM, Tsvetanov KA, Smith KM, Gould DJ. Melting corneal ulcers (keratomalacia) in dogs: a 5-year clinical and microbiological study (2014-2018). Vet Ophthalmol. 2021;24(3):265-278.

The Research …

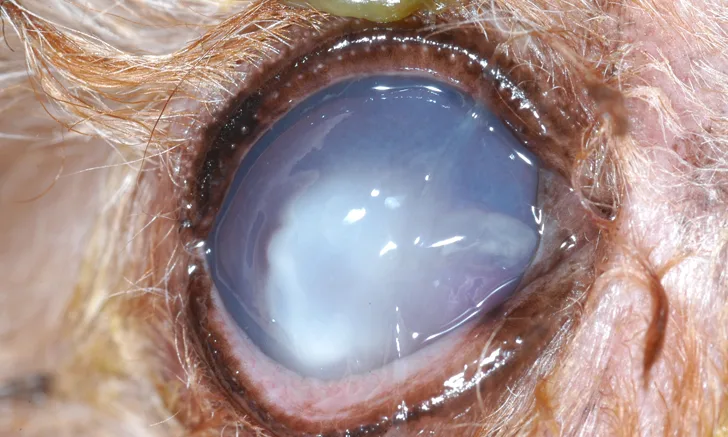

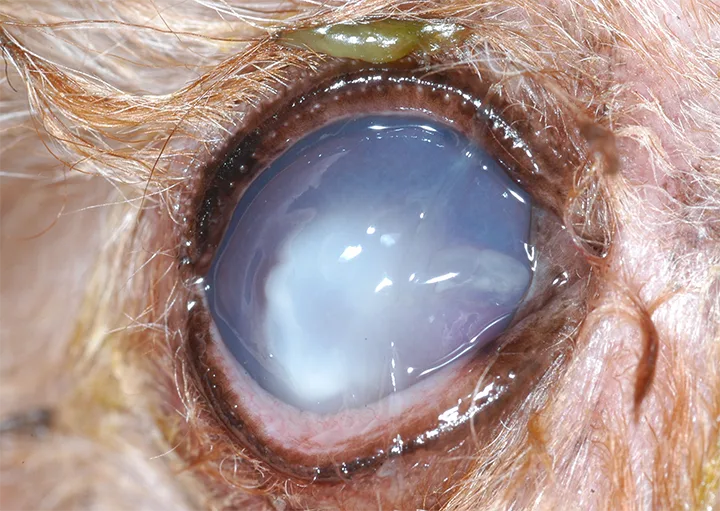

Keratomalacia (ie, corneal melting) is a complex ocular surface disease that can rapidly lead to loss of vision or rupture of the eye. Brachycephalic dog breeds and dogs with dry eye are at higher risk for developing melting corneal ulcers.1-3 This condition often begins with a superficial corneal wound that becomes infected, triggering a cascade of enzymatic destruction. Protease and collagenase enzymes produced by bacteria and local inflammatory cells can quickly digest the corneal tissue, leading to melting of the corneal stroma (Figure).1

This retrospective study sought to identify the bacteria and antimicrobial susceptibility profile associated with melting corneal ulcers in dogs. Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa and gram-positive beta-hemolytic Streptococcus spp were the predominant cultured organisms from 110 melting corneal ulcers in 106 dogs. Bacterial susceptibility testing found these isolates to have different antibiotic sensitivity patterns.

P aeruginosa showed sensitivity to gentamicin and fluoroquinolones. Beta-hemolytic Streptococcus spp were most sensitive to amoxicillin/clavulanate, cephalexin, and clindamycin, followed by doxycycline and chloramphenicol; some resistance to fluoroquinolones was noted.

All bacterial isolates grouped together showed the highest sensitivity to fluoroquinolones. Results of a recent study showed similar bacterial isolates (eg, Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, beta-hemolytic Streptococcus spp, P aeruginosa) from canine corneal ulcers and minimal resistance to fluoroquinolones.3

Medical management of melting ulcers is successful in 55% to 80% of patients that receive aggressive treatment, but referral for surgical management may be required in some dogs.1,2,4 Geographic variation and initial antibiotic selection may influence the corneal bacterial population. Prompt diagnosis and an intensive treatment plan can help provide a successful outcome in patients with melting ulcers.

Infected melting corneal ulcer in a wirehaired dachshund

… The Takeaways

Key pearls to put into practice:

Corneal cytology combined with culture and susceptibility testing is recommended in all patients with deep or melting ulcers. In-clinic cytology can help direct initial antibiotic therapy.

Multimodal topical antibiotic therapy with a combination of both gram-positive and gram-negative activity may help improve the spectrum of antimicrobial coverage. Potential combinations include tobramycin/cefazolin, gentamicin/chloramphenicol, and ciprofloxacin/cefazolin. Alternatively, monotherapy with a second-generation fluoroquinolone may be sufficient in many cases pending culture and susceptibility testing.

Anticollagenase therapy (eg, topical serum or plasma) and oral doxycycline may help slow progression of keratomalacia.

Frequent, rigorous (eg, every 2 hours during waking hours and every 4 hours overnight) topical medication application is important to manage melting ulcers. Daily or frequent recheck examinations can help determine whether surgical stabilization is necessary. Referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist early in the course of disease may improve the long-term outcome.

You are reading 2-Minute Takeaways, a research summary resource presented by Clinician’s Brief. Clinician’s Brief does not conduct primary research.