Lyme Disease in Dogs

Craig Datz, DVM, MS, DABVP (Canine & Feline, Feline), DACVIM (Nutrition), University of Missouri

Overview

Lyme disease (ie, Lyme borreliosis), a bacterial infection that occurs primarily in dogs and humans, is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi transmitted by ticks. Musculoskeletal joints are commonly affected. Kidney disease (Lyme nephritis) has been reported as a rare clinical manifestation.1

Epidemiology

Geographic Distribution

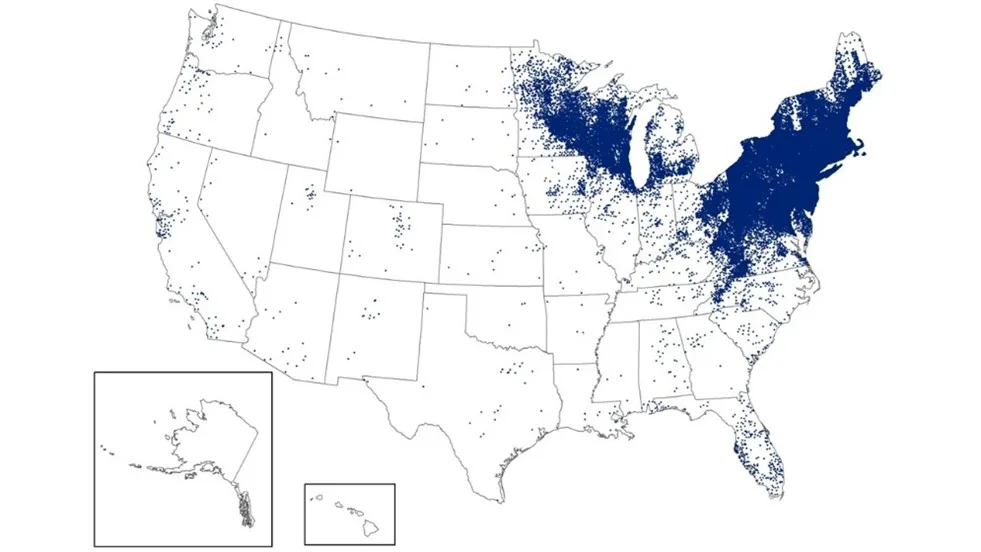

In the United States, distribution in dogs is the same as in humans, with the majority occurring in the northeast and upper Midwest, with a continually increasing range (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 Map of the United States showing reported human cases of Lyme disease in 2023. Each dot in the county of residence represents a reported case.34

Incidence/Prevalence

Up to 90% of dogs in endemic areas may be exposed to B burgdorferi.2

Historic average canine seropositive rates in the United States range from 5.1% to 7.2%, with the highest average prevalence in New England (12.3%).3

Annual canine seropositive results compiled by the Companion Animal Parasite Council in 2024 indicated a 4.32% prevalence in the United States.4

Signalment

Species

Clinical disease is found in dogs and occasionally other domestic animals (eg, horses, cows).

Cats may be exposed, but natural disease has not been broadly recognized.5-7

Breed Predisposition

Any dog exposed to B burgdorferi may become infected.

Labrador retrievers and golden retrievers may have a higher prevalence for Lyme nephritis than other breeds,8,9 although Lyme seropositivity was not associated with microalbuminuria in subclinical retrievers in another survey.10

Age

Dogs of any age may be infected after natural exposure.2

Dogs 2 to 9 months of age were more likely to develop disease experimentally.2

Experimental infection of adult dogs with B burgdorferi did not cause clinical signs.2

Sex

No sex predisposition has been reported.

Genetic Implications

Genetic associations with Lyme disease have not been reported in dogs.

There is some clinical speculation for predisposition in Bernese mountain dogs to Lyme borreliosis, but there is no definitive association.11-13

Causes & Risk Factors

B burgdorferi is transmitted by Ixodes spp ticks, primarily Ixodes scapularis in the northeastern and midwestern regions and Ixodes pacificus in the western region of the United States.2

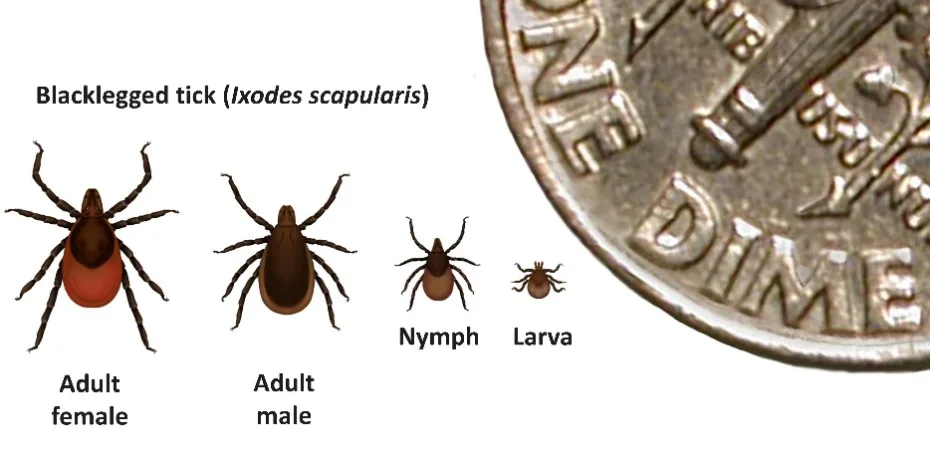

Tick larvae and nymphs feed on small mammals, and adult ticks feed on deer and larger mammals (Figure 2).14

Infected nymphs are the main vectors of transmission.15

Studies suggest B burgdorferi is transmitted only after 36 to 48 hours of attachment; therefore, a small, flat, nonengorged Ixodes spp tick on a dog carries a very low risk of infection (Figure 3).14,16

Potential risk factors include tick exposure, time spent outdoors, and living in or traveling to forested or wooded habitats.2,9,17-19

FIGURE 2 Black-legged ticks have a 2- to 3-year life cycle and undergo 4 life stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult.

FIGURE 3 Adult ticks are approximately the size of a sesame seed; nymphs are approximately the size of a poppy seed.

Pathophysiology

Bacteria proliferate locally in the skin at the site of tick attachment (although skin lesions are rarely observed in dogs), then spread and may localize in joints, connective tissues, the nervous system, kidneys, and other organs. Innate and adaptive immune responses lead to the production of proinflammatory cytokines and antibodies, but B burgdorferi may evade host immunity and persist extracellularly in tissues. Clinical disease is primarily a result of the immune response.2

History

Pet owners may report decreased appetite, lethargy, and lameness in affected dogs.

Clinical Presentation

Common signs include fever (103°F-105°F [39.4°C-40.6°C]), intermittent or shifting-leg lameness, joint swelling, and lymph node enlargement.

Affected dogs may not exhibit clinical signs.

Some dogs may display mild to moderate limb and/or joint discomfort and pain on palpation.

A positive Borrelia burgdorferi antibody test may be an incidental finding. Discover current recommendations for treating and monitoring dogs that are seropositive but lack clinical signs of Lyme disease in this article on Borrelia burgdorferi Seropositivity in a Clinically Normal Dog.

Differential Diagnosis

Lameness may result from other causes of arthritis, including bacterial (septic) or immune-mediated polyarthritis, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, degenerative joint disease, or other tick-borne disease (eg, ehrlichiosis, anaplasmosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever).

Trauma (eg, sprain, strain) and neurologic problems (eg, intervertebral disk disease) often cause lameness.

Painful limbs and joints have a broad differential list, including myositis, panosteitis, neoplasia, osteomyelitis, hypertrophic osteodystrophy, and hypertrophic osteopathy.

Ixodes spp ticks may be coinfected with other organisms (eg, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia microti), which can complicate diagnosis and management.2

Diagnostics & Diagnostic Findings

Laboratory Findings & Imaging

In experimental and clinical cases, routine blood work (eg, CBC, serum chemistry profile) is generally normal, unless the patient has Lyme nephritis.24

Urine may be collected for analysis, especially to screen for proteinuria; however, proteinuria alone is not diagnostic for Lyme nephritis.2

Radiographs of affected joints may reveal nonerosive polyarthritis, and fluid analysis of joint effusions typically shows nonspecific neutrophilic inflammation.2

Definitive Diagnosis

Microscopy, culture, and PCR are low-yield procedures for direct identification of B burgdorferi organisms and rarely performed.

In research studies, PCR testing has been positive on skin or synovial membrane specimens, but there are no standardized techniques.2

Serology is the most common diagnostic method.

Antibodies to various proteins associated with B burgdorferi can be detected via ELISA, indirect immunofluorescence assay, and Western blot testing.

Currently available serologic tests do not diagnose Lyme disease. Positive results only indicate exposure and seroreactivity, and serology cannot be recommended as an accurate indicator of disease status or response to treatment.2,25

Most assays for B burgdorferi antibodies are specific for exposure and can differentiate between vaccine-induced responses and tick-borne infection.25

Postmortem Findings

Lyme disease is a nonfatal infectious disease, with the possible exception of Lyme nephritis.

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, tubular necrosis and regeneration, and diffuse interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation have been reported in suspected cases of Lyme nephritis.2

Treatment

Inpatient or Outpatient

Uncomplicated cases of Lyme disease are managed on an outpatient basis.

Dogs with suspected Lyme nephritis may need in-hospital treatment.

Medical

The drug of choice for dogs with clinical signs of Lyme disease and supportive diagnostics is doxycycline (10 mg/kg PO every 12-24 hours).2,26

Doxycycline can also be used for treatment of certain other infections (eg Anaplasma spp, Ehrlichia spp, Leptospira spp) and may have anti-inflammatory effects.2,25

Amoxicillin (20 mg/kg PO every 8-12 hours) can be used as an alternative treatment, especially in very young puppies.2,25

Cephalosporins are recommended when parenteral treatment is needed.2,25

Ceftriaxone (25 mg/kg IV or SC every 24 hours)

Cefotaxime (20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours)

Cefovecin (8 mg/kg SC every 14 days for 2 doses)

Clinical improvement often occurs within 1 to 2 days of starting therapy as lameness and fever rapidly resolve.

The appropriate duration of treatment for affected dogs is unknown, but 30 days is commonly suggested.

Antibiotic therapy is unlikely to clear all B burgdorferi organisms.

Experimental studies have documented (via positive culture, isolation, and PCR) persistence even in treated dogs.27-32

Antibody titers are often positive for weeks to months or may drop initially then rise again after 6 months.2

Vomiting or other GI disturbances are occasionally seen with doxycycline or amoxicillin therapy. Administration with food may reduce this risk.

Lyme nephritis is most often progressive and fatal. Treatment with immunomodulators and supportive care is outside the scope of this review. Further information can be found in the ACVIM Lyme consensus update.25

Activity

Exercise restriction is useful until lameness resolves.

Nutritional Concerns

Dogs may be transiently anorexic, but nutritional support is rarely needed.

Dogs with suspected Lyme nephritis and significant proteinuria may benefit from reduced-protein diets.

Treatment at a Glance

The drug of choice is doxycycline (10 mg/kg PO every 12-24 hours for 30 days).

An alternative option is amoxicillin (20 mg/kg PO every 8-12 hours for 30 days).

Monitoring & Follow-Up

Owners should be advised to watch for improvements in lameness, lethargy, and appetite.

Laboratory results are typically unremarkable in Lyme disease; follow-up testing is therefore usually not necessary.

Lyme serology may be repeated after treatment and clinical resolution; however, antibody titers often remain elevated due to persistence of low levels of organisms and/or immunologic memory.

Previously exposed dogs that continue to test positive do not need additional treatment unless clinical signs or other evidence of Lyme disease recur.

Patients with Lyme nephritis are monitored similarly to dogs with other forms of glomerulonephropathy.

Complications

Exposure to B burgdorferi is typically not associated with clinical signs, and disease complications are rare. The persistence of positive antibody titers complicates interpretation of post-Lyme–disease syndromes in humans and dogs. Coinfections with other tick-borne diseases may explain cases of chronic Lyme disease or failure to respond to treatment.

Prognosis

Both treated and untreated dogs generally recover from B burgdorferi exposure and clinical signs of infection without complications.1 The prognosis for dogs affected with Lyme nephritis is poor, but recoveries have been reported following immunosuppressive and supportive treatment.2

Prevention & Pet Owner Education

Pet Owner Education

Owners should be educated on effective measures to prevent exposure to ticks.

Careful daily examination of the hair coat may reveal ticks, although Ixodes spp are tiny and easy to overlook.

Environmental tick control involves keeping grass and vegetation mowed and constructing tick barriers on property edges.2

Owners should be advised that it is rare for Ixodes spp ticks to be transferred from dogs to humans, although humans and dogs may become infected from the same environment.2

Owners may ask whether antibiotics should be administered if ticks are found on the dog. Because dogs are often exposed but not infected, prophylaxis with antibiotics is not recommended.

Prevention

In addition to avoiding tick exposure and using appropriate acaricides, vaccination may be useful in endemic areas.

Administration of 2 vaccinations 2 to 3 weeks apart is recommended initially.

Lyme vaccines may be combined with other routine canine vaccines; product label instructions for minimum ages should be followed.

Annual revaccination is currently recommended, as long-term immunity studies have not been published.

Vaccination has not been proven to be 100% effective in preventing Lyme disease, and opinions differ on the value of routine vaccination of all dogs.2,25,26

The ACVIM Lyme consensus panel was split on this opinion, with 3 members recommending vaccination and 3 dissenting.25

The value of vaccines in preventing Lyme nephritis is unknown, as some affected dogs likely have a history of vaccination.

Future Considerations

More studies are needed to demonstrate a causal link between B burgdorferi and glomerulonephritis, as well as to investigate genetic predisposition.

Improvements in diagnostic testing for actual organisms instead of antibody response to infection would be useful.

A new diagnostic assay using novel biomarkers and an algorithm has shown promise in humans.33

Vaccination of seropositive dogs is controversial, and prospective challenge studies could help answer questions about vaccine efficacy.

It is important to monitor environmental changes, as tick and host ranges may increase in the future due to changes in climate.