Fever, Lameness, & Heart Murmur in a Coonhound

A 10-year-old, 24-kg spayed female treeing walker coonhound was presented for a 3-month history of anorexia, lethargy, weight loss, and a newly auscultated heart murmur.

HistoryAccording to the owners, the dog lost interest in eating 3 months earlier and became lethargic several weeks prior to presentation. No vomiting, diarrhea, or change in thirst or urination was reported.

In addition, the owners described an intermittent weight-bearing lameness/stiffness in the hindlimbs. The lameness began in the right hindlimb approximately 1 month earlier, then shifted to the left hindlimb.

Related Article: The Risks & Challenges of Bartonella

The patient was a hunting dog, lived outdoors with 30 other dogs, and was mostly unsupervised. Due to progressive lethargy and lameness, the dog had not been hunting in several weeks. The dog had no previous health problems or trauma, was vaccinated 10 months earlier, and received monthly heartworm preventive (ivermectin) but no flea or tick preventive.

Physical ExaminationThe dog was quiet but panting. Body condition score was 3/9. Its mucous membranes were pink, rectal temperature was 102.9° F, and heart rate was 100 beats/min with normal sinus rhythm. A grade III/VI left basilar diastolic murmur was auscultated. Femoral arterial pulses were bounding, synchronous, and symmetrical. The dog was ambulatory and had a normal gait. No joint swelling or pain was noted, and no neurologic abnormalities were detected.

Laboratory ResultsHematologic abnormalities included leukocytosis characterized by mature neutrophilia (15 ¥ 103/mcL; reference interval, 2.84–9.11) and mild monocytosis (1.064 ¥ 103/mcL; reference interval, 0.075–0.85). The patient was hypoalbuminemic (albumin 2.3 g/dL; reference interval, 2.5–4.4) and globulins were 4.4 g/dL (reference interval, 2.3–5.2). Urinalysis findings included a urine specific gravity of 1.025, with no proteinuria, glycosuria, pyuria, or cylindruria.

Related Article: Dog-to-Veterinarian Transmission of Bartonella

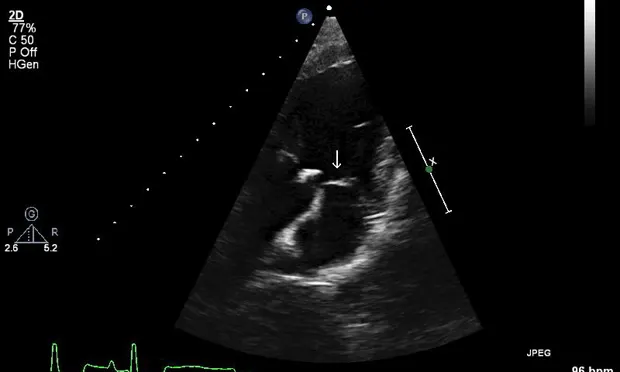

Imaging ResultsThoracic radiographs and abdominal ultrasound were unremarkable. Two-dimensional, M-mode, color flow, and spectral Doppler echocardiography demonstrated a vegetative lesion associated with the aortic valve, moderate aortic regurgitation, mild thickening of the mitral valve, and mild left atrial enlargement (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 (above): Left parasternal long-axis view: A hyperechoic lesion associated with the aortic valve was noted (arrow), consistent with a vegetative endocarditis lesion.

Figure 2 (below): Left parasternal long-axis view: Color flow echocardiography showed moderate aortic valve regurgitation.

ASK YOURSELF...• What further diagnostics are indicated at this point?• What are the most common bacterial causes of endocarditis in dogs?

DIAGNOSIS:Aortic valve endocarditis due to Bartonella vinsonii berkhoffii

Diagnosing Bartonella endocarditis can be very challenging. It is recommended to obtain serology, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and Bartonella_alpha _Proteobacteria growth medium (BAPGM) culture, specifically for Bartonella species, in order to enhance diagnostic sensitivity.

Related Article: Gammopathy? Think Bartonellosis

Additional DiagnosticsThree 10-mL blood samples were collected aseptically Q 1 H from different sites, submitted for aerobic and anaerobic blood culture, and tested negative. The results of the Snap 4Dx test (idexx.com) for detection of Anaplasma species, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Ehrlichia canis antibodies and for Dirofilaria immitis antigen were negative.

BAPGM culture and PCR successfully amplified Bartonella vinsonii berkhoffii DNA from the blood. In addition, the dog was B vinsonii berkhoffii seroreactive by indirect immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) testing at a titer of 1:120.

Radiographs of the hindlimbs revealed mild joint effusion in the left stifle. Arthrocentesis was declined.

BAPGM = Bartonella alpha Proteobacteria Growth Medium; IFA = immunofluorescent antibody; PCR = polymerase chain reaction

TreatmentTreatment for Bartonella endocarditis includes:

Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy while cultures are pending using a combination of fluoroquinolone and a penicillin-based antibiotic, and/or aminoglycosides, with careful monitoring of renal values

Combination of azithromycin/rifampin or azithromycin/enrofloxacin to treat life-threatening conditions, such as endocarditis or meningitis associated with _Bartonella_species.

Unfortunately data from controlled efficacy studies with long-term follow-up are lacking, and in some cases therapeutic elimination of Bartonella infection remains a challenge.

In this case, antibiotic therapy included ampicillin/sulbactam (22 mg/kg IV Q 8 H), enrofloxacin (10 mg/kg IV Q 24 H), and azithromycin (10 mg/kg PO Q 24 H). The dog was discharged 2 days after admission, and prescribed azithromycin, enrofloxacin, and amoxicillin/clavulanate.

Bartonella Endocarditis

EndocarditisEndocarditis is a relatively uncommon but life-threatening condition. Death can result from congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, pulmonary or systemic emboli, or septicemia. Diagnosis of endocarditis can be challenging, requiring clinical, microbiologic, and echocardiographic criteria to arrive at a definitive diagnosis.

Large-breed dogs are most commonly affected, and clinical signs can be highly variable. Lameness is the most commonly reported presenting complaint, and fever is often present (50%–74%). However, a new heart murmur is auscultated in just 40% of cases. Generally, causative bacteria are identified in 50% to 60% of cases.

Did You Answer...

Further diagnostic tests should include aerobic and anaerobic blood cultures, Bartonella serology, and BAPGM culture/PCR. An abdominal ultrasound would be indicated to look for a source of infection that could have resulted in bacteremia. Joint taps (more than 1 joint) with bacterial cultures are also recommended to further investigate the cause of the dog’s lameness.

Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Escherichia coli species are the most common bacterial isolates in dogs. Since B vinsonii berkhoffii was originally isolated from a dog with endocarditis in 1993, Bartonella species are now considered an important cause of blood culture–negative endocarditis in dogs and humans and may account for up to 20% of cases.

Follow-Up & OutcomeAccording to the owners, the dog’s appetite and energy level dramatically improved. She did not show any lameness thereafter. One week after diagnosis, the dog was alert, responsive, had gained 2 kg, and was normothermic (99.8° F).

Repeat echocardiogram 2 weeks later showed a persistent oscillating aortic vegetative lesion that had decreased in size, severe aortic insufficiency with progressive left ventricular enlargement, left atrial enlargement, and persistent mild mitral valve regurgitation. Enalapril and atenolol were prescribed. Antibiotic treatment was continued for 3 months.

Three months later BAPGM culture and PCR failed to detect Bartonella species DNA in the blood. Follow-up echocardiogram before discontinuation of antibiotic therapy was declined, but subsequent phone communications with the owner revealed that the patient was reportedly healthy 3 months after finishing antibiotic therapy. Follow-up Bartonella IFA was recommended, but declined by the owner.

Treatment with enalapril and atenolol were continued as previously prescribed for persistent aortic insufficiency and mitral valve regurgitation.

BartonellosisBartonella species have been recognized as an important cause of culture-negative endocarditis in dogs since B vinsonii berkhoffii was first isolated from a dog in 1993. Unfortunately, the exact mode of transmission of canine bartonellosis remains unknown. Although B vinsonii berkhoffii is presumably transmitted to dogs by the bite of an infected tick, this mode of transmission has not been proven.

There appears to be a strong predisposition for these organisms to infect the aortic valve, which is affected in 70% of cases. The duration of illness is highly variable with both acute and chronic presentations. The chief complaints are also variable, with clinical signs ranging from fever, lameness, and weight loss to acute fulminant heart failure.

PrognosisPrognosis for aortic endocarditis is typically considered grave, with 33% mortality in the first week and 92% mortality within 5 months from diagnosis. Mortality is often a result of congestive heart failure or sudden death. However, multiple incidents of successful treatment of Bartonella endocarditis have been reported, which suggests that early diagnosis and treatment may result in a better prognosis.

FEVER, LAMENESS, & HEART MURMUR IN A COONHOUND • Cristina Perez & Adam Birkenheuer

Suggested Reading

Bartonella spp. in pets and effect on human health. Chomel BB, Boulouis HJ, Maruyama S, Breitschwerdt EB. Emerg Infect Dis 12:389-394, 2006.Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and related members of the alpha subdivision of the Proteobacteria in dogs with cardiac arrhythmias, endocarditis, or myocarditis. Breitschwerdt EB, Atkins CE, Brown TT, et al. J Clin Microbiol 37:3618-3626, 1999.Bartonellosis. Guptill L. Vet Microbiol 140:347-359, 2010.Canine bacterial endocarditis: A review. Peddlel G, Sleeper M. JAAHA 43:258-263, 2007.Clinicopathologic findings and outcome in dogs with infective endocarditis: 71 cases (1992-2005). Sykes JE, Kittleson MD, Chomel BB, et al. JAVMA 228:1735-1747, 2006.Endocarditis in a dog due to infection with a novel Bartonella subspecies. Breitschwerdt EB, Kordick DL, Malarkey DE, et al. J Clin Microbiol 33:154-160, 1995.Evaluation of the relationship between causative organisms and clinical characteristics of infective endocarditis in dogs: 71 cases (1992-2005). Sykes JE, Kittleson MD, Pesavento PA, et al. JAVMA 228:1723-1734, 2006.Infective endocarditis in dogs: Diagnosis and therapy. Macdonald K. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 40:665-684, 2010.