Elevating the Role of Veterinary Nurses

Kenichiro Yagi, RVT, VTS (ECC, SAIM), Adobe Animal Hospital, Los Altos, California

The question What do veterinary nurses do? is at the forefront of many veterinary professionals’ minds in light of the Veterinary Nurse Initiative that aims to standardize the profession’s educational requirements, scope of practice, requirements to maintain the credential, and title protection, and to rename the role from veterinary technician to veterinary nurse.1 The veterinary technician/nursing profession has consistently redefined itself over its history, and the veterinary nurse role is vastly different today than the animal technician position that emerged more than 50 years ago.

So, in this—what seems to be—ever-changing role, what can veterinary nurses do for the practice, and how can the practice and the profession utilize their vast skillset to elevate the nursing role to its fullest potential?

Elevating the Role in Practice

The Veterinary Practice Act

The scope of a veterinary technician’s practice is legally defined by each state’s veterinary practice act and administrative rules. In general, the tasks of providing a diagnosis and prognosis, prescribing medications, and performing surgery are limited to licensed veterinarians. Any other veterinary medicine tasks can be performed by a veterinary technician or noncredentialed assistant under varying degrees of veterinarian supervision, with the veterinarian assuming responsibility.

In some states, credentialed veterinary technicians are permitted to perform specific tasks noncredentialed assistants are not. (See Resource.) Examples of commonly regulated tasks include inducing and administering anesthesia; splinting, casting, or bandaging limbs; and suturing existing skin wounds. Having veterinary technicians perform these tasks improves team efficiency, which leads to better patient care and practice profitability while also contributing to job fulfillment and higher team member retention.

A survey evaluating the financial impact of hiring credentialed veterinary technicians reported an average annual practice revenue increase of $93 311 for each credentialed veterinary technician in the practice.2

Utilization Depends on Competence & Trust

The supervising veterinarian is responsible for the outcome of any task performed within the practice; therefore, whether veterinary nurses perform these tasks depends on the veterinarian–veterinary nurse trusting relationship that has developed through the veterinarian witnessing the veterinary nurse’s competence. Trusted veterinary nurses can perform a variety of tasks—from routine (eg, restraining; drawing blood; obtaining temperature, pulse rate, and respiratory rate) to sophisticated (eg, anesthesia induction, placement of central lines or nasoenteral tubes, performing thoracocentesis, mechanical ventilation application).

Certification processes to become a veterinary technician specialist (VTS) in 1 of 15 areas of expertise have been established over the past 20 years, giving veterinary nurses more opportunities to demonstrate competence and more career path choices. (See NAVTA-Recognized Veterinary Technician Specialties.) Regardless of credentials or specialty, the veterinarian–veterinary nurse trusting relationship developed through consistent and successful displays of skill, knowledge, communication, and dedication correlates with higher degrees of utilization.

NAVTA-Recognized Veterinary Technician Specialties

Competence & Trust Lead to Autonomy

In addition to performing specific tasks, veterinary nurses play a large role in patient advocacy—that is, being the voice of the patients. A veterinary nurse can apply knowledge and understanding of animal physiology and behavior, nursing care, and other disciplines to influence a more positive patient outcome.

A practice that utilizes veterinary nurses at the highest level can empower them with autonomy. For example, in some practices, moment-to-moment patient assessments and treatments for in-patients are entrusted to veterinary nurses, with veterinarians making only routine rounds or being contacted as needs arise. For example:

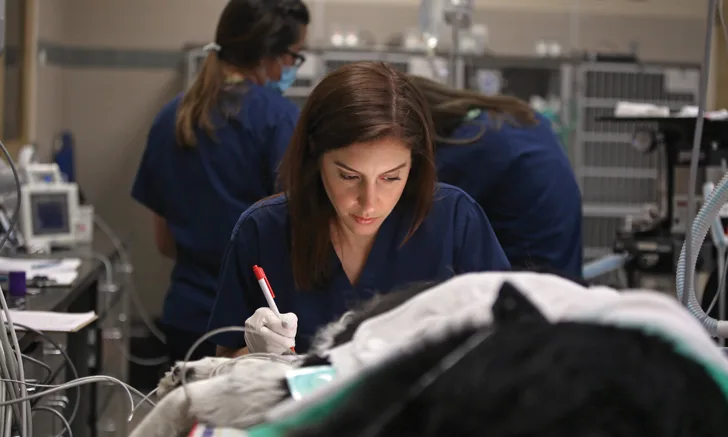

Veterinary nurses are given the ability to tailor patient care within prescribed treatments (eg, adjusting constant-rate infusion [CRI] for pain control, maintaining patient blood pressure and perfusion by adjusting vasopressor CRIs and fluid infusions based on monitoring and assessment of patient status; see Figure 1).

Veterinary nurses serving as anesthetists can be entrusted with formulating an anesthetic plan appropriate for the individual patient. The veterinarian then approves the plan, and the veterinary nurse adjusts the anesthetic dosages and IV fluids during the procedure to ensure an adequate anesthesia plane while optimizing cardiovascular function.

The best practices formulate treatment plans with both veterinarians and veterinary nurses.

April Smeraldo, RVT, assesses a patient’s cardiovascular status through auscultation of the heart, pulse palpation, and ECG. Figures courtesy of Kenichiro Yagi, MS, RVT, VTS (ECC, SAIM), and NAVTA

Veterinary Nurses & Leadership

In the Practice

Leadership comes from all practice levels.

In clinical settings, veterinary nurses can demonstrate leadership by organizing efficient workflows on the hospital floor. For instance, when a patient goes into cardiopulmonary arrest, a veterinary nurse can serve as CPR team leader and facilitate independent team functions to resuscitate the patient and allow the veterinarian to focus on determining diagnosis and treatment of the inciting cause and communicating with the client.

Veterinary nurses can also demonstrate leadership by taking ownership of training new team members, establishing nursing protocols based on current published evidence, and developing training programs to help others reach their next career step. (See Figure 2.) Many veterinary nurses choose to share their knowledge by lecturing, authoring articles and textbooks, and mentoring the future generation. Any veterinary team member who looks to help others develop their skills and reach their goals can be a personal leader.

Robyn Baillif, RVT, VTS (ECC), discusses patient monitoring during an in-house training session to elevate the skill level of team members.

Beyond the Practice Walls

For veterinary nurses—or any team member, for that matter—leadership does not stop within the practice walls. Veterinary nurses can pursue leadership opportunities by serving the profession as members of veterinary medical boards, veterinary medical associations, or veterinary technician associations at national or state levels, and by working to elevate and promote the profession by calling for legislative changes that enhance public protection. Being involved in committees or running for elected board positions are also displays of leadership that can elevate and promote the nursing profession.

National leaders in the profession gathered at the NAVTA Veterinary Technician Leadership Summit in January 2017 to discuss profession-wide issues.

Shaping the Future of the Profession

Veterinary nurses who pursue new heights in the practice or contribute to organized veterinary medicine are important in shaping the future by defining the profession and advocating for positive change. The veterinary nursing profession has evolved over more than 50 years and created a heightened awareness and interconnectivity of individuals throughout the world. (See Figure 3.) Every member of the veterinary nursing profession can make a difference by pursuing new limits and taking ownership of his or her path.