The Case: Misdiagnosed Vomiting

HistoryFirst Presentation

An 11-year-old Golden retriever was referred for 10 days’ vomiting and lethargy; water intake normal

Two prior episodes of foreign body obstruction requiring surgery

Abdominal radiographs: hemoclips from previous surgeries within abdomen with small amount of gas in normal-sized small intestines/linear metallic object in mid abdomen

Thoracic radiographs: normal

U/S: multiple well-defined hypoechoic nodules in liver and spleen/intestinal gas without evidence of gastrointestinal obstruction

Canine pancreas specific lipase (spec-CPL) assay: normal

Vomiting resolved over 12 hours after admission for observation/fluid therapy/antibiotics (ampicillin)/antiemetics (dolasetron and maropitant)

Conclusion: metallic object not obstructive due to lack of evidence on radiographs and ultrasound/”occult” pancreatitis strongly considered

Discharged with bland diet and antibiotics

Second Presentation

Re-presented with anorexia/lethargy 5 days later; no vomiting

Prominent prescapular lymph nodes; persistent fever (103.3⁰ F)

CBC/serum biochemical profile/lymph node cytology performed

Discharged with injectable maropitant while awaiting results

Diagnostic Results

Suspicious for lymphoma although reactive lymphoid hyperplasia could not be ruled out

Nucleated cell population of 50% to 70% lymphocytes with condensed chromatin/30% to 50% intermediate-to-large blasts with slightly basophilic cytoplasm, finely stippled chromatin, often prominent large nuclei

Few large lymphoblasts; occasional plasma cells

PCR assay negative for lymphocyte clonality

Third Presentation

Presented again due to lack of clinical improvement 8 days after initial presentation

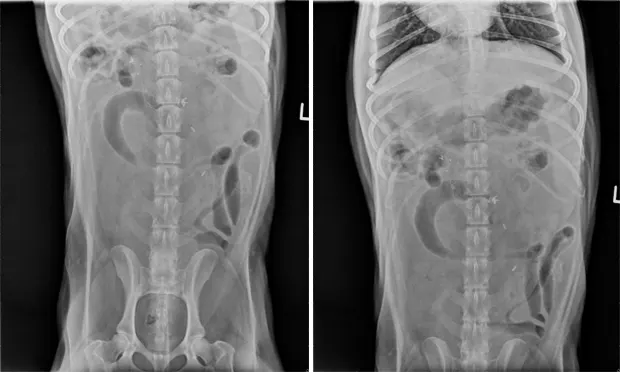

Abdominal radiographs: corrugated-appearing proximal duodenum/irregular gas bubbles/previously noted metallic foreign material in same position ( See the abdominal radiographs )

U/S: multiple corrugated mid and cranial loops of distended small intestine/hyperechoic line in central lumen (suggesting linear foreign body)/surrounding mesentery hyperechoic (suggesting focal peritonitis)

Normal empty caudal small intestinal loops (suggesting segmental mechanical ileus due to foreign body obstruction)

Emergency exploratory surgery: linear foreign body from pylorus through stomach body to proximal jejunum/76 cm red, edematous, nonviable bowel (pylorus, duodenum, jejunum)/3 perforations on mesenteric border

Treatment

Side-to-side gastrojejunostomy with GIA stapler

Required removal of right pancreas limb with cholecystojejunostomy to allow bile flow into intestines

Procedure took 4 hr general anesthesia/3.5 hr surgery

Recovery

Pain, hypotension, anemia, hypoalbuminemia with reduced colloid oncotic pressure (12–14 mm Hg, range 21.7–25.5 mm Hg)

Histology of resected tissues: suppurative enteritis/multifocal perforation and fibrinous peritonitis; peritoneal culture yielded Enterococcus bacteria

Realimentation impaired by profound, persistent GI stasis

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Postoperative Treatment

Colloids/crystalloids/dopamine/ephedrine for hypotension

Combination antibiotic therapy with ceftazidime and metronidazole

Fentanyl/lidocaine/ketamine for pain

Packed red blood cells for anemia

Hetastarch 6%/human albumin (25 g)/canine plasma transfusions for hypoalbuminemia/reduced colloid oncotic pressure

Metoclopramide/dolasetron/maropitant/erythromycin for massive gastric/gastroesophageal reflux

Nasogastric tube for intermittent decompression

Frequent monitoring for dehiscence of intestinal anastomosis by abdominocentesis/cytology

Outcome

10 days after surgery, septic neutrophilic inflammation was detected in the abdominal fluid

Owner opted for euthanasia due to grave prognosis

The Specialist's OpinionThis dog should have received repeat abdominal imaging at the second presentation to evaluate the previously documented foreign material, which may have revealed the linear foreign body before the process advanced too far. During the dog’s first visit, clinical improvement made additional imaging an elective test (albeit a desirable one). In the follow-up visit, repeat imaging would have been wise when it was realized that clinical improvement was not sustained. However, lack of renewed vomiting created a false perception that obstruction was unlikely.

The Road Not Taken…Dogs are commonly encountered in veterinary practice with nonobstructive intestinal foreign material passing in the feces. In this case, intestinal obstruction was properly considered, but improvements in the dog’s clinical condition following fluid therapy were overinterpreted. The lack of vomiting and renewed appetite created a false picture of health. In hindsight, these clinical improvements could be attributed to rehydration and other supportive care measures including antiemetic treatment. The antiemetic agents currently available are extremely effective and may mask continued underlying disease. Repeating the plain radiographs within 24 to 72 hours of presentation might well have led to the proper diagnosis and treatment.

Radiographic obstruction was not present on the day of presentation, but so-called “high” gastrointestinal obstructions are difficult to recognize compared with mid-to-lower intestinal obstructions. In this case, the difficulty in making a diagnosis radiographically was compounded by overreliance on ultrasound. It is easy to say in hindsight that the outcome of this case would have been improved had an exploratory celiotomy been performed before intestinal perforation occurred.

Pancreatitis, Nonspecific Gastroenteritis, LymphomaBecause the imminent intestinal obstruction was not recognized, the attending veterinarians properly considered alternative diagnoses such as pancreatitis and nonspecific gastroenteritis. Nonspecific gastroenteritis was suspected based on improvements following symptomatic therapy, but “occult” pancreatitis was strongly considered, which can be difficult to rule in or rule out given currently available diagnostic tests. This dilemma is often faced when clinicians are confronted with a vomiting patient. Recent literature indicates that elevated serum amylase and lipase values are neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis of pancreatitis. Instead, a diagnosis of pancreatitis is frequently based on abdominal ultrasound findings and/or assays for canine pancreas specific lipase (spec-CPL). Although these diagnostic tests are more reliable, they are not infallible.

Lastly, the attending veterinarians may have been distracted by a lymph node cytology report indicating possible lymphoma. Lymphoma is a tenable consideration in an 11-year-old dog. Molecular diagnostics and flow cytometry are now commonly used in the workup of canine lymphoma. The sensitivity of PARR, a PCR assay for lymphocyte clonality, for canine lymphoma is approximately 90%.There is a 10% chance of a false negative result. The consideration of lymphoma in this case may have diverted attention from the actual problem at a critical time.

David Senior, BVSc, DACVIM, DECVIM-CA, graduated from University of Melbourne in 1969 and spent the following year in a rotating clinical internship there. He then worked in a predominantly dairy/beef practice in Alberta Canada for 4 ½ years before completing a residency in small animal internal medicine at University of Pennsylvania. After many years on faculty at University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine, where he specialized in diseases of the urinary tract, in 1992 he became professor and head of the Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences at Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine. In 2007 he was named associate dean of Advancement and Strategic Initiatives. Dr. Senior is the Conference Coordinator of the NAVC and a member of the Advisory Board of Clinician’s Brief.

The Generalist's OpinionIn the radiographs presented, there is a metallic foreign body noted on the initial radiographic views. This was dismissed as incidental due to lack of other evidence of obstructive disease. The dog in this case, however, had experienced two previous episodes of obstruction requiring surgical correction. Any previous surgery involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract puts a patient at risk for future obstructive episodes due to adhesion formation. Loops of bowel can form sharp bends that impede passage of material.

It’s important to remember that there are few tests that are 100% diagnostic regardless of the degree of technological advancement of the modality. A recent article discussed the limitations of advanced imaging techniques in human medicine and a concerning trend toward an over-reliance on test results as opposed to clinical examination findings. 1 The case of this golden retriever illustrates a similar point: although radiographic and ultrasound findings did not reveal an obvious obstruction, the history and clinical signs were highly suggestive of the problem. In addition, the imaging did reveal foreign material in the GI tract and a very mildly dilated loop of bowel, which were not reevaluated with additional imaging, neither at the initial presentation nor when the dog was re-presented 5 days later. The initial spec-CPL was normal and there was no sign of pancreatitis on ultrasound. The enlarged prescapular lymph nodes were a potential issue, but GI-related lymphoma involves intestinal wall thickening, which should be evident on ultrasound. Given all of this, there was no definitive diagnosis that explained this dog’s signs. Additional imaging would have helped shed light on the situation.

The fact that it took 5 days to recheck this dog was also unfortunate. Ideally clients receive a phone call to check on their sick pet’s progress a day or two after being seen. Most veterinary software programs have a built-in call-back feature. A patient can be flagged during an initial exam and either the veterinarian or a technician can follow up with a call. This practice facilitates good medicine and also reflects positively on the practice in general.

This was a case with some unfortunately confounding test results that led to a significant delay in treatment. During the recheck examination in any case in which the clinical signs have not improved, the veterinarian should “rethink” whether or not the initial diagnosis was correct. Part of this evaluation should give consideration to the accuracy of the testing modality, including operator experience in tests such as ultrasound. There will always be cases and diagnoses that slip through the cracks. An entire rethinking of cases at any recheck will help minimize these occurrences.

1. That Middle-of-the-Night Bellyache: Appendicitis? Klass P. NY Times, Aug 9, 2010. Barak Benaryeh, DVM, DABVP, is the owner of Spicewood Springs Animal Hospital. He graduated from University of California-Davis School of Veterinary Medicine in 1997 and completed an internship in Small Animal Medicine, Surgery, and Emergency at University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Benaryeh has also taught practical coursework to first-year veterinary students and was a primary veterinary surgeon for the Helping Hands Program, which trains assistance monkeys for quadriplegic people. Dr. Benaryeh is certified by the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners in Canine and Feline Practice.