Chronic Ulcerative Paradental Stomatitis of Dogs

Jan Bellows, DVM, FAVD, DAVDC, DABVP, All Pets Dental, Weston, Florida

Chronic ulcerative paradental stomatitis (CUPS)—also known as ulcerative stomatitis, idiopathic stomatitis, lymphocytic plasmacytic stomatitis, and plaquereactive stomatitis—is a painful and often debilitating disease involving mucosal areas that contact plaque and calculus in predisposed dogs.

Related Article: Feline Stomatitis

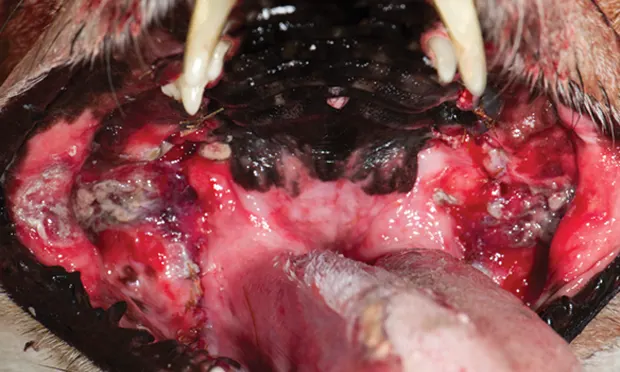

Marked labial inflammation with granuloma formation secondary to plaque mucosal contact against the left maxillary canine and third incisor.

Paradental refers to the mucous membranes on the inside of the lips and cheeks, palate, and tongue.1 The inflammatory lesions do not include the teeth and rarely include the attached gingiva unless accompanied by periodontal disease. The syndrome’s appearance results in the term kissing lesions because the injuries are located where the oral mucous membranes rub against the plaque and calculus-laden teeth (Figure 1).2

Related Article: Dental Radiography

Contact mucositis with ulceration secondary to plaque and tartar-laden maxillary incisors, canines, premolars, and molars.

Additional Terminology

Because the syndrome affects companion animals, is usually not chronic or ulcerative, and rarely affects the entire mouth, it was given the name contact mucositis and contact mucosal ulceration by the American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC) in 2013.3 The AVDC concluded:

Contact mucositis and contact mucosal ulceration are lesions in susceptible individuals that are secondary to mucosal contact with a tooth surface bearing the responsible irritant, allergen, or antigen. They have also been called “contact ulcers” and “kissing ulcers.”3

Even the terminology contact mucositis, however, is confusing in companion animal practice. In human dentistry, contact mucositis4 refers to contact with something ingested that inflames the gingiva because of an allergic reaction. In veterinary practice, affected patients (usually dogs) are generally immune-compromised and develop a hyperimmune mucosal response in the tissues that physically touch plaque (Figure 2).1

Swelling, ulceration, and marked inflammation (arrows) of the vestibular mucosa caused by plaque and tartar on the maxillary cheek teeth.

Related Article: Nerve Blocks for Oral Surgery in Dogs

Examination and Progression

Histopathological examination of lesions should show a population of lymphocytes and plasmacytes, confirming that the syndrome is inflammatory rather than infectious.1 The antigens in bacterial plaque are theorized to be the stimulants.1

At syndrome onset, gingivitis is usually present around the teeth that touch the inflamed alveolar mucosa. If untreated, the gingivitis often progresses to periodontal disease. Areas of gingival recession with root exposure appear to be more prevalent in these cases, exacerbating inflammation and pain.

Examination is often difficult without general anesthesia; most affected patients experience significant pain on manipulation of the oral mucosa. In dogs and cats, the mucosa apical to the maxillary canines and fourth premolars are the most likely to be involved.4 They exhibit marked inflammation with or without ulceration and necrosis. In general, the vestibular mucosa in areas that contact tooth surfaces are also affected (Figure 3).

Breeds Prone to CUPS

Any dog can be affected by contact mucositis. There may be a genetic predisposition to the syndrome, especially in the Maltese dog, greyhound, Cavalier King Charles spaniel, and the Scottish terrier.<sup4 sup>

Clinical Signs

Signs include marked halitosis; ptyalism with thick, ropy, and occasionally bloody saliva (Figure 4); pain in and around the mouth; and difficulty prehending hard food and chew toys, especially in cases where the lateral mucosal surfaces of the tongue are eroded from contact with lingual mandibular surfaces (Figure 5).

Visual examination findings include inflamed mucosal gingiva where contact is present, ulceration with formation of a pseudomembrane, and mucosal necrosis. At times, the paradental infection is so marked that the necrotic buccal mucosal damage extends through the skin. This is in contrast to periodontal infection that affects the socket holding the tooth—the cementum, periodontal ligament, alveolar bone, and gingiva. Patients may have both contact mucositis and periodontal disease (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 4.

Marked pytalism and gingival inflammation in a Maltese dog affected by contact mucositis.

Mimics and Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be made visually where mucosal lesions lie directly against plaque- and tartar-encrusted exposed tooth root surfaces. Differential diagnoses include azotemia and autoimmune diseases (eg, mucous membrane pemphigoid, systemic lupus erythematosus, bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, epidermolysis bullosa). Histologic examination of a wedge biopsy is generally diagnostic. Autoimmune bullous diseases are characterized by subepithelial clefting. Contact mucositis lesions typically show plasmacytic and lymphocytic infiltrates.

Related Article: Top 5 Oral & Dental Lesions

Treatment

Preoperative testing (eg, CBC, serum chemistry panel, urinalysis) and a thorough oral examination under anesthesia should be pursued. Elevated total protein and neutrophilia are typical findings in CUPS patients. While the patient is under general anesthesia with intubation, a tooth-by-tooth examination should be conducted, including periodontal probing and intraoral radiographs. The teeth should be thoroughly cleaned above and below the gum line and then polished.

Oral examination findings should be discussed with the clients to consider the best way to tailor patient-specific therapy, which often initially or eventually involves multiple extractions and future plaque-control options.

In these patients, even a small amount of plaque can initiate a painful ulcerative inflammatory reaction. Teeth affected by grades 3 and 4 periodontal disease should be extracted.

Either a dental sealant applied at the time of anesthesia that lasts 6 months or a waxy polymer applied weekly is recommended to help decrease plaque accumulation in teeth that have not been extracted. Antibiotics approved for dental infections are not indicated as sole therapy. Contact mucositis, even with ulceration, is considered a primarily inflammatory disease and not infectious.

Other medications that have been used in the past with limited success include pentoxifylline to decrease inflammation.5 Niacinamide may also be helpful. Pain relief is likewise indicated. 5 Pulsed antibiotic therapy (dental-approved antimicrobial administered the first 5 days of each month) is not recommended.2,5 The use of anti-inflammatory medications in control of CUPS may be helpful but is controversial because the cause of the syndrome (plaque and tartar rubbing against the mucosa) is not addressed.2,4

Related Article: Pain Management & Periodontal Disease

Home care, including teeth brushing twice a day to prevent plaque accumulation and extralabel daily application of a plaque gel barrier, may be helpful in controlling mucositis and ulceration.

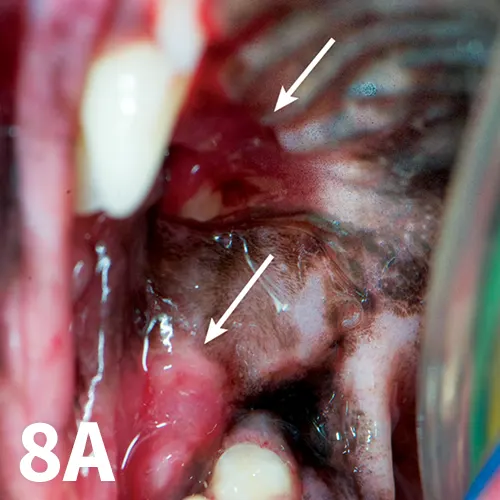

In advanced cases in which the client cannot provide twice-daily plaque control or if such care is not successful, removal of the teeth adjacent to the ulcerated areas or, in some cases, all teeth can result in rapid elimination of inflammation and pain (Figure 8).

The use of the CO2 laser to photovaporize contact mucositis and mucositis with ulceration lesions has met with favorable results when combined with strict plaque control. The laser should be set between 3 to 6 watts in continuous mode. CO2 laser treatment of the exposed ulcer surfaces may be beneficial to lessen patient discomfort and aid healing (Figures 9 and 10).6

Figure 8A.

Selective extractions of caudal cheek teeth prompt a cure (arrows).

CUPS = chronic ulcerative paradental stomatitis