Canine Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia

Michael J. Day, BSc, BVMS (Hons), PhD, DSc, DiplECVP, FASM, FRCPath, FRCVS, University of Bristol

Profile

Definition

Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA) occurs when antibodies and complement molecules of the immune system target RBCs for destruction via macrophage phagocytosis in the spleen or liver (extravascular hemolysis) or complement-mediated cytolysis within the circulation (intravascular hemolysis).1

IMHA can be an idiopathic autoimmune event (primary IMHA) or associated with trigger factors (secondary IMHA).

It can be the sole immune event or occur with other immune-mediated processes (eg, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia [IMTP]).2

Systems

The condition reflects abnormal function of the immune system expressed by targeted destruction of one part of the hematopoietic system (erythroid lineage).

Subsequently, the effects of hemolytic anemia involve many body systems.

Genetic Implications

Primary idiopathic canine IMHA has a clear genetic basis as shown by distinct breed and familial clustering.

Studies of genomic variation in affected versus normal dogs of predisposed breeds are currently being conducted.3

Incidence/Prevalence

IMHA is the most common immune-mediated disease of dogs.

There are no true prevalence data, but most generalists should expect to see this disease at least once a year.

Geographic Distribution

Canine IMHA occurs globally.

In parts of the world where arthropod-borne infections are endemic, the disease is more often secondary.4

Signalment

Breed Predilection

Predisposed breeds include the cocker spaniel, springer spaniel, and Old English sheepdog.3

In North America, the clumber spaniel is at risk.

In some countries, inbreeding has created particular susceptibilities (eg, the Maltese in southeastern Australia).5

Age & Range

IMHA is primarily a disease of middle-aged to older dogs.

It may occur at any age but is rare in dogs younger than 1 year.

Sex

There is no clear sex predisposition for canine IMHA, although the stress of estrus and whelping are suggested triggers.

Causes & Risk Factors

The cause of primary idiopathic (autoimmune) IMHA remains enigmatic.

Some dogs may develop an imbalance in immunity in which there is decreased function of immune cells designed to control autoreactive responses (T regulatory cells).

This permits abnormal activation of immune cells that initiate the autoimmune response (T helper cells) and subsequently drive autoreactive B cells to produce the causative autoantibodies specific for RBCs.1

Secondary IMHA likely involves similar immunologic events triggered by particular events or secondary to other underlying diseases.

The most common infectious causes involve the arthropod-borne agents Babesia, Ehrlichia, and Leishmania spp.4

IMHA is sometimes documented in association with lymphoma, hemangiosarcoma, or bone marrow myeloproliferative disease.

There is increasing recognition that IMHA may occur in association with idiopathic inflammatory disease (eg, inflammatory enteropathy).

IMHA may be triggered by exposure to a range of drugs.

Although controversial, it has been noted that, in the absence of other recognized trigger factors, IMHA may arise within 2–4 weeks of recent vaccination.7

Pathophysiology

In most cases, the immune system targets circulating RBCs.

Extravascular hemolysis, generally mediated by IgG antibodies, is a chronic process that allows physiologic compensation for the anemic state and regenerative bone marrow response (Figure 1A).

In contrast, intravascular hemolysis, generally mediated by IgM antibodies, is an acute process involving sudden massive destruction of circulating RBCs.8,9

This causes acute collapse with hemoglobinemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and hemoglobinuria (Figure 1B).

In some cases, the immune response may target bone marrow erythroid precursors, leading to nonregenerative IMHA or pure red cell aplasia (PRCA).

Concurrent IMHA and IMTP (Evans syndrome) involves production of additional antiplatelet antibodies.

Immune-mediated neutropenia (IMNP) is now recognized as a third part of this disease spectrum.2

Dogs often have hypercoagulability.10

Figure 1 Pathogenesis of IMHA. (A) Extravascular hemolysis occurs when macrophages in the spleen or liver phagocytose and remove antibody- and/or complement-coated RBCs. (B) Intravascular hemolysis occurs when antibody- and complement-mediated lysis of RBCs occur within the circulation, leading to release of free hemoglobin (Hb) into the plasma.

Signs

The most common clinical presentation (Figure 2) is a 1–2 week history of increasing weakness, lethargy, and exercise intolerance with signs related to chronic hemolytic anemia (eg, mucous membrane pallor, tachycardia, tachypnea, hepatosplenomegaly).

Signs primarily reflect extravascular hemolysis.

Close attention should be paid to respiratory function, as secondary pulmonary thromboembolism is increasingly recognized as a complication.

A less common presentation is acute history of collapse, jaundice, and hemoglobinuria reflecting intravascular hemolysis.

In some dogs, elements of both pathophysiologic mechanisms may be identified.

Figure 2 Pale oral mucous membranes in a 6-year-old cocker spaniel with IMHA. This dog had a 10-day history of increasing weakness and lethargy, PCV of 18%, and positive Coombs test result.

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis is provided by demonstration of antibody and/or complement attached to the surface of RBCs.

Diagnosis involves identification of hematologic and immunologic abnormalities and rigorous search for underlying disease or historical trigger factors.

Thorough history and investigation for potential neoplastic or idiopathic inflammatory disease are vital.

Laboratory Findings

First line of diagnosis is hematologic.

In-saline agglutination (ie, autoagglutination) test is a useful starting point.

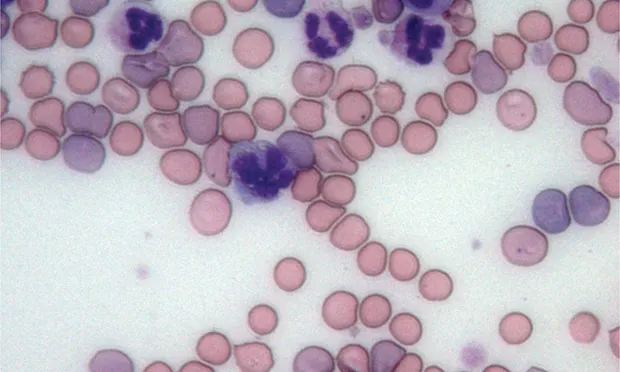

Routine hematologic examination must include evaluation/assessment of blood smear (Figure 3) for:

RBC morphologic changes (eg, polychromasia, spherocytosis, nucleated erythrocytes).

Microparasites.

Platelets and leukocytes.

Figure 3 Blood smear from a dog with Coombs-positive IMHA. There are numerous large polychromatic cells (P), which are likely reticulocytes. Regeneration is also suggested by the presence of a nucleated erythrocyte (blunt arrow, NE). Spherocytes (S) are also prominent and strongly indicate immune-mediated hemolysis. In this instance, IMHA was secondary to Babesia gibsoni infection, as shown here (long arrow). Bar = 10 μm.

An evaluation of regenerative response is essential.

Serum biochemistry profile can characterize features of hemolytic anemia and may assist in identifying underlying disease processes.

Increased liver enzyme activities are common and thought to relate to anoxia and death of centrilobular hepatocytes in chronic anemia.

If clinical history or presentation suggests arthropod-borne infection, appropriate serologic or PCR testing should be performed.

Traditional methods of demonstrating RBC-associated immune reactants are via Coombs test or direct antiglobulin test.11-15

Many variants of the Coombs test are available.

Typically, the more complex the Coombs test (ie, multiple reagents, full titration of reagents, performance of the test at both 4°C and 37°C), the greater the likelihood of obtaining a positive result (Figure 4).

Because not all laboratories offer such a complex Coombs test, IMHA is not ruled out in a Coombs-negative patient with compatible clinical signs and hematologic changes (eg, autoagglutination, spherocytosis).

Some laboratories now offer flow cytometric testing for detecting RBC-bound immune reactants, but there is reportedly wide variation in the sensitivity and specificity of this method compared with the Coombs test.

Figure 4 Canine Coombs test: A positive reaction occurs when (row A, first wells) antiglobulin causes RBCs to form an agglutinate over the base of the well. When (row E) cells form a small button at the base of the well, the reaction is negative. In this test, (row A) there are positive reactions with polyvalent canine Coombs reagent, (row B) anti–dog IgG, and (row C) anti–dog IgM, but (row D) no significant reaction with anti–dog complement C3.

Postmortem Findings

Postmortem findings depend on whether underlying disease was present and the pathophysiology of disease.

Treatment

Medical

Glucocorticoid Therapy

Most dogs with chronic, physiologically compensated, regenerative hemolytic anemia require only immunosuppression with oral prednisolone at the standard immunosuppressive dose (1 mg/kg q12h) given to clinical effect with slow tapering and eventual withdrawal.16

Some patients relapse repeatedly when treatment q48h is withdrawn and require long-term low-dose maintenance therapy.

Gastroprotectants should be administered to dogs receiving immunosuppressive glucocorticoid therapy.

Adjunct Immunomodulatory Drugs

If disease severity is sufficient to justify inclusion of an adjunct immunomodulatory drug with glucocorticoid therapy, it is important to start it from the outset, as some agents have a lead-in time before they take effect.17,18

The most widely used agent is azathioprine (2 mg/kg q24h).

Cyclophosphamide should not be used in this context.19

Although referral veterinarians may use other immunomodulatory drugs, such as cyclosporine (5 mg/kg q12–24h), leflunomide (2 mg/kg q12h), or mycophenolate mofetil (12–17 mg/kg q24h or divided doses q12h), few peer-reviewed studies have investigated these agents for use in dogs with IMHA.16

Other Therapeutics

Prophylactic Anticoagulants

Thromboembolic complications have triggered use of prophylactic anticoagulants, such as aspirin or heparin, in low or ultra-low dose regimens.20

Blood Transfusion

Although transfused RBCs may become a target for immune attack in a dog with IMHA, there is no rationale for withholding transfusion in a dog with markedly decreased PCV.

The ideal transfusion for most dogs with IMHA is packed RBCs.

IV Human Immunoglobulin

For refractory cases, administration of high doses of human Ig blocks Fc receptors on macrophages and inhibits extravascular hemolysis.

This product may be used in management of cases, but the danger of sensitization with multiple administrations must be considered.16,18

General Treatment Considerations

Treatment of underlying disorders is integral to the management plan.

IMHA is an immune-mediated disease reflecting inappropriate and overexuberant activity of the immune system.

The logical approach may involve suppression of the inappropriate immune response, but this presents 2 problems:

There is no textbook IMHA; each patient must be considered individually and therapy tailored to the clinical, hematologic, and immunologic severity of the disease.

There is no single correct way to implement medical immunosuppression.

The challenge lies in coordinating a large, multicenter, controlled treatment trial.

Current literature describes the experience of individual referral institutions and often compares outcomes for patients receiving monotherapy or combination therapies.16,19

In a clinical setting, patients with more severe disease are generally candidates for combination therapy and therefore have a poorer prognosis at the outset.

In that context, the decision to implement immunosuppressive glucocorticoid therapy alone or in combination with an adjunct immunomodulatory drug is based on clinical acumen and assessment of whether disease severity and degree of anemia and regeneration justify a more aggressive therapeutic approach.

Follow-Up

At the referral level, approximately 50% of dogs die within 14 days of admission.21,22

However, dogs with IMHA can be treated successfully and immunomodulatory therapy can be withdrawn after tapering.

Owners must be warned that a dog with genetic susceptibility to immune-mediated disease may typically have recurrent disease months or years into the future and that sometimes other immune-mediated diseases may arise subsequently.

In General

Relative Cost

Thorough diagnostic approach may include a combination of modalities: $$–$$$$$

Treatment costs depend on drugs, supportive measures, and disease severity: $$–$$$$$