Chronic Cough

Lynelle R. Johnson, DVM, MS, PhD, Diplomate ACVIM, University of California–Davis

A 12-year-old, spayed female terrier mixed-breed dog was presented for chronic cough.

History

The dog had been adopted 1 year previously, and dental prophylaxis was done 6 months after adoption. Ten days after the dental procedure, the dog started coughing a dry, deep cough. The spells would occur at night after she had gone to sleep. The dog was boarded at the local veterinarian 3 months ago and developed nasal and ocular discharge; these signs resolved after treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid at an unknown dose for 7 days. However, the cough persisted. Treatment with prednisone (0.5 mg/kg PO daily for 5 days and every other day for 5 days) also did not resolve the cough. The dog is current on vaccines, is negative for heartworm, and is receiving monthly heartworm preventative.

Physical Examination

Physical examination revealed mild tracheal sensitivity and normal bronchovesicular lung sounds in all fields. Cardiac auscultation revealed a grade 2/6 left systolic murmur and a heart rate of 120 bpm. The dog was mildly overweight (body condition score 6/9), but the remainder of the physical examination was within normal limits.

Laboratory Results

CBC and urinalysis were unremarkable, with the exception of elevated alkaline phosphatase level (991 IU/ml; normal range, 15 to 127 IU/ml) that was probably due to steroid administration.

Ask Yourself ...

Imaging

While the lungs are underinflated in the thoracic radiographs (Figure 1), they reveal a minor difference in the diameter of the caudal lobar bronchi between inspiratory and expiratory radiographs. The pulmonary parenchyma was within normal limits.

FIGURE 1A

Bronchoscopy revealed grade 2/4 cervical and intrathoracic tracheal collapse. Lobar bronchi exhibited varying degrees of collapse, with 95% obstruction of the bronchus to the left cranial lung lobe noted at rest. Dynamic obstruction of the bronchus, with 50% collapse of the airway during respiration (Figure 2), was found in the left caudal lung lobe. Similar changes were noted in the right middle and accessory lung lobes. Mucosal proliferation and edema and epithelial irregularities were noted throughout the airways (Figure 2).

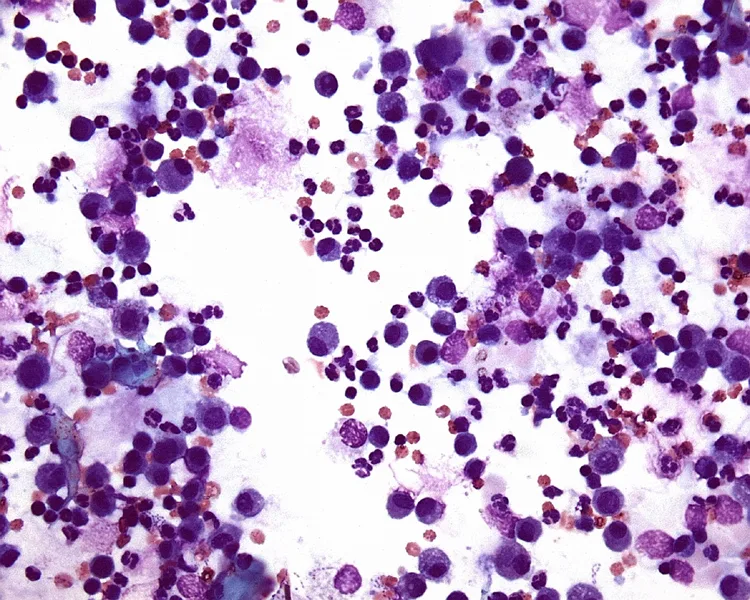

Bronchoalveolar lavage of the left and right caudal lung lobes was performed. Both samples were hypercellular (4400 to 5500 cells/µl; normal range, 200 to 400 cells/µl) and showed evidence of suppurative and granulomatous inflammation as well as previous hemorrhage (neutrophils, 6% to 24%; normal range, 5% to 8%) (Figure 3). Aerobic bacterial culture revealed Bordetella bronchiseptica organisms in pure culture. No Mycoplasma species or anaerobes were isolated.

Bronchoscopic image reveals 50% collapse of the left caudal lobar bronchus, mucosal nodules, and epithelial irregularities.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (original magnification, 100×) reveals neutrophilic inflammation and hemorrhage.

Bordetella infection most commonly results in a self-limiting illness. An acute, seal-bark cough generally develops 2 to 10 days after exposure to an infected animal (often a younger animal from a shelter source). Physical examination is remarkable for dramatic tracheal sensitivity and paroxysmal coughing.

The case described here is interesting for several reasons. First, the cough was chronic and the source of exposure to Bordetella organisms was unknown. The dog may have been infected at the time of anesthesia for the dental procedure or while boarding. Second, the dog had no clinical response to an antibiotic that often displays in vitro efficacy for Bordetella organisms isolated at our hospital. Finally, the history and physical examination were classic for chronic bronchitis with airway collapse, which complicated the dog's presentation.

The number of B. bronchiseptica organisms in the airways can be reduced by nebulization with gentocin, and this dog was treated daily for 5 days with 4 mg/kg of gentocin administered via an ultrasonic nebulizer connected to a facemask. After the dog was treated, coughing was reduced by 80%. The mild, persistent cough could have reflected failure to clear Bordetella organisms from the airways, although it was considered more likely that it was due to chronic airway changes associated with airway collapse and inflammation. Further reduction in cough was achieved with oral administration of extended-release theophylline 10 mg/kg Q 12 H.

Take-Home Messages

Infection with Bordetella bronchiseptica can lead to chronic cough.

Collection of airway samples allows most appropriate therapy.

Airway collapse is difficult to diagnose in the absence of bronchoscopy.

Collapse of large and small airways can complicate therapy of small-breed dogs with cough.

Although Bordetella organisms demonstrate in vitro susceptibility to numerous antibiotics, nebulization with gentocin should be considered to reduce bacterial organisms in the airways of dogs with clinical signs.

TX at a Glance

Gentocin 3 to 5 mg/kg by aerosol administered via an ultrasonic nebulizer connected to a facemask.