Leptospirosis in a Dog

J. Scott Weese, DVM, DVSc, DACVIM, FCAHS, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada

An 8-year-old spayed Maltese was presented with anorexia and lethargy of 2 days’ duration.

History

The client reported no other changes in behavior or other remarkable signs. The dog lived in a condominium in an urban area, visited doggy daycare during the day, and was frequently walked in a small park adjacent to the condominium.

Examination, Testing, & Treatment

On presentation, the dog was quiet but alert and responsive. Vital signs were within normal limits; however, mild icterus was noted, and the dog resisted deep abdominal palpation around the kidneys. The dog had been vaccinated (parenteral canine parvovirus, distemper, adenovirus, parainfluenza, rabies) 2 years earlier but not against leptospirosis.

Minor changes consistent with a stress leukogram were present on CBC. Elevations in blood urea nitrogen (77 mg/dL; range, 10.1–25.2 mg/dL) creatinine (2.07 mg/dL; range, 0.2–1.7 mg/dL), ALP (321 U/L; range, 22–143 U/L), ALT (472 U/L; range, 19–107 U/L), and total bilirubin (2.3 mg/dL; range, (0–0.23 mg/dL) and mild decrease in albumin (2.6 g/dL; range, 2.9–4.3 g/dL) were identified on serum chemistry panel. A urine sample revealed a specific gravity of 1.014 with trace protein, 1+ glucose, 2+ bilirubin, pH of 6.8, and 1 WBC/high-power field. Leptospirosis was suspected, and treatment was started with doxycycline,1 along with intravenous fluids and oral famotidine. Urine was submitted for bacterial culture and Leptospira spp PCR analysis. A serum sample was saved for Leptospira spp serology and submitted with a convalescent sample 14 days later.

Ask Yourself

Leptospirosis is a potentially zoonotic disease, but most human infections occur from wildlife sources while few reported cases are from dogs. Nonetheless, enhanced infection control practices should be used to minimize transmission risk.

In this case, enhanced infection controls proved necessary, as the dog was diagnosed with leptospirosis based on a greater than fourfold increase in serum microscopic agglutination test titer against L grippotyphosa (acute 1:100, convalescent 1:1600). Urine PCR testing was negative for Leptospira spp; however, this is not uncommon because of relatively low diagnostic sensitivity. Clinical and laboratory findings, along with positive response to treatment, were consistent with leptospirosis. Fourteen days of treatment with doxycycline was prescribed per standard guidelines.1

Infection Control Practices for Management of Suspected or Confirmed Leptospirosis Cases1,8

House the dog in isolation, when possible.

Start appropriate antimicrobial therapy promptly, before confirmation of leptospirosis, if it is a reasonable differential.

Use enhanced barrier precautions (eg, gloves, gown or dedicated lab coat) when handling the patient or any potentially urine-contaminated items or when working within the patient’s environment.

Wear eye protection and a mask or full-face shield when performing activities that might aerosolize leptospires (eg, handling a urine-soaked animal that might struggle or be excitable).

Wash hands or use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer after glove removal and any contact with the animal or potentially contaminated environments.

Treat soiled laundry, especially urine-soaked bedding, as infectious. Wear gloves and a gown or dedicated lab coat when handling soiled laundry, and wash hands after glove removal.

Restrict contact between leptospirosis patients, suspected cases, and pregnant personnel as possible.

Clean and disinfect any potentially contaminated areas promptly and effectively using a disinfectant effictive against Leptospira spp (eg, accelerated hydrogen peroxide).

Use adequate cage signage so all personnel know the animal is infectious.

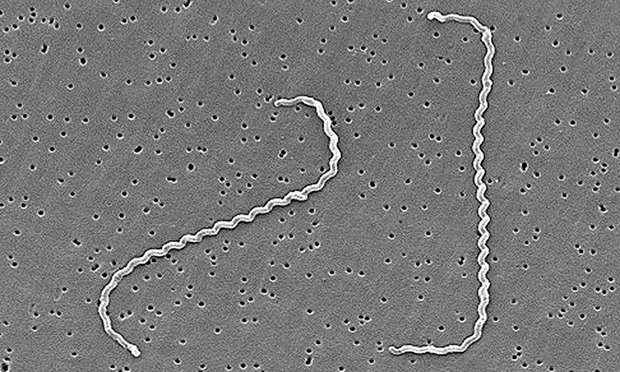

Electron micrograph of Leptospira interrogans. Courtesy Janice Haney Carr

Zoonotic Risk & Recommended Precautions

Leptospirosis, a potentially severe disease caused by Leptospira spp (Figure 1), is considered a reemerging disease in dogs.2 Leptospira spp are widespread in many animal populations. Different serovars have different host ranges and abilities to infect other species. While leptospirosis can vary and be clinically vague, renal and hepatic involvement is common in dogs. Clinicians should be aware of the incidence of leptospirosis in their patient population, and leptospirosis should be considered in patients that are from (or have travelled to) endemic regions.

Antimicrobial and supportive therapy can be highly effective if instituted early. Hospitalization is often required for initial management, particularly for IV therapy. This can create potential infection control concerns because affected animals may shed infectious leptospires in urine, potentially exposing other animals and human caretakers.

Leptospirosis is a potentially serious zoonotic disease; most human infections occur from indirect animal contact (exposure to wet soil or water contaminated with urine from reservoir wildlife species). Direct transmission from infected pets is uncommon but has been reported, usually from pet rats.3-5 Zoonotic infection of veterinary personnel from infected dogs has been reported,6,7 and the author is aware of multiple additional cases (usually veterinary technicians) associated with handling infected dogs or urine-contaminated items in veterinary clinics. Therefore, while the incidence of disease is likely low, the degree of risk and potential disease severity indicate a need for prudence.

As with most aspects of infectious disease control in the veterinary setting, little objective information defining optimal practices for management of patients with leptospirosis is available. However, basic principles of infection control combined with an understanding of the biology of Leptospira spp and the disease pathophysiology permit development of logical empirical recommendations (see Infection Control Practices for Management of Suspected or Confirmed Leptospirosis Cases<sup1,8)sup>. These measures should lower the risk for human infection while allowing proper patient care and effective clinic operations.

Furthermore, the period in which there is realistic risk for infection is short. Although clear data are limited, it is expected that Leptospira spp shedding will stop within 48 to 72 hours after appropriate antimicrobial therapy1,8 has started if not sooner. Therefore, focusing on aggressive infection control in the first few days of hospitalization is key. Some facilities discontinue enhanced precautionary measures after 2 to 3 days of antimicrobial treatment—a reasonable approach, although data to support it are lacking. Additionally, before declaring them low risk, some facilities bathe affected dogs with a biocide that would be antileptospiral (eg, chlorhexidine, accelerated hydrogen peroxide) on the assumption that viable leptospires might be living in warm, moist areas of the haircoat that were contaminated with urine. Whether this is truly necessary is unclear, but this easy and practical measure may provide an added level of protection.

Questions about potential risks for leptospirosis exposure in humans often arise, particularly when precautions were inadequate in initial treatment. Post-exposure treatment for humans exposed to infected animals is rare,8 but there are no clear guidelines. Having potentially exposed individuals monitor themselves for early signs of infection (eg, fever, flu-like symptoms) is common, and all individuals should consult a physician on a case-by-case basis to determine the need for postexposure prophylactic treatment (commonly prescribed to pregnant women because of the potential for spontaneous abortion).8,9 Potentially exposed personnel should consult with a physician to determine whether postexposure treatment is necessary.

The Take-Home

Zoonotic leptospirosis from infected dogs is rare but does occur.

Consultation with a physician should be scheduled for individuals who may have been exposed, but prophylactic treatment is uncommon.

Good routine infection control practices and use of enhanced precautions for animals with a reasonable likelihood of having leptospirosis are important to reduce exposure risk