Exploratory celiotomy is commonly done for diagnosis and treatment of a variety of medical conditions in dogs and cats. Specific indications may include intraabdominal foreign bodies, masses, abscesses, or granulomas; uncontrolled abdominal hemorrhage; gastrointestinal or urinary tract obstruction; radiographic evidence of pneumoperitoneum; persistent vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain with no detectable cause; findings on cytologic evaluation of abdominal fluid consistent with peritonitis or leakage of urine or bile; estrus in spayed female dogs; or cryptorchidism. Exploratory celiotomy can also be used to obtain biopsies, cytologic evaluation, and cultures for diagnosis of the underlying disease or as a prognostic indicator, as in the case of nonresectable neoplasia.

Types

Complications are observed in 26% to 30% of dogs and cats surviving the procedure.1,2 Most complications result from the underlying disease process; however, they can also be related to the incision (7.5%), anesthesia (5% to 22%), or the procedure itself (17% to 28%).1,2 In one study, complications were highest in patients with gastrointestinal foreign bodies, hepatic lipidosis, ureteral abnormalities, intestinal intussusception, pancreatitis, hepatic neoplasia, and lymphoreticular neoplasia.1 Wound-related complications and infections are higher with surgery duration greater than 90 minutes. Overall mortality rates range from 17% to 27%; euthanasia, done because of the extent of the underlying disease or poor prognosis, is the most common cause of death.1,2

Complications can occur both during and after the procedure. Intraoperative complications may include hemorrhage, inadequate ventilation or perfusion, and inadvertent damage to tissues. Postoperative complications are associated with the abdominal incision (i.e., pain, swelling, seroma formation, infection, dehiscence, or suture reaction), surgical manipulation (i.e., diarrhea, ileus, adhesions, seeding of tumor cells, pancreatitis, hemorrhage); surgical error (i.e., iatrogenic foreign bodies, peritonitis, pneumothorax, sinus tracts from nonabsorbable braided ligatures or nylon cable ties); or primary disease. Some complications, such as hypothermia, pain, and swelling, are so common that clinicians may not consider them to be complications.

Prevention

Blood Analysis

Because severely ill patients are more likely to have complications, preoperative diagnostics and stabilization are critical.

Perform a CBC and analysis of serum biochemistries and electrolytes.

Evaluate urine for evidence of renal insufficiency (i.e., decreased urine specific gravity in the presence of azotemia), infection, hemorrhage, or protein loss.

Perform platelet counts, measurement of buccal mucosa bleeding time, and coagulation profiles in patients with sepsis, liver disease, significant hypoproteinemia, or suspected bleeding tendencies. Low platelet counts confirm thrombocytopenia, whereas prolonged buccal mucosal bleeding time in an animal with a normal platelet count is an indicator of platelet dysfunction or von Willebrand's disease.3

Activated clotting time measures deficiencies of all clotting factors except factor VII and can be used as a screening test for disorders of secondary hemostasis. If activated clotting time is abnormal, prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time should be measured.3

Perform crossmatches in animals that may require transfusions.

Corrective Measures

If possible, correct electrolyte, acid-base, and glucose abnormalities before anesthesia. Animals with coagulopathies usually require perioperative transfusions of fresh frozen plasma or fresh whole blood, and animals with PCV 25% or less are often given packed red cells. Vitamin K therapy (2.2 mg/kg SC followed by 1.1 mg/kg SC Q 12 H) can be initiated in animals with prolonged clotting times secondary to cholestasis or other malabsorptive syndromes; this therapy should correct the coagulopathy within 1 to 2 days.3 In patients with pressure abnormalities or expected fluid loss, place a jugular catheter to measure central venous pressure. Use hetastarch (5 to 40 ml/kg/day IV) for oncotic support in animals with hypoproteinemia; hetastarch can be combined with crystalloids in patients with IV fluid-volume deficits.4

Pain

Many animals that undergo exploratory celiotomy are already in pain, and postsurgical discomfort is to be expected. Preemptive analgesia reduces intraoperative anesthetic requirements and potentially decreases the duration and severity of postoperative pain.5 Options include systemic opioids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, fentanyl patches, local or regional blocks, and CRI of lidocaine or ketamine. A combination of therapies is often given. In addition to analgesic effects, lidocaine may have other positive benefits, such as improving gastrointestinal motility, decreasing neutrophil chemotaxis and platelet aggregation, and protecting cells through weak inhibition of calcium channels. A CRI of lidocaine (10 to 25 µg/kg/minute in cats or 25 to 50 µg/kg/minute in dogs) can be delivered by syringe pump or diluted in crystalloid fluids. Use lidocaine CRI with caution in cats since they are susceptible to dose-related neurotoxicity or decreased cardiac function.

Anesthetic Monitoring & Antibiotics

Monitor ECG, blood pressure, SPO2, and end-tidal CO2 once the animal is anesthetized. Mechanically ventilate patients with conditions that may cause respiratory compromise, such as diaphragmatic hernia, ascites, or gastric distention. Animals with hypotension (systolic BP < 90 mm Hg, mean BP < 60 mm Hg) that do not respond to IV fluids or reduction in anesthetic delivery may require positive inotropic support (i.e., IV dopamine CRI 4 to 6 µg/kg/minute).6

Give broad-spectrum antibiotics intravenously at induction if contamination is expected, although administration can be delayed until intraoperative cultures are obtained. In animals without infection, severe contamination, or tissue necrosis, discontinue antibiotics within 6 hours after the procedure.

Preoperative Preparation

Preoperative preparation should be thorough but efficient, since duration of anesthesia correlates with infection rates. If possible, clip the patient immediately before surgery to prevent bacterial colonization of microscopic nicks from clippers. In the surgical suite, place the animal on or under a forced-air warming system to reduce heat loss, and perform a final preparation of the surgical site.

Surgical Procedure

If possible, make the incision directly on the linea alba, particularly if the patient has a bleeding tendency. Incisions can be extended cranially to the xyphoid; however, pneumothorax may occur if it is extended too far or if the cranial portion of the incision tears from excessive retraction.

To reduce bacterial translocation and hypothermia, moisten the laparotomy pads placed along the incision only on the surfaces that contact the intraabdominal tissues, especially if cloth drapes are used.

Perform a thorough, systematic exploration before undertaking definitive therapy.

Surgical technique should be guided by Halstead's basic principles: maintenance of asepsis, gentle handling of tissue, accurate hemostasis, closure of dead space, accurate tissue apposition, and avoidance of tension or vascular compromise.

Do the cleanest procedures first-for example, perform liver biopsy before enterotomy.

Isolate organs with moistened laparotomy pads to contain spillage and reduce generalized contamination.

If no primary lesion is found or the primary disease cannot be resolved, sample organs and fluids for cytologic evaluation, biopsy, or culture.

Consider feeding tubes for patients that are malnourished, anorexic, or vomiting.

Once a contaminated organ or structure has been closed or removed, change gloves and instruments. Continuous suction drains can be placed in local areas of infection, or in multiple sites throughout the abdomen if peritonitis is present. Before closure, flush the abdominal cavity with warm sterile saline and suction it dry to remove contaminants.

Postsurgical Measures

After surgery, measure PCV, total protein, and blood glucose to provide a baseline for future comparison. Administer analgesics on a scheduled basis for the first 12 to 24 hours and then on an as-needed basis. Many animals require continued fluid administration and monitoring of vital signs.

Specific Complications: Prevention & Treatment

Hernia

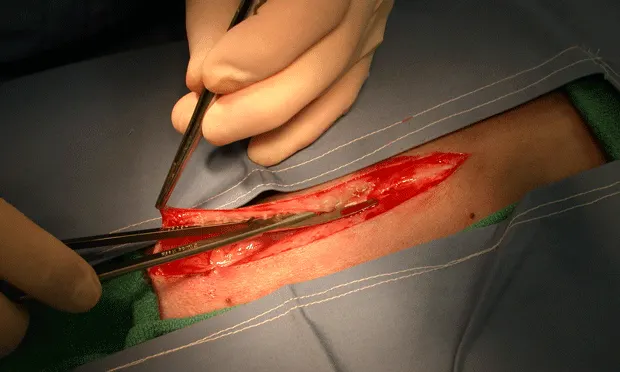

Incisional hernias are most likely to occur from poor surgical technique-that is, suture bites that are too small or that do not contain the external rectus sheath. In dogs, the subcutaneous fat adheres to the linea, obscuring visualization of the site at the time of abdominal incision and closure. This fat can be cleared immediately after subcutaneous incision with a push-cut motion (Figure 1. The fat attachments to the linea are transected with a push–cut motion to reduce dissection and expose the external rectus sheath). using Metzenbaum scissors. Dissecting the subcutaneous fat away from the linea makes the white external rectus sheath visible (Figure 2. The right external rectus sheath is exposed. The remaining fat attachments above the left external rectus sheath should also be transected) so that it can be incorporated within each suture bite (Figure 3). If the fat has not been excised from the linea, it can be elevated at the time of closure.

The fat attachments to the linea are transected with a push–cut motion to reduce dissection and expose the external rectus sheath.

The right external rectus sheath is exposed. The remaining fat attachments above the left external rectus sheath should also be transected.

In this dog, the subcutaneous fat attachments were not transected during the abdominal approach. The subcutaneous fat is being retracted with thumb forceps to expose the edge of the rectus sheath, which has been incorporated in the tissue bite on the needle.

Closure of the peritoneum and internal rectus fascia is not necessary in dogs and cats, since the external rectus sheath provides the greatest strength to the wound. Simple continuous closure is faster and causes less tissue reaction than and is as strong as interrupted closure.

On rare occasions, incisional hernias occur because the animal's rectus abdominus fascia is weak. In these cases, the rectus fascia actually tears longitudinally along the sites of suture penetration. Affected animals may require wider and thicker tissue bites within each suture or support with synthetic materials (i.e., porcine small intestinal submucosa sheets) to prevent reherniation. Interrupted suture patterns are favored in hernia repair.

Suture failure of abdominal wall closures is uncommon; however, the security of simple continuous patterns relies only on 2 to 3 knots at each end of the incision. Polypropylene, polydiaxanone, and polyglyconate have memory and tend to half-hitch when tied. When tying knots, particularly to the loop end of the suture (at the completion of closure), place the short end of the suture under greater tension and make sure each throw of the knot drops straight down over the incision line to square the throw. The suture ends of a square throw lie flat against the abdominal wall, whereas the short end of a half-hitched throw stands straight up after the throw is completed.

Swelling of the Incision and Cellulitus

Incisional swelling is relatively common after celiotomy in cats; suggested causes include surgical trauma, seroma formation, suture reaction, use of subcutaneous closure, and infection.7 Aseptic technique and surgical duration less than 1 hour decrease the risk for postoperative wound infections. In most animals, incisional infection involves only the superficial layers. Administration of a systemic, broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, plus local wound care (i.e., hot-packing) and prevention of self-trauma (i.e., use of an Elizabethan collar), usually resolve the problem.

If infection persists, remove any skin and subcutaneous sutures and collect a biopsy of deep wound tissues for histologic and cytologic evaluation and culture. Manage the wound open, with daily bandage changes and topical cleansing, or perform debridement and close the wound after drain placement.

Sterile suture reactions are rare but can occur; the author has noted such reactions most often when polydioxanone is used in the linea. Suture sinuses have also been reported in dogs that have undergone closure of the linea with monofilament, nonabsorbable suture material.8 Large, thick knots may cause irritation to overlying tissues, and continued presence of foreign matter delays clearance of secondary infection. Animals presented with severe thickening and fistulas from suture reactions may require en bloc resection of affected tissue and closure with a less reactive material.

Incisional swelling secondary to seeding of tumor cells was reported in six dogs 2 to 30 weeks after abdominal surgery.9 Histologically aggressive, exfoliative carcinomas, such as transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary tract, are more likely to seed the primary incision site. Since occurrence of tumor seeding correlates with the number of contaminating cells, reduction of contamination (i.e., use of laparotomy pads to isolate the organs undergoing biopsy and changing gloves and instruments) is critical for prevention.

Ileus

Ileus is a common complication of abdominal surgery. It may also be caused by focal or generalized peritonitis, prolonged intestinal distention, enteritis, drugs (i.e., opioid agonists), electrolyte or fluid imbalances, or intestinal obstruction or ischemia.10-12 Animals are usually affected within the first 24 hours after surgery and may have gaseous or fluid abdominal distention, pain, or vomiting.

Adynamic (functional) ileus must be differentiated from obstructive ileus, which may require further surgical intervention. Intestinal wall thickness, lumen diameter, and peristalsis can be detected on ultrasonography; however, the presence of residual intraabdominal air after surgery may interfere with this imaging technique. Plain or contrast radiography is often used to diagnose functional ileus.

Animals with adynamic ileus should be rehydrated and administered appropriate analgesics. Any primary cause (such as peritonititis or electrolyte deficiencies) should be treated. Dogs with decreased serum magnesium (<1.2 mg/dl) can have severe ileus and vomiting that resolves with IV magnesium supplementation (30 mg/kg IV over 2 to 24 hours). Patients with intestinal edema may respond to hetastarch administration.

For animals with no apparent underlying cause, prokinetic agents, such as cisapride, metaclopramide CRI (1 to 2 mg/kg/day), lidocaine CRI (25 µg/kg minute), or erythromycin, can be used to stimulate intestinal motility. Enteral nutrition should be encouraged; dogs and cats that are not vomiting can be fed after surgery on the same day, even if gastric or intestinal procedures have been performed. Animals that do not respond to therapy should be reevaluated for obstructive gastrointestinal disease or other metabolic problems.

Peritonitis

Types

Postoperative peritonitis most commonly occurs from leakage at gastrointestinal surgery sites.11,12 It may also result from reaction to foreign bodies, such as retained surgical sponges or contaminated nonabsorbable suture or implants. Mild inflammation of the intestines is expected if visceral surfaces become dry during celiotomy.

Prevention

Prevention of peritonitis focuses on appropriate surgical technique-isolating viscera, keeping them moist, performing wide resections of diseased tissue, maintaining blood supply, avoiding tension, using drains if needed, and counting sponges and laparotomy pads before opening and closing the abdomen. During intestinal resection and anastomosis, everted mucosa conceals the submucosa, resulting in suture bites that miss this critical holding layer, particularly along the mesenteric surface. Resection of the everted mucosa, or use of a modified Gambee pattern, improves visualization during suturing. Intestinal anastomoses can be done with simple continuous patterns without increasing risk for dehiscence. Omentalization of gastrointestinal surgery sites or drained abscesses improves local blood supply and thus speeds healing.

Dehiscence

Dehiscence occurs in 7% to 16% of patients undergoing small intestinal surgery and is associated with a mortality rate of over 70%.11 Dehiscence of the small intestine is more common in dogs that undergo surgery for traumatic lesions or foreign body obstruction. Clinical signs usually occur 3 to 5 days after the procedure, when integrity of the enteric closure is primarily dependent on the suture. Early clinical signs can be nonspecific (i.e., vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, or abdominal pain), but can progress to signs of shock.

Diagnosis

Dogs with septic peritonitis have increased band neutrophils on CBC.12 Other blood value changes are nonspecific but help guide treatment of the patient. Plain abdominal radiographs and ultrasonography are difficult to interpret after gastrointestinal surgery because of air and fluid introduced during celiotomy.

Abdominal fluid analysis is the most useful test for diagnosing generalized peritonitis. Fluid can be obtained by blind or ultrasonography-guided abdominocentesis or by diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Abdominal fluid cell counts are increased in dogs that have undergone uncomplicated intestinal surgery; however, the presence of degenerate or toxic neutrophils, bacteria, or plant matter is indicative of peritonitis.12

Dogs and cats with septic peritonitis have a blood-to-peritoneal glucose concentration difference greater than 20 mg/dl. In addition, in dogs with septic peritoneal effusion, the blood-to-peritoneal fluid lactate concentration difference is less than -2.0 mmol/L.14 Abdominal fluid should be submitted for culture and sensitivity and Gram stain to help guide antibiotic selection, since administration of inappropriate antibiotics is associated with a poorer prognosis.

Timing

Onset of clinical signs in animals with retained surgical sponges can be delayed if there is no bacterial contamination. In these animals, the presence of a mass may be the only abnormality (Figure 4), and diagnosis can be delayed for months to years after surgery. On radiographs, the encapsulated sponge may appear as a localized gas lucency with a speckled or a whirl-like pattern. On ultrasonography, the mass is hypoechoic with an irregular hyperechoic center.13

Sponge foreign body. This female dog presented with hematuria and constipation more than 1 year after ovariohysterectomy. The sponge granuloma had eroded through the bladder and was compressing the colon. Resection of bladder wall, colonic serosa, and uterine body were required to remove the mass.

Treatment

Dogs with peritonitis should be treated with crystalloids, colloids, oxygen, analgesics, and broad-spectrum antibiotics (i.e., ampicillin with a third-generation cephalosporin or an aminoglycoside). Give fresh frozen plasma if clotting times are prolonged. Perform surgery as soon as possible to correct the underlying problem and to lavage and suction out any contamination.

In patients with extensive contamination or fibrin deposition, place three to five closed-suction drains (Figures 5 and 6) before closing the abdominal cavity. These drains should exit out separate incision sites through the lateral body wall and be secured with purse-string and finger-trap sutures. Postoperative bandaging is easier in male dogs if the drains exit cranially.

Multifenestrated closed-suction drainage system. The suction bulb has a one-way valve that prevents backflow of fluid into the drain.

Multiple continuous suction drains in a dog with peritonitis from gastrointestinal perforation

The drains will remove large quantities of fluid, including normal peritoneal fluid, so the duration of drain retention depends on the character of the fluid. Remove the drains once the fluid becomes clearer and toxic cells are not seen on a fresh sample (usually in 2 to 3 days).

While the drains are in place, the animal will lose fluid, electrolytes, protein, and red blood cells; therefore, intensive care and monitoring are required. Determine the volume of fluid administration by calculating maintenance requirements plus the amount of fluid lost from the drains. Most animals require continued oncotic support while the drains are in place. Continue broad-spectrum antibiotics until culture results return.