Feline Injection-Site Sarcoma

You have asked…What is the ideal way to identify and approach feline injection-site sarcoma?

Feline injection-site sarcomas (ISSs) primarily arise at sites of vaccination (called vaccine-associated sarcomas) but have also been associated with administration of injectable lufenuron, microchips, and long-acting antibiotics or corticosteroids. ISSs have been described at locations where nonabsorbable suture materials have been used. Varying lengths of latency (4 weeks to 10 years) between the inciting event and diagnosis of sarcoma have been reported.1

Update: Feline Injection-Site Sarcoma

DiagnosisExamination of an incisional biopsy specimen is recommended for suspected ISS. The specimen should be obtained from an easily excised site without further extension of the surgical field. Excisional biopsy specimens are contraindicated because of increased risk for tumor recurrence and decreased disease-free intervals and survival times.1,2

Fine-needle aspiration and cytology and small trucut biopsy specimens are not recommended for suspected ISS, as the extensive inflammation found in these tumors can lead to a misdiagnosis of granuloma. Most ISSs are fibrosarcomas, but osteosarcomas, chondrosarcomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, and undifferentiated sarcomas have also been reported.

After ISS diagnosis is suspected or confirmed, staging should include a minimum database (CBC, serum biochemical panel, urinalysis) and 3-view thoracic radiography. Abdominal ultrasonography should also be considered for caudally located tumors.1

Histopathologic Identification

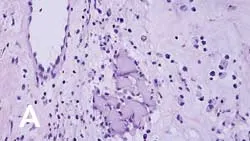

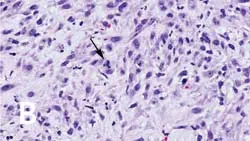

On histopathologic examination, transition zones are present from inflammation to sarcoma, and sarcoma foci are found in areas of granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1). It is hypothesized that postinjection inflammatory reactions, with the release of cytokines and growth factors, result in uncontrolled fibroblast and myofibroblast proliferation, leading to malignant transformation.

_Figure 1 (View larger image). Injection-site sarcoma associated with rabies vaccine administered 7 months prior to diagnosis. (A) Region showing granuloma formation and (B) sarcoma region with cells exhibiting criteria of malignancy, including bizarre mitotic figures (arrow).

_

Treatment

Surgical InterventionSurgery is an important component of treatment for ISS. Because these tumors are poorly encapsulated and extend along and infiltrate fascial planes, referral and advanced imaging are recommended prior to surgery.

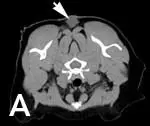

Tumor volume on CT scans with contrast has been shown to be approximately double that of tumor volume measured with calipers on examination4 (Figure 2). This underscores the aggressive nature of ISS as well as the importance of advanced imaging for treatment planning.

An aggressive first resection offers the best chance for local control. Current treatment recommendations include surgical margins of 3 to 5 cm.1,4 Excisional biopsy or marginal resection are not used for ISSs; median time to tumor recurrence with marginal excision is only 79 days, compared with 325 to 419 days following wide excision or radical surgery.2

Based on tumor location, propensity for tumor invasion into surrounding tissue, and the need for wide margins, it is recommended that the initial surgery be performed at a referral institution following CT scan or MRI for surgical planning. The median time to first recurrence is 66 days when the first surgery is performed at a nonreferral institution and 274 days at a referral institution.3 However, despite extensive planning and wide or radical margins, local control is still poor with surgery alone. Complete surgical margins are achieved in only 50% of cats with aggressive surgery, and the 1- and 2-year disease-free intervals are 35% and 9%, respectively.1

Figure 2 (View larger image). CT scan of a cat with recurrent intrascapular injection site-sarcoma. (A) Intrascapular mass (arrow) palpable on examination and (B) extension of mass caudally and laterally (arrows).

Radiation TherapyWith the high recurrence rates of surgery alone, radiation therapy is commonly used pre- or postoperatively to increase the disease-free interval of cats with ISS. When used preoperatively, local tumor recurrence following radiation and surgery is 40% to 45% at a median of 39 to 584 days. However, if complete margins are achieved with surgical excision, the median disease-free interval is reported as 700 to 986 days postoperatively as compared with 112 to 292 days with incomplete margins.5,6 The use of postoperative radiation therapy offers similar results, with a median progression-free interval of 37 months.7 However, recurrence rates are still approximately 40% within 1 to 2 years of treatment, even with the use of pre- or postoperative radiation therapy.5-7

ChemotherapyThe role of chemotherapy has not yet been defined. The overall response rate in patients with gross disease is 33% with the use of doxorubicin alone and 41% with ifosfamide alone. However, the median time to progression following either chemotherapeutic protocol is short, ranging from 70 to 84 days.8,9 Chemotherapy may be beneficial postoperatively when radiation therapy is not available.

In a group of cats treated with surgery alone (historical controls) compared with cats treated with surgery and chemotherapy (doxorubicin or liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin), the median disease-free interval increased from 93 days to 388 days.8

Chemotherapy has been studied in cats treated with both surgery and radiation therapy with inconsistent results. To date, no prospective clinical trials have fully evaluated the role of chemotherapy in multimodal treatment.

Closing RemarksOverall, the results for treatment of ISS are disappointing. Local control is difficult to achieve, with the best results incorporating a combination of aggressive surgery and radiation therapy. The role of chemotherapy is undefined. The most important aspects of treatment for good results are early identification of disease and advanced imaging and surgery at a referral institution. Current research is focused on immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

Location, Location, LocationThe Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force (VAFSTF) recommends the following locations for vaccine administration in cats1,3:

Rabies vaccine: right rear limb, as distal as possible

FeLV vaccine: left rear limb, as distal as possible

3-in-1 feline panleukopenia, herpesvirus 1, calicivirus vaccine: right shoulder

3-2-1 BiopsyThe Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force (VAFSTF) recommends obtaining a biopsy specimen of a mass located at the site of a vaccine or injection based on the 3-2-1 rule:

3—If the mass has been present for longer than 3 months

2—If the mass is wider than 2 cm in diameter

1—If the mass increases in size after 1 month

All of these tumors are locally aggressive and invasion into surrounding tissues is considerably extensive. Early intervention offers the best results.

Future PerspectivesImmunotherapy using recombinant feline interferon-W is safe and well tolerated when injected intratumorally, both pre- and postoperatively.10 However, efficacy has not yet been determined. Other studies using ISS cell lines have found that vincristine and paclitaxel are efficacious in decreasing cell viability in culture.11In addition, imatinib, which inhibits platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and other receptor tyrosine kinases, reverses the protective effect of PDGFR on ISS cell lines and increases their chemosensitivity.12 At this time, no studies have been completed in cats with ISS to determine the efficacy of these treatments.

ISS = injection-site sarcoma, PDGFR = platelet-derived growth factor receptor, VAFSTF = Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force

Related articles:Pain Management in CatsFractionated Radiotherapy—Effective for Sarcomas?Diagnosis & Management of Canine Mast Cell Tumors

FELINE INJECTION-SITE SARCOMA • Sandra Axiak

References

1. Feline injection site sarcoma: Past, present, and future perspectives. Martano M, Morello E, Buracco P. The Vet J 188:136-141, 2011.2. Prognosis for presumed feline-vaccine associated sarcoma after excision: 61 cases (1986-1996). Hershey AE, Sorenmo KU, Hendrick MJ, et al. JAVMA 216:58-61, 2000.3. Diagnosis and treatment of suspected sarcomas. Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force guidelines. JAVMA 214:1745, 1999.

Feline vaccine-associated sarcomas. McEntee MC, Page RL. J Vet Intern Med 15:176-182, 2001.5. Radiation therapy and surgery for fibrosarcoma in 33 cats. Cronin K, Page RL, Spodnick G, et al. Vet Radiog Ultrasound 39:51-56, 1998.6. Preoperative radiotherapy for vaccine associated sarcoma in 92 cats. Kobayashi T, Hauck M, Dodge R, et al. Vet Radiog Ultrasound 43:473-779, 2002.7. A retrospective analysis of radiation therapy for the treatment of feline vaccine-associated sarcoma. Eckstein C, Guscetti F, Roos M, et al. Vet Comp Oncol 7:54-68, 2009.8. Liposome encapsulated doxorubicin (Doxil) and doxorubicin in the treatment of vaccine associated sarcoma in cats. Poirier VJ, Thamm DH, Kurzman ID, et al. J Vet Intern Med 16:726-731, 2002.9. Results of a phase II clinical trial on the use of ifosfamide for treatment of cats with vaccine associated sarcomas. Am J Vet Res 67:517-523, 2006.

Adjuvant immunotherapy of feline fibrosarcoma with recombinant feline interferon-W. Hampel V, Schwarz B, Kempf C, et al. J Vet Intern Med 21:1340-1346, 2007.11. Evaluation of in vitro chemosensitivity of vaccine-associated feline sarcoma cell lines to vincristine and paclitaxel. Banerji N, Klausner J, et al. Am J Vet Res 63:728-732, 2002.12. Imatinib mesylate inhibits platelet-derived growth factor activity and increases chemosensitivity in feline vaccine associated sarcoma. Katayama R, Huelsmeyer MK, Marr AK, et al. Cancer Chemother Pharmaco__l 54:25-33, 2004.