Conducting a Behavior Triage

Routine wellness visits generally do not allow time for comprehensive behavior assessment and treatment plans; however, behavior issues noted during wellness visits may warrant attention and necessitate a plan for next steps. A behavior triage can be quickly conducted by collecting patient history, ruling out medical causes, providing advice for patient and pet owner safety, providing tips on reducing patient stress, and referring to a behavior specialist as needed.1

Once the behavior triage is complete, next steps can be appropriately outlined. If needed, a full behavior assessment can be performed and a treatment plan created during an additional, extended in-clinic appointment or by a behavior specialist (ie, veterinary behaviorist, academically trained applied animal behaviorist).

Goals of Behavior Triage

A behavior triage should include asking open-ended questions, determining the need for immediate diagnostics, providing initial advice for safety management (eg, separating a cat from a child in the home) until a more in-depth plan can be made, prescribing immediate-acting medications to treat anxiety as needed, and considering referral options. Problematic behaviors should be categorized as abnormal and require treatment or normal and require behavioral wellness guidance or problem prevention. Categorization can help inform referral recommendations.

Abnormal and unwanted behaviors may overlap. An underlying anxiety or medical disorder may be driving or exacerbating unwanted behaviors (eg, destructive chewing or soiling in cats with separation anxiety).

Unwanted Normal Behaviors

Cats have many unwanted behaviors that are normal, including destructive scratching, destructive chewing, destroying household plants, lounging on kitchen counters, wildlife predation, and ankle biting/chasing. Cats are highly driven to perform species-typical behaviors, and appropriate outlets for these behaviors should be provided. Owners can be referred to a positive-reinforcement–based trainer and provided with appropriate reading materials and handouts.

Abnormal Behaviors

Abnormal behaviors in cats may include, but are not limited to, elimination outside of designated litter boxes, repetitive behaviors (eg, circling, compulsive light or shadow chasing), self-directed destructive behaviors (eg, excessive skin licking, biting), ingestion of nonfood items (ie, pica), generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, and fears and phobias. Abnormal behaviors that require intervention should be addressed in an additional extended appointment.

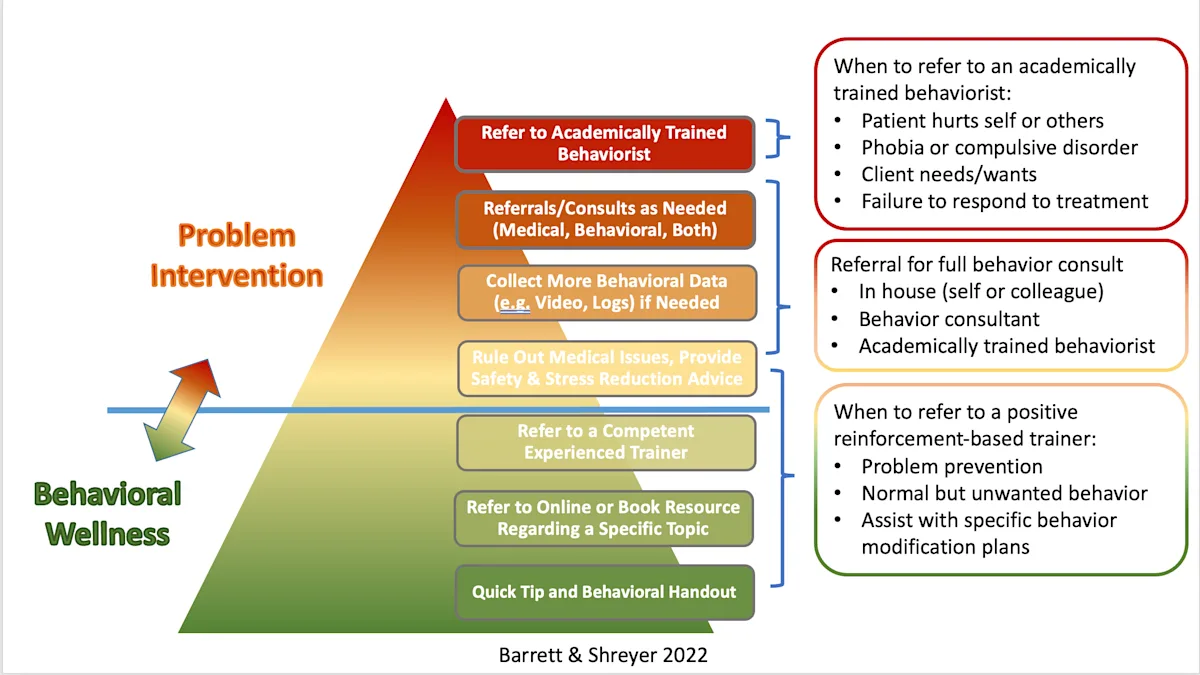

Referral to humane, evidence-based resources for intervention should be tailored to the presented behavior (Figure 1). For example, referral to a behavior specialist may be excessive for a new kitten scratching furniture.1

Overview of how to handle and refer behavior cases. Image courtesy of Traci Shreyer, MA, and Susan Barrett, DVM

Elimination Problems

Careful medical attention should be paid to any cat presented for an undesirable or abnormal elimination pattern, as underlying medical etiologies should be addressed and treated before behavior problems can be managed. Baseline clinical pathology (including CBC, serum chemistry profile, total thyroxine, and urinalysis) is strongly recommended for elimination outside the litter box. Once medical etiologies are ruled out, owner education on litter box management can be provided as a reasonable first step. If there is a sense of urgency and/or if the behavior extends beyond a need for improved litter box hygiene, a separate visit or referral to a behavior specialist may be warranted.

Self-Directed Behaviors

Cats that lick or bite their skin and/or other parts of their body should be evaluated for pruritic skin disease and/or underlying sources of pain or physical discomfort. Most cats presented for self-directed licking have medical etiologies.2 Examination can be extensive but is needed before making a behavioral diagnosis of exclusion. The abnormal behavior should then be addressed at a separate visit and/or through referral to a behavior specialist, as the treatment plan is often complex.

Aggression

Treating patients with aggression can involve an emotional and time burden, as well as greater liability, particularly when injuries to humans have occurred and/or children may be at risk. These patients should be referred to a veterinary behaviorist when possible.

Preparing for an Extended Behavior Assessment & Treatment Plan Appointment

Providing a Behavior & Patient History Questionnaire

Prior to the appointment, owners should complete a behavior and medical history questionnaire to help narrow the focus for the behavior examination and possible diagnostics. Questionnaire forms can be found online (see Suggested Reading) or created and modified. Questions should include information on when and where the cat was obtained, other humans and animals living in the household, indoor and outdoor living environments, household routines, eating and elimination habits, diet, supplements, medications, complete medical history, previous training attempts, and behavior concerns (eg, when the behavior started, frequency).

The questionnaire should also include details on litter box setup, locations, hygiene, and use. History of aggression can be solicited by asking for descriptions of all situations that have triggered hissing, swatting, scratching, or biting, as well as the targets of aggression. Situations, humans, animals, or objects that frighten or provoke anxiety can be investigated by asking about the cat’s response to common household occurrences (eg, presence of visitors, sight of outside animals, loud noises or storms, sounds of household appliances).

Owners can be asked to record problem behaviors ahead of the appointment; however, aggressive behavior or behaviors with potential for harm should not be triggered in order to obtain a video.

Creating Behavior Problem & Differential Diagnosis Lists

A list of medical and behavior problems can be created based on information provided in the questionnaire to determine differential diagnoses. Behavior problems can include those identified by the clinican or by both the clinician and owner but not by the owner alone. For example, use of a spray bottle to stop a cat from urinating outside the litter box may not be identified by the owner but should be considered a problem. Behaviors should be considered objectively, without motivations or pre-emptive diagnoses. For example, when an owner insists their cat urinates on the bed to express anger for being left with a pet sitter, the problem may be listed as cat urinates a large volume on soft, horizontal surfaces when the owner is away on vacation.

A more definitive list of differential diagnoses, including behavior and medical causes, can be created once the oral history is collected and medical diagnostics are completed. For example, differentials for patients urinating when owners are away may include litter box aversion, separation anxiety, anxiety-related urination, and feline interstitial cystitis.

Conducting a Behavior Examination

Entering the Clinic

The owner should be asked to wait outside the clinic, preferably in a car, with the patient until it is time for the behavior examination. Inside the clinic, the patient should be kept separate from other owners and patients. White noise can be used if a quiet space is difficult to locate.

Hiding and perching options should be available in the examination space. The ability to feel concealed can substantially reduce stress in cats. Cats should be permitted to remain in their carrier, if desired, until a more in-depth physical assessment is needed. High-value treats (see Ladder of Treats) and long-lasting enrichment options (eg, interactive food-dispensing toys) can be used to keep cats content and occupied. Food sensitivities, allergies, and preferences should be determined before giving food or treats to build trust, provide enrichment, and determine reward preferences.

LADDER OF TREATS*

Hypoallergenic kibble

Dry treats

Soft, meaty treats

Canned cat food

Bits of tuna or chicken

Cheese spread

Lickable pastes

Lickable pastes

*Ranked from lowest to highest value

Asking Follow-Up Questions

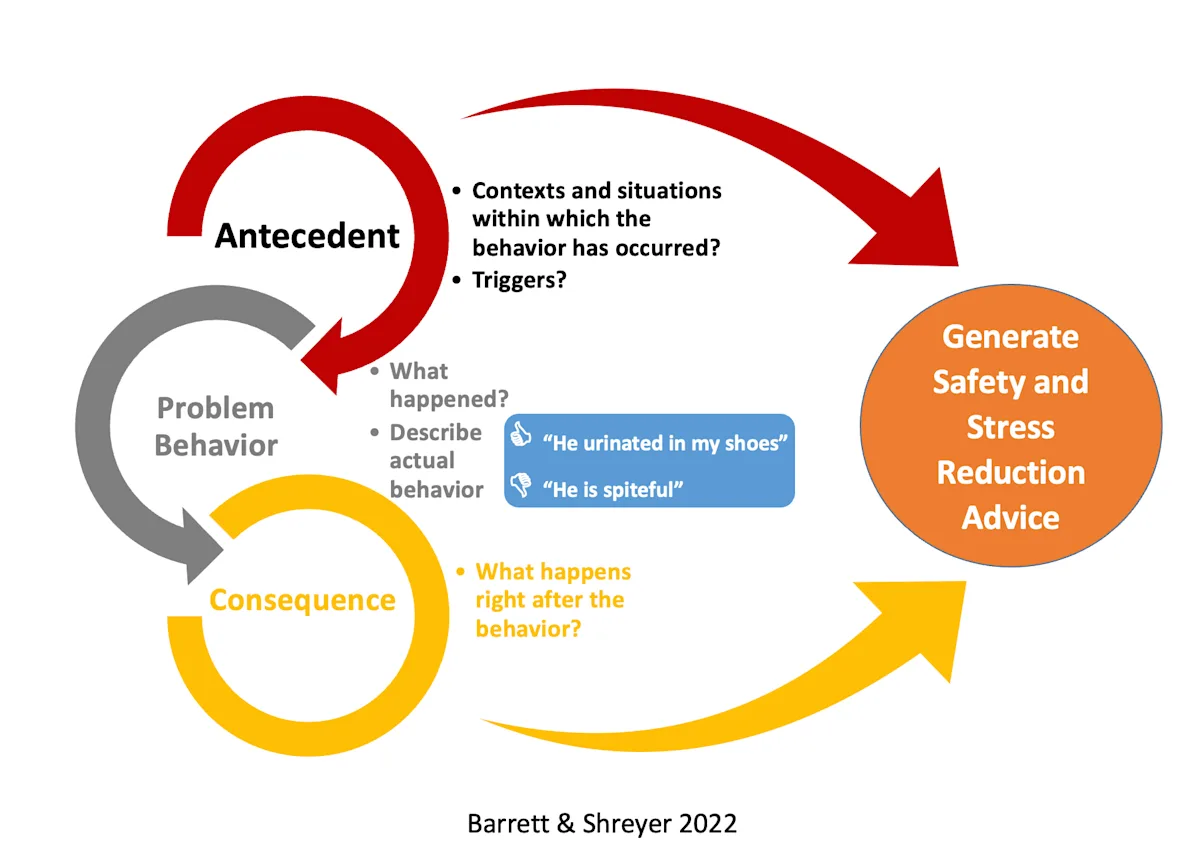

In addition to the questionnaire, owners should be asked open-ended questions to clarify patient history and help finalize the differential diagnosis list. The antecedent–behavior–consequence (ABC) applied behavior analysis approach (Figure 2) to taking patient history can be used to better understand motivations behind unwanted behaviors.3

The ABC applied behavior analysis can help identify triggers and generate advice on safety and stress reduction. Antecedent (ie, trigger) occurs before the behavior, behavior (ie, problem behavior) is the reaction to the antecedent, and consequence (ie, owner reaction, reinforcement) happens immediately after the behavior and may be seen as the apparent result of the behavior. Image courtesy of Traci Shreyer, MA, and Susan Barrett, DVM

For example, although many owners are surprised by seemingly sudden aggressive behavior and report the behavior as unprovoked, most incidents of aggression have a trigger. The ABC applied behavior analysis can help identify these triggers, work through possible owner misjudgments, and create safety and management strategies to help avoid provoking aggressive behaviors.

Ruling Out Medical Etiologies for Unwanted Behaviors

If not performed during the behavior triage, additional diagnostic testing should be performed as indicated, including a complete physical examination, CBC, serum chemistry profile, total thyroxine testing, urinalysis, and imaging.4 For example, a cat presented for defecating next to the litter box should be evaluated for evidence of pain as a result of constipation and pelvic or lumbar osteoarthritis; abdominal and/or pelvic and lumbar radiography may also be indicated.

Establishing a Treatment Plan

In-person questions can provide information for a more definitive diagnosis list, from which a treatment plan can be established. Primary aspects of the plan should cover introduction of safety and management strategies, implementation of environmental modification, initiation of behavior modification and training, and creation of a plan to reduce anxiety. Although a tentative treatment plan may be considered based on the patient history questionnaire, changes should be made based on additional information and behaviors demonstrated on examination. Patients can appear better or worse on paper than in the clinic; therefore, flexibility in making changes during the behavior examination is essential.

Safety & Management Strategies

A plan to avoid triggers identified via ABC applied behavior analysis should be implemented until the response can be modified. A practical solution can be suggested for each trigger. If a trigger cannot be avoided and humans or animals in the home are at risk for injury, referral to a behavior specialist and discussion regarding relinquishment or euthanasia should be considered.

Safety and management strategies can be straightforward. For example, for a cat that bites and swats when petted by visitors to the home, visitors should be instructed to avoid petting the cat. In cases in which this is not possible, the cat can be confined to a safe room and provided necessary resources.

Behavioral euthanasia conversations are difficult and should be approached with compassion and care. Mentioning behavioral euthanasia as an option often helps owners feel they are permitted to talk about or consider it in future if the management plan does not adequately reduce safety risks.

Environmental Modification

Changes to the indoor and/or outdoor environment can be implemented for safety and/or stress reduction. In cats with inappropriate elimination behaviors, increasing the size of litter boxes, adding additional litter boxes, and increasing frequency of litter box cleaning should be considered. For example, for a cat that urinates next to the litter box when the litter box is dirty, owners should be instructed to scoop the box at least once daily.

Additional resource stations to meet environmental needs can be added to reduce social tension in cats sharing a household, and high peripheral vantage points can be installed to provide cats with a sense of safety. Basic behavioral needs should be met, with ample options for hunting/play behaviors, chewing and scratching, and comfortable, elevated viewing. When educating owners about environmental needs, the phrase Hunting–Chewing–Scratching–Viewing can be helpful and easy to remember.

Behavior Modification & Training

Behavior modification should be tailored to each patient. Emotional modification should be the focus for some patients (eg, those with aggression issues), but others may need training in which new, desirable behaviors take the place of current, unwanted ones. Training patients with severe generalized anxiety may be difficult or impossible without adequate anxiety relief, and training may need to be delayed until the anxiety reduction plan takes effect (see Reducing Anxiety).

Counterconditioning and positive-reinforcement training (ie, training via positive reinforcement of desirable behaviors) are some of the main tenets of behavior modification.

Counterconditioning

Counterconditioning is a form of Pavlovian (ie, classical) conditioning whereby a negative emotional response becomes a positive emotional response through repeated pairing of a trigger with a reward. With repetition, the trigger evokes a positive response, thus decreasing motivation to exhibit the initial fear-induced behavior. For example, if a cat fearfully hisses and swats at visitors entering the home, counterconditioning may involve asking visitors to give high-value treats each time they enter the house. Repetition teaches association of visitors entering with a reward and, over time, lessens fear and reduces hissing and swatting behaviors.

Response Substitution

Response substitution (ie, training desirable behaviors incompatible with the problem behavior) may be beneficial as part of a behavior modification plan. A cat that hisses and swats at visitors may be trained to go to a perch away from the front door when there is a knock at the door or the doorbell rings, allowing the cat to retreat to a safe location and avoid an altercation with humans who may trigger fear.

Reducing Anxiety

Known fear, anxiety, and/or reactivity triggers should be avoided when possible.

For cats with mild to moderate behavior problems, products containing synthetic cat pheromones and/or nutraceutical products (eg, L-theanine, milk proteins, probiotic supplements) can be recommended. In moderately severe or severe cases, psychopharmacology is likely indicated; however, there are currently no FDA-approved medications for treatment of behavior problems in cats.

Reducing stress and anxiety should always be included in a behavior plan, as stress commonly contributes to behavior problems in cats. Medication alone is unlikely to affect significant change and should be used alongside behavior and environmental modification; however, stressed and anxious patients may struggle to learn new behaviors and have decreased response to behavior modification strategies without medication.

Follow Up & Monitoring

Behavior problems can be emotionally taxing, and an extended appointment can be inconvenient5; however, gaining the owner’s support of the plan, particularly regarding psychotropic medications, is critical for success. The owner may need time to consider the plan, especially when medications are involved. Ensuring they are comfortable and part of the decision-making process can increase compliance.

A staff member should follow up 5 to 7 days (1-2 days if medication is prescribed) after the appointment to encourage cooperation with management, medication, and behavior modification. Following up is critical to ensure correct dosages are given and confirm there are no adverse effects. Cats can be particularly sensitive to the anticholinergic effects of some drug classes. Confirming normal elimination patterns is important so functional urine blockage or constipation can be addressed immediately. A recheck may be scheduled in 6 to 8 weeks to allow time to gauge the effectiveness of the plan and make adjustments as needed.