Corneal & Conjunctival Cytology

Leah Moody, BSc, Mississippi State University

Caroline Betbeze, DVM, MS, DACVO, Mississippi State University

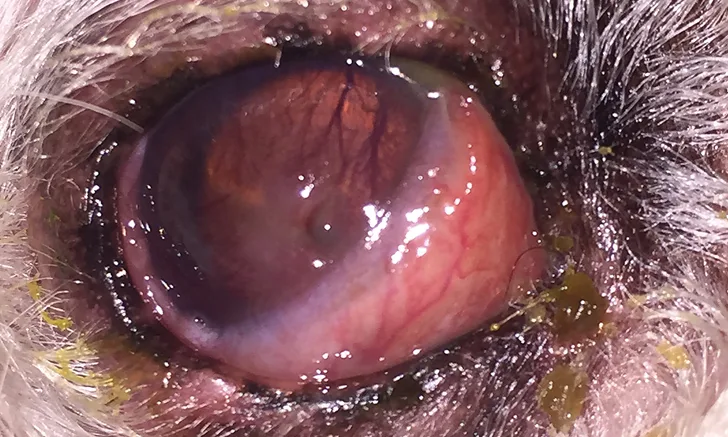

Mucopurulent ocular discharge, hyperemic conjunctiva, and elevation of the nictitating membrane in a dog. Signs of stromal ulcerative keratitis, including an obvious corneal defect and superficial corneal vascularization and cellular infiltration of the axial cornea, are present. Corneal and conjunctival cytology were performed.

An initial ocular examination with basic diagnostic testing (eg, direct and indirect ophthalmoscopy, fluorescein stain, Schirmer tear test, tonometry) is indicated for most patients presented with corneal and/or conjunctival diseases, which are common in domestic animals. Ulcerative keratitis (Figure 1) is particularly common and often resolves in 5 to 7 days with appropriate treatment.1 With complicated corneal ulcers and other progressive or persistent corneal diseases, investigation beyond basic diagnostics may be necessary.

Cytology can have a variety of applications, including:

Immediate characterization of inflammatory or neoplastic cells or infectious organisms, including cases in which culture and susceptibility testing or PCR may be indicated

Allowing for direction of empiric therapy while awaiting culture and susceptibility results

Diagnosing many infectious and inflammatory diseases (eg, ulcerative or fungal keratitis, feline eosinophilic conjunctivitis or keratitis, bacterial conjunctivitis)

Facilitating prompt and appropriate medical therapy <sup 2sup>

Characterizing cells of a proliferative corneal or conjunctival mass

In patients with corneal ulcers that are progressing in depth or do not respond to initial treatment within 5 to 7 days because a common cause of progression is infection3

Corneal cytology is contraindicated in patients that have severe ulcers with an exposed Descemet’s membrane (ie, descemetocele) or with corneal perforation. Because these patients require surgical treatment, cytology is unnecessary and could cause further injury to the eye.1,3 Conjunctival cytology is rarely contraindicated; however, it may not be of much diagnostic value in patients with conjunctival lesions without an ulcerated or easily exfoliated surface. Cases in which conjunctival cytology may not be diagnostic include conjunctival thickening or nodules (eg, nodular granulomatous episcleritis), certain infectious organisms (eg, mycobacterial, fungal), and some types of neoplasia (eg, squamous cell carcinoma).4 In addition, conjunctival cytology, although not contraindicated, has minimal diagnostic utility in corneal ulceration.

Culture and susceptibility testing can be performed in combination with cytology if bacterial or fungal disease is suspected. If both procedures will be performed, culture samples should be taken before cytology collection.3,4

Microscopic evaluation of the corneal cytology sample collected from the patient in Figure 1 revealed moderate neutrophilic inflammation and squamous epithelial cells. No infectious agents were found; however, neutrophilic inflammation supports the diagnosis of infectious keratitis.

Corneal or conjunctival cytology can be used to identify the number, morphology, and staining characteristics of inflammatory cells and infectious organisms present in the disease. Neoplastic cells may also be identified in the sample.4 Normal corneal samples should include noncornified epithelial cells, few lymphocytes and neutrophils, and rare bacteria; moderate neutrophilic inflammation can be identified in keratitis cases, including ulcerative keratitis (Figure 2).5 Conjunctival samples are normally composed of squamous and columnar epithelial cells, goblet cells, melanin, and occasional bacteria; inflammatory cells can be visualized in conjunctivitis cases (Figure 3). Lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, and plasma cells are rarely observed.

Microscopic evaluation of the conjunctival cytology sample collected from the patient in Figure 1 also revealed neutrophilic inflammation with no infectious agents, which indicates secondary conjunctivitis.

With bacterial disease, neutrophils predominate, may be degenerate or nondegenerate, and may contain intracellular bacteria. Even if bacteria are not visualized, presence of neutrophilic inflammation suggests infection of the cornea.1 Identification of fungal hyphae is suggestive of mycotic disease.3 Presence of eosinophils or mast cells is an abnormal finding in a corneal or conjunctival cytology sample and is suggestive of eosinophilic keratitis or allergic conjunctivitis, respectively.4,6

Successful treatment of corneal and conjunctival disease requires appropriate and immediate therapy, as vision loss can occur rapidly.3 Referral to an ophthalmologist should be considered for patients with complicated corneal ulcers and other progressive ocular diseases.

Step-by-Step: Corneal & Conjunctival Cytology

What You Will Need

Topical anesthetic (eg, proparacaine, tetracaine)

Glass slides

Kimura spatula

#15 scalpel blade (sterile)

Microapplicator to collect cytology

Romanowsky-type stain

Microscope

Step 1

Using a damp cotton ball or piece of ocular gauze, gently wipe away any ocular surface debris, mucus, or excess ointment. Traditional 4-by-4 (10.16 cm x 10.16 cm) gauze may be used to clear periocular debris but should never come in contact with the corneal or conjunctival surface.

Step 2

Apply 1 to 2 drops of topical anesthetic to the eye, waiting approximately 30 seconds between each drop. Allow approximately 5 minutes for the topical anesthetic to achieve maximal effect; cytology supplies can be collected during this time.

Author Insight

Most patients require only topical anesthesia, and sedation is not usually necessary; however, fractious or excited patients may require chemical sedation to reduce the risk for injury during the procedure. If required, sedation may cause the globe to rotate ventrally, and small-toothed forceps (eg, Bishop-Harmon) will be needed to gently grasp the bulbar conjunctiva to position the globe for cytology collection.

Step 3

Restrain or have an assistant properly restrain the patient by placing one hand on the back of the head and the other hand under the chin, being careful not to squeeze the muzzle too tightly.

Hold the eyelids open using the thumb and forefinger of the nondominant hand. Rest the dominant hand on the patient’s head. This position will ensure that, if the patient moves, the instruments move with the patient, which can decrease the chance of ocular injury. Be careful not to touch the eyelids with the instrument, as this may contaminate the sample.

Step 4

Using a microapplicator, Kimura spatula, or the blunt end of a sterile #15 scalpel blade, gently scrape the cornea or conjunctiva 5 to 7 times. The scraping movement can be up to 3 to 5 mm in length, depending on the size of the area of cellular infiltration. For the cornea, sampling the area surrounding the ulceration or any area that has a cellular appearance is recommended (A). For conjunctiva (palpebral or bulbar), any diseased tissue should suffice (B). An ideal sample is collected with minimal patient discomfort and provides an adequate monolayer of intact corneal or conjunctival epithelial cells.

Author Insight

The margin of the ulcerative defect, plaque, or raised inflammatory lesions will have the highest chance of containing causative organisms, inflammatory infiltrate, or diagnostic cells.

Step 5

Transfer the sample from the collection instrument to a glass slide by gently tapping the instrument or rolling the brush on the slide, being careful not to smear or crush the cells. Preparing several slides from repeat sampling and multiple samples can increase the chances of collecting an adequate diagnostic sample, but the risks of collecting more than one sample must be evaluated based on the severity and depth of the lesion.

Step 6

Stain the slides using a Romanowsky-type stain (eg, Diff-Quik) and Gram stain. Slides can also be submitted to a diagnostic laboratory that is familiar with veterinary ophthalmologic diseases. The authors suggest evaluating at least one slide in-house to quickly initiate proper patient therapy.

Step 7

Evaluate a sample under oil immersion using a microscope, ensuring evaluation of multiple high-power fields.