Facial Nerve Paralysis

Mark Troxel, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology), Massachusetts Veterinary Referral Hospital, Woburn, Massachusetts

Facial nerve paresis or paralysis is relatively common in veterinary neurology. The most common cause is idiopathic facial nerve paralysis, which accounts for approximately three-fourths of all cases.1,2 Other differential diagnoses include otitis media, idiopathic cranial polyneuropathy, hypothyroidism, trauma, and other less common causes (Table 1).3-20

Table 1: Differential Diagnoses for Facial Paralysis

Neuroanatomy

The facial nerve is a mixed (ie, motor and sensory) cranial nerve (VII) that originates in the medulla oblongata. It exits the brainstem caudolaterally through the trapezoid body, exiting caudal to the trigeminal nerve (V) and cranial to the vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII). The nerve passes through the internal acoustic meatus with the vestibulocochlear nerve and enters the facial canal in the temporal bone. Here the facial nerve is separated from the tympanic bulla by only a simple squamous epithelial layer and loose connective tissue. The facial nerve exits the skull through the stylomastoid foramen and divides into multiple branches that innervate multiple structures of the head, including all facial expression muscles, the taste buds of the rostral two-thirds of the tongue, and the lacrimal gland. (See Table 2 for complete list of innervated structures.)21,22

Table 2: Facial Nerve Innervation22

GSA = general somatic afferent, GSE = general somatic efferent, GVA = general visceral afferent, GVE = general visceral efferent, SVA = special visceral afferent

Signalment

Facial nerve paralysis is most common in middle-aged and older dogs.1 Although any dog breed can be affected, cocker spaniels are overrepresented for idiopathic facial paralysis.1,7 This breed is also predisposed to otitis media and hypothyroidism.5,7

Clinical Signs & Neurologic Examination

Most dogs are presented for evaluation after owners notice lip and/or ear droop, excessive drooling, food retention in the lips, or food falling out of the mouth (Figure 1). Patients most commonly have unilateral facial nerve paralysis, but bilateral disease may occur.23

Left facial paralysis in an English setter with idiopathic facial nerve paralysis. Note the left facial droop, excessive salivation from the left side of the mouth, and slight deviation of the nasal philtrum to the right. Neurologic examination also revealed absent menace response and palpebral reflex in the left eye, absent lip retraction when pinched, and decreased sensation inside the left pinna.

Facial nerve paralysis causes ipsilateral absent menace response, lip droop, ear droop, hypersalivation on the side with facial droop, deviation of the nasal philtrum toward the normal side, inability to voluntarily blink, absent palpebral reflex, and absent lip contraction. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and corneal ulceration may be present if the parasympathetic branches of the facial nerve that innervate the lacrimal glands are also affected.

Diagnosis

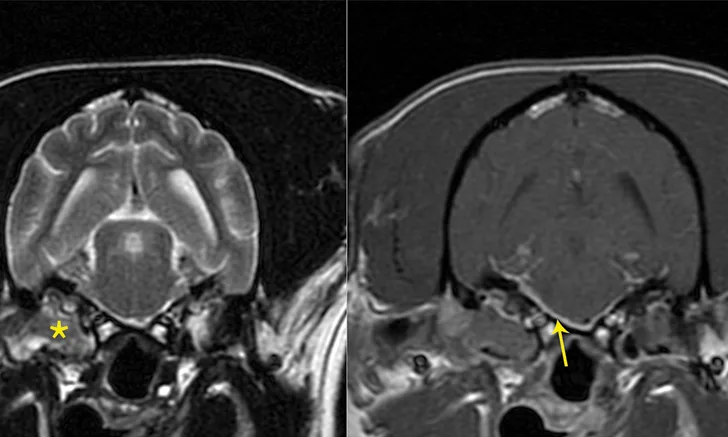

Diagnosis of idiopathic facial nerve paralysis is typically based on neurologic examination and exclusion of other potential causes. The minimum database for facial paralysis is a CBC, serum chemistry panel, and thyroid hormone level. A Schirmer tear test and otoscopy should be performed on all patients with facial nerve paralysis. Fluorescein staining should be performed if decreased tear production is identified on Schirmer tear test or there are any signs of corneal disease suggestive of corneal ulceration. Advanced imaging (eg, MRI, CT) is recommended to rule out structural disease, especially if there are clinical signs or neurologic examination findings suggestive of middle ear disease, multiple cranial nerve involvement, or brain stem dysfunction (Figure 2).24,25

Transverse T2-weighted (left) and post-contrast T1-weighted (right) images obtained from a cockapoo with sudden onset of right peripheral vestibular dysfunction and right-sided facial paralysis. MRI showed right (*) worse than left middle ear disease with extension into the calvarium (otogenic meningitis; arrow) and into the right horizontal ear canal. Neutrophilic pleocytosis was present in the CSF (no bacteria seen on direct examination; CSF culture negative). The patient was treated with oral clindamycin for 1 month to reduce the intracranial portion of infection, and then right total ear canal ablation and lateral bulla osteotomy was performed. The histologic diagnosis for the tissue in the tympanic bulla was cholesteatoma, and bacterial culture identified secondary Staphylococcus pseudintermedius infection. The antibiotic was changed to amoxicillin-clavulanate based on antibiotic sensitivity testing.

Treatment

Treatment is largely supportive for idiopathic facial paralysis (eg, artificial tears to lubricate the cornea, nutritional support). Long-term (potentially life-long) treatment with artificial tears is recommended to keep the cornea lubricated even if tear production is normal. This reduces the risk for exposure keratitis and corneal ulceration secondary to inability to blink.

Corticosteroid use is controversial and has not been clearly proven to improve or hasten recovery in veterinary patients. Studies in human medicine have shown some efficacy in patients with Bell’s palsy, a clinically similar disorder, but it is still unclear if idiopathic facial paralysis has an inflammatory component in dogs and cats. Acupuncture has been reported as a treatment for idiopathic facial paralysis.26

In general, the underlying cause of facial nerve paralysis, if identified, should be specifically treated. Thyroid hormone supplementation is recommended for hypothyroid patients, but it may take weeks to months for neurologic signs to resolve with thyroid hormone supplementation. Owners should be counseled that facial paralysis may not resolve even after the patient becomes euthyroid.5 Long-term antibiotics (6-8 weeks), deep ear flush, or bulla osteotomy may be required in patients with otitis media.

Prognosis

The prognosis for full recovery is guarded-to-poor, regardless of underlying cause or success of treatment. Recovery may take weeks to months. Patients often experience partial recovery. If the patient has unilateral facial paralysis, the client should be counseled that the other side of the face may become affected within a matter of days to weeks.

Editor's note: This article was originally published in April 2016 as "Facial Nerve Paralysis."