Canine Idiopathic Inflammatory CNS Disease

Richard A. LeCouteur

Profile

Definition

Inflammatory central nervous system (CNS) diseases are a group of sporadic inflammatory diseases that affect the brain and/or spinal cord in the absence of an infectious cause (ie, pathogen-free).

Based on histopathologic findings, 3 distinct forms of inflammatory CNS disease have been identified in dogs:

Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis (GME): Canine GME is the current term for an idiopathic CNS disease (most likely first described in 1936). GME still attracts a confusing and lengthy number of synonyms reflecting changes only in immunologic terminology (eg, inflammatory reticulosis, lymphoreticulosis, neoplastic reticulosis).

Necrotizing meningoencephalitis (NME): Canine NME was originally recognized in dogs in the U.S. in the 1970’s as a breed-specific disease of pug dogs (colloquially known as “pug dog encephalitis”). Since 1989, based on morphologically defined lesion patterns and histology, NME has been recognized in other small-breed dogs, including Maltese, Chihuahua, Pekinese, Boston terrier, Shih Tzu, Coton de Tulear, and papillon breeds.

Necrotizing encephalitis (NE): Canine NE was first described in 1993 in Yorkshire terriers and has been reported in other breeds, including French bulldogs.

Signalment

Age

GME affects dogs older than 6 months of age, and is most prevalent in dogs between 4 and 8 years of age.

Onset of NME is 6 months to 7 years of age, with a mean onset age of 29 months.

NE typically manifests between 4 months and 10 years of age, with 4.5 years as a mean onset age.

Breed & Sex Predilection

GME affects all sizes and breeds of dogs (with toy and terrier breeds overrepresented), whereas NME and NE affect predominantly small-breed dogs.

Both males and females are affected, although females may be at higher risk for developing the disease.

CNS = central nervous system; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; GME = granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis; NE = necrotizing encephalitis; NME = necrotizing meningoencephalitis; PCR = polymerase chain reaction

Causes

Obscure, although an autoimmune or immune-mediated/immune-dysregulatory cause is suspected.

PCR-based screening for viral DNA (eg, herpes, adeno- or parvoviruses) has been negative.

Pathophysiology

Suggested possible mechanisms include autoimmune encephalitis induced by anti-GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) antibodies in CSF and T-cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity mechanisms.

Signs

Signs of neurologic dysfunction reflect the location of the lesion(s) within the CNS.

Multifocal involvement of the cerebrum, brainstem, cerebellum, and spinal cord (GME only) is common.

Clinical signs of GME may include visual disturbances (ie, the ophthalmic form of GME affects the optic nerve), cranial nerve deficits (particularly central vestibular signs), seizures, apparent cervical pain, ataxia, and paresis.

NME and NE frequently affect the forebrain, resulting in abnormal mentation, seizures, blindness, circling, and behavior changes, or brainstem, resulting in cranial nerve deficits, changes in mentation, and difficulty walking.

Diagnosis

Definitive Diagnosis

A tentative antemortem diagnosis may be based on analysis of a combination of the patient’s:

Signalment, history, and clinical signs

Neurologic examination findings

Blood analysis results

Infectious disease titers (eg, Toxoplasma, Neospora, fungal organisms, canine distemper)

CSF analysis (including culture and PCR analysis)

Advanced imaging (CT and MRI)

Neurologic signs, CSF analysis results, and neuroimaging findings will vary with intensity and location of pathologic lesions.

Definitive antemortem diagnosis is based on characteristic findings on histopathology of brain and/or spinal cord tissue obtained by surgical biopsy.

Definitive postmortem diagnosis is based on characteristic findings on histopathology of brain and spinal cord.

Possible Causes of Brain Dysfunction in Dogs

Degenerative

Lysosomal storage diseases

Leukodystrophy/spongy degeneration

Cognitive dysfunction syndrome

Anomalous/Developmental

Congenital hydrocephalus

Caudal occipital malformation

Intracranial arachnoid cyst

Metabolic

Hepatic encephalopathy

Renal-associated encephalopathy

Hypoglycemic encephalopathy

Electrolyte-associated encephalopathy

Endocrine-related encephalopathies

Encephalopathy associated with acid-base disturbances

Mitochondrial encephalopathy

Neoplastic

Primary brain tumors

Secondary brain tumors

Nutritional

Thiamine deficiency

Inflammatory/Infectious/Immune-Mediated

Bacterial meningoencephalitis

Fungal encephalitis

Viral meningoencephalitis

Protozoal meningoencephalitis

Rickettsial meningoencephalitis

Verminous meningoencephalitis

Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis

Necrotizing meningoencephalitis

Necrotizing encephalitis

Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis

Toxic

Pyrethrins, lead, methylxanthines, zinc phosphate, & metaldehyde

Vascular

Ischemic encephalopathy

Hemorrhagic encephalopathy

Differential Diagnosis

See Box for other causes of focal and multifocal CNS dysfunction of dogs.

Laboratory Findings

CSF from dogs with inflammatory CNS disease is usually abnormal, although normal CSF may be present (particularly if corticosteroids have been administered up to 6 weeks prior to CSF collection).

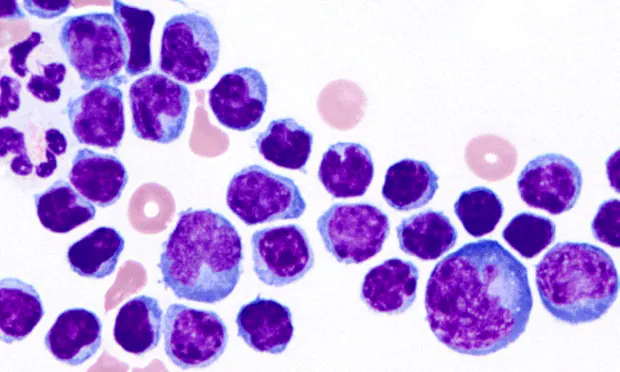

Typical findings consist of an elevated total nucleated cell count and elevated CSF protein. Lymphocytes are the predominant cell type, with smaller numbers of neutrophils and macrophages present (Figure 1).

Infectious causes of CSF abnormalities should be considered, and culture, serologic testing, electrophoresis, or PCR analysis (of CSF and/or serum) for the presence of infectious agents may be appropriate (eg, canine distemper virus), although results of these tests are unlikely to contribute to a diagnosis.

Imaging

Characteristic findings on MRI include asymmetric, bilateral (often multifocal) lesions in the forebrain, brainstem, and/or spinal cord (Figure 2). These lesions variably enhance with intravenous contrast administration. Cystic areas may be seen in areas of the brain that are necrotic.

The classical lesions in GME, NME, and NE may be distinctly different based on both distribution pattern and microscopic lesions. While this information may be helpful in differentiating between the 3 forms of inflammatory CNS disease, it may not be possible to differentiate GME, NME, and NE based on imaging characteristics alone (except that spinal cord involvement is only present with GME).

Transverse, FLAIR MRI at the level of the midbrain and cerebral hemispheres of a 4-year-old, castrated male Maltese with acute onset of mild obtundation and generalized ataxia. Note the localized hyperintensity of the white matter throughout the cerebral cortex, with bilateral periventricular edema. Ill-defined multifocal hyperintensity is also identified in the brainstem. These findings are consistent with a diagnosis of GME.

Postmortem Findings

A unique histopathologic appearance is present in each of the inflammatory CNS disorders.

GME is characterized by a unique angiocentric granulomatous encephalitis consisting of a perivascular accumulation of macrophages often intermixed with lymphocytes and plasma cells. Three major patterns of histologic lesion distribution in the brain and spinal cord have been described for GME:

The disseminated form, in which the most intense lesions occur in the upper cervical spinal cord, brainstem, and midbrain, often with less severe extension involving white matter of the rostral cerebrum (Figure 3).

GME. Disseminated form of GME with an angiocentric expansive infiltration of macrophages sometimes mixed with lymphocytes and a few plasma cells. (_H&E stain, 130×).

A disseminated form with angiocentric expansion forming multiple coalescing mass lesions of similar distribution.

A focal form, in which single discrete mass lesions occur in either the spinal cord, brainstem, midbrain, thalamus, optic nerves, or cerebral hemispheres, without dissemination. It remains contentious whether this form is a neoplastic rather than an immunoproliferative process.

NME has both a characteristic anatomic distribution pattern and unique histologic lesions:

Gross lesions occur as asymmetrical, multifocal bilateral areas of either acute encephalitis or chronic foci of malacia, necrosis, and collapse of hemispheric gray and white matter decreasing in intensity rostrocaudally.

Histologically, there is a unique combination of focal meningitis and polio- and leukoencephalitis of adjacent white matter. The lesions are intensely inflammatory with meningitis and parenchymal histiocytic, microglial infiltrates accompanied by perivascular cuffing of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Coexisting with chronic lesions can be acute nonsuppurative encephalitis in the hippocampus, septal nuclei, and thalamus. Usually, few inflammatory lesions are present in the cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord (Figure 4).

NME. Intense nonsuppurative meningitis with polioencephalitis and necrotizing leukoencephalitis. The lesions are intensely inflammatory with parenchymal histiocytic, microglial infiltrates accompanied by perivascular cuffing of lymphocytes and plasma cells. (_H&E stain, 110×)._

In canine NE, the large focal asymmetric bilateral malacic necrotizing lesions are confined mostly to the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres.

There is an intense histiocytic, microglial, and macrophage cellular infiltrate with loss of white matter and thick perivascular lymphocytic cuffing.

Other areas have acute exudation, severe edema, necrosis, and eventual cyst formation, with a dramatic gemistocytic astrogliosis, histiocytes, and gitter cells intermixed with thick perivascular lymphocytic cuffing.

Characteristically, the overlying cortex and meninges are not involved. Multifocal intense inflammatory cell infiltrates of macrophages with dramatically thick perivascular lymphocytic cuffing are seen in the midbrain, brainstem, and cerebellum (Figure 5).

NE. Intense histiocytic, microglial, and predominant macrophage cellular infiltrate with extensive destruction and loss of white matter, a characteristic proliferation of reactive astrocytes and thick perivascular lymphocytic cuffing. (_H&E stain, 265×)._

Treatment

Medical

Therapy is based on the use of immunomodulatory drugs at immunosuppressive doses.

The most common therapy utilized is corticosteroids. Dogs often have a favorable response to corticosteroid monotherapy, but response may be temporary.

Other immunomodulatory drugs may be used if the dog does not tolerate corticosteroids, to reduce the dose of corticosteroids, or if there is inadequate clinical response to corticosteroids. Many drugs have been recommended, including:

Cyclosporine

Procarbazine

Lomustine (CCNU)

Leflunomide

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)

Azathioprine

Cytosine arabinoside

All have been used by different authors in relatively small numbers of patients. There is no published evidence of the risks and/or benefits of these treatments when compared to the use of immunosuppressive regimens of corticosteroids alone.

The author recommends starting treatment with immunosuppressive doses of prednisone, giving the patient:

1.5 mg/kg Q 12 H for 3 weeks

1 mg/kg Q 12 H for 6 weeks

0.5 mg/kg Q 12 H for 3 weeks

0.5 mg/kg Q 24 H for 3 weeks

0.5 mg/kg every other day indefinitely

After the first 4 to 6 weeks of prednisone therapy, cytosine arabinoside may be added at 3 to 6 week intervals (administered as a subcutaneous injection, 50 mg/m2 Q 12 H for 2 consecutive days).

Precautions

Adverse effects of long-term high-dose corticosteroid therapy include polyuria/polydipsia, polyphagia, weight gain, hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal ulceration, pancreatitis, and iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism.

Adverse effects of cytosine arabinoside are dose dependent, including myelosuppression, vomiting, diarrhea, and hair loss.

Activity

No exercise restrictions are recommended.

Client Education

Clients should be informed that there is no definitive treatment for inflammatory CNS diseases of dogs. Therapy is aimed at suppressing the dog’s immune system for as long as possible.

Follow-Up

Patient Monitoring

Regular rechecks (suggested at monthly intervals or as needed) should be performed to assess progress of disease and adverse effects of medications.

Repeat CBCs, serum biochemical profiles, urinalysis, CSF analysis, and advanced imaging may be necessary.

In General

Relative cost

Diagnosis and long-term management are costly due to the need for specialized diagnostic procedures, immunomodulatory drug maintenance, and repeated assessments ($$$$$).

Prognosis

Prognosis for dogs with inflammatory CNS disease is poor, and most affected dogs eventually die or are euthanized. Some survive only a short period of time, while others have a more prolonged clinical course from 6 months to, rarely, years.

Future Considerations

Research to date on canine inflammatory CNS diseases and the nature of the histo-pathologic lesions suggest the likelihood of an autoimmune or immune-mediated/immunedysregulatory disease.

In humans, many autoimmune diseases have strong associations with certain MHC genotypes and this information may be used to assist in diagnosis or patient counseling.

It is now possible to determine the MHC haplotype of dogs, and some disease associations with MHC haplotype in dogs have already been demonstrated. Assessment of MHC haplotype in dogs with GME may help determine if there is a genetic component to disease susceptibility and development.