Feline Heartworm Infection

Profile

Definition

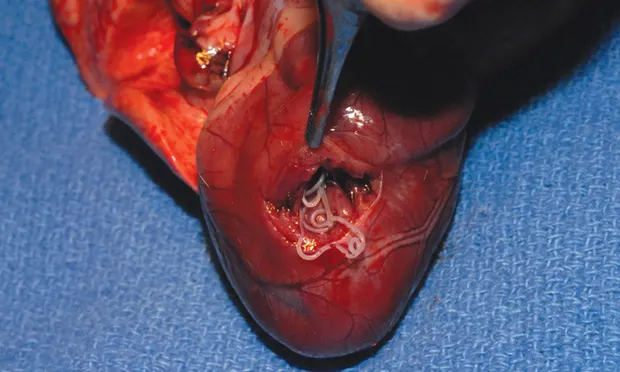

Disease of the pulmonary vasculature and pulmonary parenchyma of cats caused by Dirofilaria immitis (Figure 1, above)

Figure 1. A single female heartworm in right ventricle of a cat. No other worms or fragments found. Diffuse lung disease was demonstrated. Photo courtesy of Dr. Ray Dillon

Related Article: Diagnostic Challenges of Feline Heartworm Disease

Geographic Distribution

Infection in cats is found in all 50 states, with greater prevalence in warmer climates.

Prevalence

Because cats are not the natural host of D immitis and clearance of third-stage through fifth-stage infective larvae (ie, L3-L5, immature) can occur, prevalence of feline heartworm infection in endemic areas is ~10% that of infection in dogs1,2 (see Heartworm Infection: Cats vs Dogs).

Approximately 25% of feline heartworm cases occur in purely indoor cats.3

Transmission

Mosquitoes extract the L1 microfilarial stage of D immitis from an infected dog, cat (unlikely), or other host.

L1-L3 molting occurs within the mosquito.

Once D immitis reaches L3, the host mosquito can transfer it into a cat’s bloodstream via a bite.

L3-L5 (adult) molting may occur, although larvae often fail to mature.

Related Article: Feline Heartworm Infection

Risk Factors

Any cat not receiving prevention is at risk for heartworm infection.

Risk for infection is higher in endemic areas.

Pathophysiology

Stage 1

Inflammation caused by presence of immature worms

Occlusive hypertrophy of small pulmonary arterioles occurs within 3–4 months of infection.

Pulmonary inflammatory response is called heartworm-associated respiratory disease (HARD); signs appear similar to asthma.

Substantial lesions are noted in arterioles, arteries, alveoli, and bronchioles.

Heartworm infection can be arrested at this stage, but histologic changes (Figure 2) and clinical signs may persist.

Live heartworms can suppress immune function, allowing cats to better tolerate infection.

Figure 2. Histopathology of the pulmonary artery of a cat infected with D immitis. Courtesy of Dr. Julia A. Conway

Stage 2

Mature worms die and degenerate.

The process incites more pulmonary inflammation.

Thromboembolism, fatal acute lung injury, and anaphylaxis can occur.

Adult infection is usually limited to <5 worms.

Signs & Examination

Cats are often subclinical

Coughing and/or dyspnea are the most common signs.

Up to 50% of affected cats present with respiratory distress or tachypnea.

Increased bronchovesicular sounds may be auscultated in the thorax.

Vomiting, neurologic signs, and sudden death can occur.

Caval syndrome is uncommon (because of small number of worms present).

Heart murmurs are unusual and suggest primary cardiac disease.

Diagnosis

Laboratory Findings

Serum biochemistry profile results are often within reference ranges.

CBC may show eosinophilia.

Imaging

Radiography

Cardiac changes consistent with heartworm disease are seen in ~50% of cats with positive result for heartworm infection.

Pulmonary artery blunting and tortuosity is less common in cats than in dogs.

If artery blunting is present, the right caudal lobar artery will be affected first.

Right ventricular and mainstem pulmonary artery enlargement are uncommon.

The most common abnormality is diffuse bronchial or broncho-interstitial pattern consistent with feline allergic airway disease.

Echocardiography

May confirm if serologic testing is suggestive of heartworm disease

Helps rule out primary or concomitant heart disease

Although fewer worms are present in feline hearts (as compared with dogs), worm size relative to the small heart can make worms easier to detect.

Worms may be visualized, but quantification is difficult.

Other Diagnostics

Antibody testing detects antibodies to larvae and adult worms.

Sensitive but not specific for presence of adult worms

Negative result indicates that heartworm infection is unlikely.

Significant incidence of false-positive results (eg, 76.1%–77.2% specificity)4

False-positive results may reflect previously resolved infection, larvae that did not/will not develop to adults, and aberrant adult infection.

Antigen testing detects mature female worms.

More specific (98.1%–99.4%)5 than antibody testing but not as sensitive

Positive result indicates heartworm infection, but false-negative result can occur with immature or male-only infections.

These infections are common (small number of worms).

Combination antigen–antibody testing is recommended.

Tests to detect microfilariae are typically not performed, as microfilaremia (ie, presence of heartworm offspring) is rare and transient in cats.

Treatment

Adulticide Therapy

No approved adulticide therapy is available for cats because of high mortality from pulmonary thromboembolism and possible anaphylactic-like reaction to dead or dying worms.

Therapy is palliative only.

Emergency Therapy for Signs

Oxygen therapy

Bronchodilators

Fast-acting corticosteroids (eg, dexamethasone)

Supportive care (eg, fluid therapy)

Chronic Therapy

Oral or inhaled corticosteroids

Oral or inhaled bronchodilators

Doxycycline

Adjunct Therapies

Antiemetics

Doxycycline to eliminate Wolbachia pipientis (symbiotic bacteria harbored by D immitis)5,6

Weakens adult worms and their fertility

May improve pulmonary pathology

Macrocyclic lactones may decrease life span of adult worms.

Ultrasound-guided manual worm removal

Medications

Dexamethasone

For emergency treatment at 1 mg/kg IV

Doxycycline

10 mg/kg q12h PO for 3 weeks starting at diagnosis

Macrocyclic lactones

Preventive medication should begin at diagnosis and continue for life.

Prednisolone

Often used to decrease pulmonary inflammation

2 mg/kg PO q24h, then tapered to lowest effective dose

Bronchodilators

Aminophylline at 4 mg/kg PO q24h

Terbutaline 1.25 mg/cat PO q12h

In General

Relative Cost

Treatment cost is relatively low ($–$$), as no adulticide therapy is available and care is supportive only.

Respiratory distress secondary to heartworm infection can be an emergency and increase cost.

Prognosis

Prognosis is guarded.

Infection can be fatal, as no acceptable treatment is available; however, infection can be cleared naturally.

Prevention

Heartworm disease is preventable with administration of macrocyclic lactones (see Heartworm Preventive Options for Cats).

Prevention should be started at 8 weeks of age and continue for life.

Medications should also include efficacy against some internal and external parasites.

AMARA ESTRADA, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology), is an associate professor and associate chair for in the department of small animal clinical sciences, University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine. Dr. Estrada’s interests include electrophysiology, pacing therapy, complex arrhythmias, cardiac interventional therapy, and cardiac stem-cell therapy. She has contributed to numerous research and clinical publications on emergency and critical care medicine and is associate editor of Journal of Veterinary Cardiology. Dr. Estrada earned her DVM from University of Florida before completing an internship at University of Tennessee and a residency in cardiology at Cornell University.

WENDY MANDESE, DVM, worked in general practice for 11 years in Orlando and Gainesville. Currently, she is a clinical assistant professor in the department of primary care and dentistry at University of Florida, where she also earned her DVM.