Canine Multicentric Lymphoma

Sue Ettinger, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology), Tarrytown, New York

Digital calipers can be used to precisely measure lymph nodes. Figures courtesy of Sue Ettinger, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology)

Lymphoma is a collection of cancers arising from the malignant transformation of lymphocytes. The common origin is lymphoreticular cells, even though lymphoma clinically is a diverse group of neoplasms. Lymphoma is one of the most common canine cancers, accounting for 7% to 24% of all canine tumors and 85% of hematopoietic tumors.1

The cause of lymphoma is largely unknown and multifactorial. Genetics can play a role, and chromosomal aberrations have been found.1 Dogs with previous immune-mediated thrombocytopenia have been associated with increased risk.2 Whether immunosuppressive medications can increase risk to dogs is unclear. Environmental causes have also been documented.1

Dogs of any age, gender, and breed can be affected with lymphoma, although affected dogs are typically middle-aged to older.1

Genetic predispositions have been noted in pedigrees of bull mastiffs, otter hounds, rottweilers, and Scottish terriers, pointing to a heritable risk.1 Several breeds, including golden retrievers, boxers, basset hounds, Saint Bernards, Scottish terriers, Airedales, Labrador retrievers, bulldogs, and poodles, are reported to be at increased risk.1,3,4

History

In the early phases, most dogs appear healthy and do not show clinical signs. With cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin (vincristine), and prednisone (CHOP) multiagent chemotherapy protocols, median survival times are 10 to 12 months, and 25% of dogs are long-term survivors (ie, more than 2 years).1

The most common presenting complaint is generalized peripheral lymphadenomegaly. Clients commonly report a rapid increase in lymph node size over a few days to 1 to 3 weeks. When present, clinical signs tend to be nonspecific and include vomiting, diarrhea, melena, anorexia, fever, polyuria, polydipsia, and weight loss.

Physical Examination Findings

The most common physical examination finding is generalized peripheral lymphadenomegaly,3 with multicentric lymphoma involving the peripheral lymph nodes seen in approximately 80% of patients.1,4 (See Figure 1.) A lack of generalized lymphadenomegaly does not eliminate the possibility of lymphoma because some dogs will only have internal (ie, hepatosplenic, GI) involvement. In some lymphoma cases, physical examination findings may be normal and suspicion is raised only when hypercalcemia is identified (eg, during diagnostic evaluation).

Diagnosis

Diagnostic tests can provide prognostic factors and a baseline for future assessment of a patient’s treatment response, and can also help determine if a large tumor burden and risk for acute tumor lysis syndrome with induction of chemotherapy exist. Although performing all tests listed is ideal, veterinarians must converse with clients on a case-by-case basis to help them make informed decisions about how best to proceed.

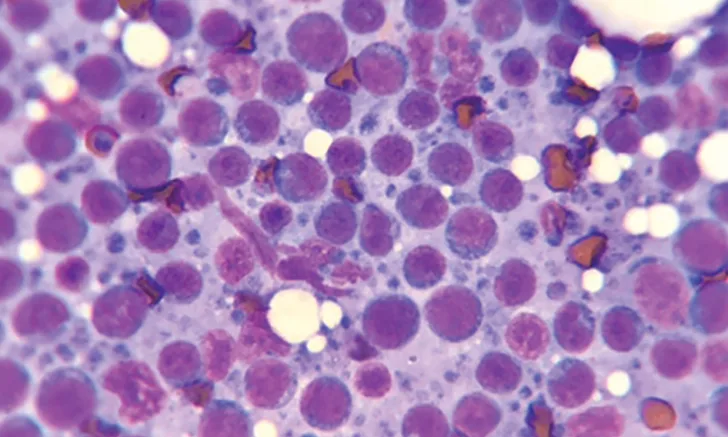

Cytology of lymph node aspirate showing malignant lymphoblasts

Fine-Needle Aspiration & Lymph Node Cytology

After finding lymphadenopathy, confirming lymphoma starts with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and cytologic evaluation of an affected lymph node or organ. (See Figure 2.) Cytology is minimally invasive, less expensive than biopsy, and typically provides rapid results (ie, 1-2 days). Slides can be examined immediately in-house and then sent to a laboratory for confirmation by a pathologist.

In the author’s opinion, aspirating the popliteal lymph nodes, which are easily accessible, is best. Lymph node aspirates rarely require sedation. Avoid the mandibular lymph nodes because they drain the oral cavity and may be reactive.

Canine lymphoma usually is easily diagnosed via FNA cytology as large cell (ie, lymphoblastic) lymphoma. When cytology is inconclusive, histopathology is helpful in identifying and classifying indolent—usually intermediate to small cell—lymphoma. The whole lymph node should be excised and submitted for histopathology.

Phenotyping

Immunophenotyping identifies the cell line of origin (ie, B cell or T cell) and can be accomplished via flow cytometry (FCM) on lymph node aspirates or on a blood sample if there is lymphocytosis.5 If a lymph node biopsy was obtained, phenotype can also be determined via immunohistochemistry on tissue samples.

Phenotype is a strong prognostic predictor for lymphoma.1 FCM can also be useful in determining whether lymphocytes are homogeneous (ie, more consistent with lymphoproliferative disease) or heterogeneous (ie, more consistent with a reactive process).5 When cytology or histology results are ambiguous, additional testing (eg, PCR for antigen receptor rearrangement [PARR]) is available.

Complete Lymphoma Staging

Diagnostics include:

Lymph node cytologic confirmation

CBC

Serum chemistry profile

Urinalysis

Phenotyping

Abdominal ultrasonography

Lymph node histology

Thoracic radiography

Bone marrow cytology

Staging & Prognosis

A complete lymphoma staging (see Complete Lymphoma Staging) should be performed and the results used to assign a WHO clinical stage. (See Table 1.)

Table 1: WHO Clinical Stages of Lymphoma

Because of budget and/or time constraints, not all clients can pursue all diagnostics, so the client should be educated on the options available, and diagnostics should be selected on a case-by-case basis. When selecting tests, the 2 prognostic factors most consistently identified are phenotype and substage (ie, clinically healthy or sick).1 T-cell phenotype is associated with shorter survival time.1

Therapy

Chemotherapy is considered the mainstay. The overall chemotherapy toxicity rate is low, and in the author’s experience, only 15% to 20% of patients experience side effects. Patients are typically treated as outpatients. (See Figure 3.) The primary goal of chemotherapy is to provide the best quality of life possible for as long as possible.

Most patients tolerate chemotherapy administration very well.

Multiagent CHOP protocols, which vary in doses, scheduling, and dose intensity, are frequently recommended.

The University of Wisconsin–Madison protocol is often recommended for clients choosing a combination protocol because it has high complete remission rates and remission duration and is generally well tolerated.1 Clients typically feel treatment was worthwhile and that the dog’s quality of life not only improved from treatment but also was good during treatment.1

Alternatives to CHOP protocols (eg, single-agent doxorubicin, single-agent oral lomustine, the COP protocol) are available, but they generally have lower response rates and shorter remission durations.1

In April, the FDA conditionally approved Tanovea-CA1 (rabacfosadine), a new chemotherapeutic agent to treat lymphoma in dogs that has, to date, demonstrated reasonable efficacy and complete and acceptable safety.6 The overall response rate in clinical studies was 77%.6 A more recent study examined its use in combination with doxorubicin and found an overall response rate of 84%.7

Tanovea can be used as a first-line therapy and in dogs that have failed or relapsed with prior treatment. The chemotherapeutic should be administered under the supervision of a veterinarian experienced in the use of cancer therapeutics, and standard measures for the safe handling of cytotoxic drugs should be used.

Consultation with or referral to an oncologist is recommended for all lymphoma cases because these specialists are knowledgeable about the newest treatments and prognostic data and can help clients explore all options and choose the best treatment for their specific pet and situation.

Lymphoma: Key Points for Clients1,3,4

Lymphoma is a common canine cancer of one of the white blood cells that requires chemotherapy in almost all cases.

Although lymphoma is not curable, it is one of the most successfully treated cancers and the majority (ie, ≈ 80%) of dogs achieve a complete remission with chemotherapy. Higher remission rates are typical with CHOP multiagent chemotherapy protocols. Early detection and treatment are vital for successful outcomes. Accurate diagnostics

can help determine prognosis and assist the client in choosing treatment options.

A variety of protocol options have various potential side effects and response rates. Consultation with a board-certified oncologist is recommended to help understand and navigate the testing and treatment options.

Dogs treated with chemotherapy live significantly longer than untreated dogs, and chemotherapy is well tolerated in most dogs. Only a minority develop significant toxicity.

Other Options

If referral to an oncologist and chemotherapy are declined, single-agent treatment with steroids (ie, prednisone) is an option. Prednisone should not be started before chemotherapy because the chemotherapy response rate may decrease. Prechemotherapy steroid use is associated with shorter remission and survival times because multidrug resistance may be induced.1 If staging tests are performed after the patient receives prednisone, higher stage patients may appear to be lower stage (ie, down-stage). In addition, making a diagnosis or staging diagnostics may be difficult or impossible, as some dogs go into complete remission on prednisone.

Relapse

Lymphoma is not a curable cancer, even though it is treatable and remission rates are high. Most lymphoma patients relapse as tumor clones that are more resistant to chemotherapy emerge or because of the survival-of-the-fittest lymphoma cells. Inadequate chemotherapy dosing or frequency or failure to achieve high chemotherapy concentrations at certain sites (eg, CNS) may also cause relapse.1

Prognosis Points

Phenotype is the best independent prognostic factor; prognosis is worse with T cell than B cell.1

Multiagent CHOP protocols are the most successful, with complete remission rates of more than 80% and remission durations of 6 to 12 months.1-3

Typical response rates with prednisone as a sole therapy are 50%, with median duration of 2 to 3 months.1-3

Without chemotherapy, the prognosis for lymphoma is poor (ie, median survival time of 1 month).1

Conclusion

Lymphoma is one of the most successfully treated cancers in dogs, and many patients outlive animals with other noncancerous diseases (eg, kidney, heart, liver). Dogs treated with chemotherapy live significantly longer than untreated dogs, and most dogs tolerate chemotherapy well.1,3,4 Prognostic factors (see Prognosis Points) cannot predict an individual’s response, and lymphoma is typically treatable and a rewarding treatment for the patient, client, and veterinary team.

This article originally appeared in the October 2017 issue of Veterinary Team Brief.