Lower Urinary Tract Signs in an Older Dog

A 9-year-old spayed female miniature schnauzer presented for lower urinary tract signs.

History. The dog had a 2-month history of pollakiuria and stranguria. Free-catch urinalysis done by the referring veterinarian showed hematuria and pyuria. Aerobic bacterial urine culture showed bacterial growth, although the organism was not quantified or identified. Microbial susceptibility showed that the bacteria were susceptible to numerous antibiotics, including amoxicillin and cefadroxil. The dog was treated with oral amoxicillin for 2 weeks.

Clinical signs resolved during antibiotic therapy, but recurred 4 days after amoxicillin was discontinued. The dog was then treated with oral cefadroxil for 2 weeks but again clinical signs returned a few days after antibiotics were discontinued. A second voided urinalysis showed persistent hematuria and pyuria. The owner elected further workup of the problem. Antibiotics were discontinued 5 days before presentation. At the time of presentation, the patient was consuming a complete and balanced, dry commercial maintenance diet.

Physical Examination. The dog weighed 7.2 kg; body condition score was 4 of 5. The urinary bladder felt thickened and contracted. No abnormalities were found on rectal examination or during the remainder of the physical examination.

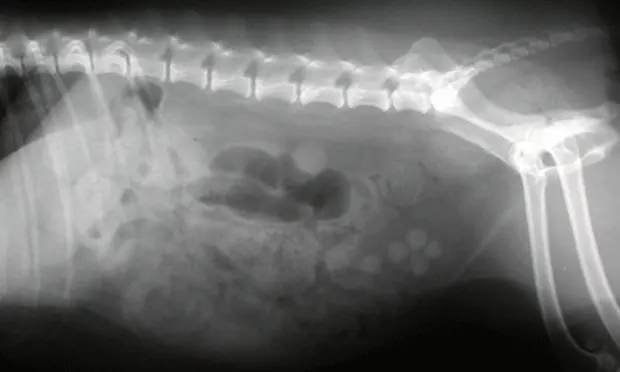

Initial Diagnostic Procedures. Clinical signs of pollakiuria, stranguria, hematuria, and pyuria localized the problem to the lower urinary tract (LUT). The 3 most likely causes for LUT disease in this dog were urinary tract infection (UTI), urolithiasis, and neoplasia. Results of a complete blood count, serum biochemical profile, urinalysis, and urine culture are shown in Table 1. Survey abdominal radiographs were performed (Figure 1, above. Survey lateral abdominal radiograph showing uroliths present in the bladder).

Diagnosis: Urinary tract infection, bladder calculi, and portal systemic shunt

Further Diagnostics. To confirm the mineral composition of the uroliths, the urinary bladder was catheterized and the "jiggle technique"1 was used to aspirate some small stones through the urinary catheter into a syringe for quantitative mineral analysis (cvm.umn.edu/depts/minnesotaurolithcenter/home.html). Stones as small as a pinhead can be submitted for analysis. Knowing the mineral composition of uroliths before initiating therapy can help determine whether further diagnostics are warranted and what therapeutic options are available.

Quantitative analysis of uroliths obtained through the catheter revealed that they were composed of 45% MAP and 55% AAU. It is not uncommon for infection-induced struvite uroliths in dogs to have a small amount (< 25%) of AAU with no obvious liver dysfunction. Protein (purine) metabolism in healthy dogs results in excretion of allantoin in urine, as well as small amounts of uric acid. If urine becomes supersaturated with ammonium ions, which is what occurs during formation of infection-induced struvite uroliths, some ions may react with uric acid already present in urine to form AAU. However, if AAU is more than 25% of the mineral composition of uroliths, the possibility of a PSS should be considered. On the other hand, if the mineral composition of the uroliths is 100% AAU, they may not have been visible on survey abdominal radiographs.

To further assess liver function, a serum bile acid test was done on day 2 of admission. The results were elevated (Table 2), and a tentative diagnosis of PSS was made. Based on the breed of this dog, the PSS was probably extrahepatic and amenable to surgical correction.2

Treatment. Treatment initiated on day 1 consisted of oral clavamox for the UTI. The urine culture indicated that the bacteria were susceptible to this antibiotic. A second urine culture done 7 days later was sterile. Antibiotics were continued until the time of surgery.

Cystotomy was performed, and mineral composition of these stones was similar to the stones retrieved via the "jiggle technique." Cranial mesenteric arteriography was done to confirm the diagnosis of PSS and to determine whether it was amenable to surgical correction (Figure 2). The portal postcaval shunt was attenuated 75% at the time of surgery, and postattenuation arteriography was performed (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Cranial mesenteric arteriography done during surgery reveals an unusual PSS, presumably following the left gastric vascular flow and entering the caudal vena cava at the level of the caval hiatus. Some intrahepatic arborization is present. This postcystotomy radiograph also confirms that all the bladder stones were removed from the urinary bladder.

Figure 3. Cranial mesenteric arteriography done after ligation of a PSS reveals no shunting of blood and good intrahepatic arborization.

Outcome. Recovery from surgery was uneventful. The dog was discharged from the hospital 48 hours after surgery, and antibiotics were continued for 14 days.

Ten weeks after surgery, a serum bile acid test was performed and the results were within normal limits (Table 2). The dog lived for 3 more years and eventually died of acute congestive heart failure secondary to mitral insufficiency. Necropsy revealed no recurrence of uroliths.

Discussion. This case illustrates 2 important points: The dog did not present for liver disease, but rather for LUT signs. Had the dog not developed urolithiasis, it is possible that the PSS may never have been detected. There was some intrahepatic arborization of blood before the surgery that may account for why the dog did not show any obvious clinical signs of encephalopathy from the PSS.

Knowing the mineral composition of uroliths before starting therapy facilitates appropriate additional diagnostic tests (in this case, serum bile acid tests) before surgery. In this patient, obtaining a sample of bladder uroliths via the "jiggle technique" provided an important additional clue for pursuing the possibility of a PSS before surgery, even though the age of the patient was atypical for this problem. Had the mineral composition of uroliths not been available until after the cystotomy was performed, it is likely that the patient would have required additional surgery to correct the PSS.

DID YOU ANSWER...

Rectal examination was done not only to rule out uroliths in the urethra, but more important to rule out neoplasia in the urethra. Signs of transitional cell carcinoma are similar to those of UTI or bladder calculi. It is unfortunate to miss this diagnosis because a simple physical examination procedure was not performed.

Crystalluria is an inconsistent finding in dogs with urolithiasis. In a recent study by Lulich, only 19 of 50 (37%) of bichon frise dogs with calcium oxalate urolithiasis had crystalluria.3 Although it is unknown how often crystalluria is present for other mineral types of uroliths in dogs, it is probably similar. If crystals are present, they may not always be indicative of the mineral composition of the uroliths.

Based on results from the urinalysis, urine culture, and abdominal radiographs, the most likely mineral composition of the uroliths is struvite or MAP. Most MAP uroliths in dogs are infection-induced and associated with urease-producing bacteria, such as Staphylococcus intermedius or Proteus species.4 In the urine, urease produced by these bacteria convert urea to ammonia (NH3), and water then combines with ammonia ions to produce ammonium (NH4+) ions and hydroxyl (OH-) ions. Once urine becomes supersaturated with ammonium ions, these ions combine with magnesium and phosphate already present in urine to produce MAP uroliths. Production of hydroxyl ions is why UTIs from urease-producing bacteria cause an alkaline urine pH. The radiographic appearance of uroliths is also consistent with MAP.5

This dog had additional abnormalities that warrant further investigation. The BUN was inappropriately low for an adult dog consuming a complete and balanced maintenance diet. Mild hypoalbuminemia and microcytic, hypochromic red blood cells without anemia were also present, and the liver silhouette on abdominal radiographs appeared smaller than normal. These findings should raise the index of suspicion for a PSS. Further assessment of liver function and mineral composition of the uroliths is warranted before initiating therapy for the uroliths.

Related articles:Treatment of Ectopic UretersEmergency Management of Urethral Obstruction in Male Cats