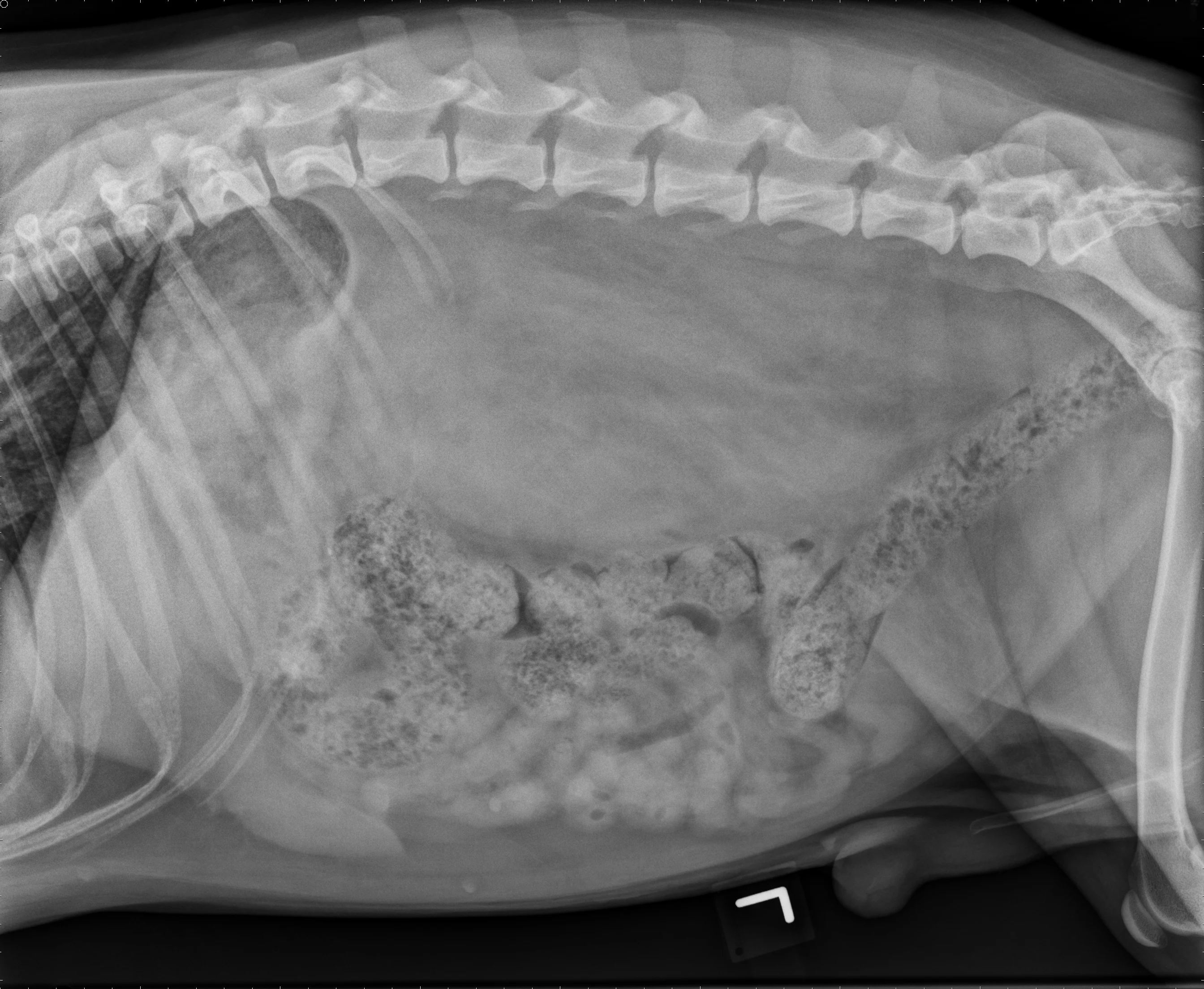

Retroperitoneal effusion in a dog

Updated August 2025 by Ashley L. Ayoob-Wagner, DVM, DACVECC, DACVIM; BluePearl Pet Hospital, Northfield, Illinois

You asked…

What is hypovolemic shock, and how should it be managed?

The expert says…

Shock, a syndrome in which clinical deterioration can occur quickly, requires careful analysis and rapid treatment. Broad definitions for shock include inadequate cellular energy production or the inability of the body to supply cells and tissues with oxygen and nutrients and remove waste products. Shock may result from a variety of underlying conditions and can be classified into the broad categories of distributive, hemorrhagic, obstructive, and hypovolemic.1-5 Regardless of the underlying cause, all forms share a common concern: inadequate perfusion.3,4 Perfusion (ie, blood flow to or through a given structure or tissue bed) is imperative for nutrient and oxygen delivery, as well as removal of cellular waste and byproducts of metabolism. Lack of adequate perfusion can result in cell death, morbidity, and mortality.

Hypovolemic shock is one of the most common categories of shock seen in veterinary medicine.6 With hypovolemic shock, perfusion is impaired as a result of an ineffective circulating blood volume caused by loss of intravascular volume that occurs secondary to a loss in total extracellular fluid or secondary to blood loss.1 During initial circulating volume loss (10% total blood volume loss), a number of compensatory mechanisms occur in response to decreased perfusion, leading to an increase in sympathetic tone and a secondary increase in heart rate, cardiac contractility, and peripheral vasoconstriction,1,2 as well as increased levels of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate,resulting in a rightward shift in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve and decreased blood viscosity. When ≈30% of blood volume is lost, however, a lack of oxygen delivery leads to a loss of adenosine triphosphate production, causing a shift from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism with ensuing lactic acidosis and possible failure of compensatory mechanisms,1,2 resulting in organ dysfunction. Causes of hypovolemia include hemorrhage (eg, surgery, trauma, neoplasia, anticoagulant rodenticide ingestion); fluid loss from vomiting, diarrhea, or renal disease; severe burns; and third-space losses (eg, edema, ascites).3,4

To Compensate, or Not to Compensate…

In states of hypovolemia, the body has a compensatory neuroendocrine response to improve circulating blood volume and metabolic demands.

The body senses these changes in several ways including the following.3,4

When blood flow to the tissues is decreased, oxygen extraction from the blood delivered to the microcirculation is increased.

Stretch receptors and baroreceptors in the left atrium, aortic arch, carotid body, and splanchnic vessels detect a decrease in stretch of the endothelium secondary to a decreased filling of vessels, leading to activation of these receptors.

Hypoxemia is detected by chemoreceptors in the carotid artery and aorta.

Development of metabolic acidosis stimulates peripheral and central chemoreceptors.

Decreased oxygen delivery to local tissues triggers production of local metabolites, an increase in the number of open capillary beds, and activation of intrinsic myogenic autoregulation of vessel tone.

The body responds to these changes in several ways.

Hormonal mediators, including epinephrine, norepinephrine, angiotensin, renin, and aldosterone, are released in the intermediate phase of hypoperfusion, resulting in water and sodium retention, increased heart rate, increased cardiac contractility, selective vasoconstriction, and redistribution of flow to vital organs.

Peripheral vagal stimulation and increased sympathetic stimulation result in vasoconstriction of the precapillary arteriolar sphincters, increased heart rate, and increased cardiac contractility.

Movement of fluid from the interstitial and intracellular spaces into the intravascular space is caused by an altered transcapillary pressure gradient (increased intravascular colloid oncotic pressure, decreased intravascular hydrostatic pressure).

Vasopressin is released, binding to V1 receptors within the vasculature leading to vasoconstriction and binding to V2 receptors in the collecting ducts of the kidney leading to reabsorption of water.

Increased fluid retention by the kidneys results from an upregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and the influence of antidiuretic hormone and atrial natriuretic peptide.

In cases in which perfusion becomes compromised in spite of these mechanisms, cellular death and decompensatory hypovolemic shock ensues.

Clinical Clues

Clinical signs of hypovolemic shock in dogs include tachycardia, decompensated shock (ie, compensatory mechanisms cannot respond to ongoing blood loss), altered mentation, pale mucous membranes (Figure 1), prolonged capillary refill time, weak femoral pulses, cold extremities, tachypnea, and hyperlactatemia. Cats often bypass the compensatory responses commonly seen in dogs and are presented with hypotension, bradycardia, and hypothermia.7-9 Assessment of lactate clearance over time and shock index (heart rate/systolic blood pressure) have shown promise in the detection of ongoing subclinical hypoperfusion, with higher numbers indicating more severe shock. A suggested shock index cutoff level of >0.9 indicates the need for ongoing resuscitation. Clinical signs of hypovolemic shock may help with differentiation from other causes of shock, like cardiogenic shock (may include loud heart murmur, tachycardia or bradycardia, arrhythmias, weak heart sounds) or distributive shock (eg, bright red mucous membranes [Figure 2], bounding femoral pulses).3,4

Pale pink mucous membranes in a dog with hypovolemic shock

Injected (ie, bright red) mucous membranes in a dog with distributive shock

Treatment

Rapid fluid administration is the mainstay of therapy. Isotonic crystalloid fluids (eg, lactated Ringer’s solution, 0.9% saline) are often used initially (Table 1).10,11 Shock doses of fluids are 90 mL/kg for dogs and 44 to 60 mL/kg for cats.12 The entire shock dose is not administered initially. An initial bolus of 20 to 25 mL/kg for dogs and 10 to 20 mL/kg for cats should be administered over 15 to 30 minutes, followed by patient reassessment (eg, heart rate, capillary refill time, mucous membrane color, core body temperature, blood pressure, lactate levels, shock index). These boluses can then be repeated until clinical resolution of hypoperfusion is obtained or the full shock dose has been administered. In dogs, a simple method to calculate one-quarter shock volume is to take the patient’s weight in pounds and add a zero, indicating the amount of fluid in milliliters to administer as a bolus over 15 to 30 minutes.

Crystalloids alone may be insufficient to restore intravascular and interstitial volume if underlying or compounding diseases are present, including head trauma, pulmonary trauma, and/or hypoproteinemia; compounding diseases and hypoproteinemia can lead to edema formation. Synthetic colloid fluids may be advantageous if used with caution in patients with, or at risk for, edema formation (Table 2). Use of synthetic colloids is controversial, as impaired renal function and coagulopathy have been reported, the volume of fluid for resuscitation is not significantly lower than with crystalloids alone, and studies reveal no difference in mortality of critical patients with synthetic colloids versus crystalloids alone.13 Hydroxylethyl starch in sodium chloride solutions are the most common synthetic colloid choices, with bolus dose recommendations of 2 to 5 mL/kg for cats and 3 to 5 mL/kg for dogs. These doses can be repeated until clinical resolution of hypoperfusion is obtained or a suggested therapeutic dose of 20 mL/kg total has been administered.14

For cases with head trauma or pulmonary injury, hypertonic saline may be considered, as it draws fluid from the interstitial spaces to the intravascular space, resulting in a rapid but transient increase in effective circulating volume; 7.5% hypertonic saline is commonly used at 4 to 8 mL/kg via bolus.15 Hypertonic solutions should be avoided in dehydrated or hypernatremic patients because of possible undesirable effects (eg, cellular dehydration, stimulating diuresis before adequate plasma volume expansion has been achieved).

In cases in which hemorrhage is the underlying cause of hypovolemic shock, additional considerations include definitive control of bleeding and blood product administration. When treating anemia, administration of ≈10 mL/kg packed RBCs or 30 mL/kg fresh whole blood raises the hematocrit by ≈10%.14,16 In cases of trauma with severe hemorrhage, special considerations for the coagulopathy of trauma and massive transfusion should be considered. The definition of massive transfusion has been extrapolated from human medicine as blood loss exceeding that of the circulation blood volume in 24 hours or a 50% loss of circulating volume within 3 hours.17,18 Massive transfusion protocol recommendations include the use of fresh whole blood or administration of blood products at a ratio of 1:1:1 or 1:1:2 (fresh frozen plasma:frozen or lyophilized platelet concentration:pRBCs). Concurrent use of antifibrinolytics, aminocaproic acid, or tranexamic acid can also be considered.2,19

When Is Enough, Enough?

For hypovolemic shock, fluids are administered to reach certain endpoints of resuscitation. The endpoint typically reflects an improved or restored perfusion status of the patient, including normalization of the heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature, mucous membrane color, capillary refill time, and pulse quality.

Several studies have highlighted that evaluation of traditional perfusion parameters alone may underdiagnose a state of persistent tissue hypoxia in up to 94% of critically ill patients. Lactate evaluation and shock index are both rapid point-of-care diagnostics that have clinical utility in the detection of occult hypoperfusion.20 Evaluation of lactime and lactate clearance have shown clinical utility in the identification of ongoing hypoperfusion and prediction outcome in dogs with shock, with survivors having significantly lower values than nonsurvivors in both parameters.7,8 Shock index has been documented to be significantly higher in patients with ongoing tissue hypoxia and may identify occult hypoperfusion in both dogs and cats, with a suggested cutoff of >0.9 to be consistent with shock and values >1.4 to be consistent with severe shock; however, defined clinical cutoff points still need to be established.

Key Clinical Parameters Used to Assess Shock

Lactime: duration of time lactate >2.5 mmol/L

Lactate clearance: (lactate initial – lactate delayed)/(lactate initial × 100)

Shock index: heart rate/systolic blood pressure

If signs of hypovolemic shock persist despite the perception of adequate fluid administration, reasons for endpoint failure should be considered, including inadequate volume administration, ongoing hemorrhage, third-spacing of fluid (ie, movement of fluid into the interstitial space or body cavities), heart disease, inappropriate vasomotor tone, or metabolic illness (eg, metabolic acidosis, hypoglycemia).

If an appropriate shock fluid volume has been administered and appears adequate and the patient is still hypotensive, vasopressors may be considered (Table 3).21