Glaucoma comprises a group of diseases that ultimately result in optic nerve head circulation damage, retinal ganglion cell death, and irreversible blindness.1-3 It is a common and painful cause of blindness in dogs, affecting nearly 0.9% of purebreds in North America.4

Related Article: Acute Primary Angle-Closure Glaucoma

Levels of CareThe goal of the practitioner should be to determine:

Whether glaucoma is the correct diagnosis

Whether glaucoma is primary or secondary

Whether it is acute or chronic.

Once these determinations are made, a treatment plan can be developed.

DiagnosisA glaucoma diagnosis is established by measuring intraocular pressure (IOP) in all red eyes. IOP varies with species, age, breed, time of day, method of restraint, tonometrist, and tonometer. Younger dogs have a higher normal IOP than older ones. The normal IOP range should be established by the tonometrist; in our practice, using a Tono-Pen (reichert.com), we consider normal IOP to be between 8 and 20 mm Hg. Routine screening of dog breeds predisposed to primary glaucoma makes purchase and use of a tonometer cost-effective.

Primary or SecondaryPrimary glaucoma is caused by abnormal anatomy of the iridocorneal angle and usually occurs between 3 and 9 years of age, rarely in mixed breed dogs. Glaucoma can also be secondary to other eye diseases and conditions, including anterior lens luxation (inherited in at least 45 breeds, including most types of terriers, basset hounds, beagles, and Arctic circle breeds2), chronic anterior uveitis, chronic long-standing cataracts, prior cataract surgery, retinal detachment, hyphema, and intraocular neoplasia. It is not always obvious whether glaucoma is primary or secondary, but effective treatment varies depending on underlying cause.

Acute or Chronic

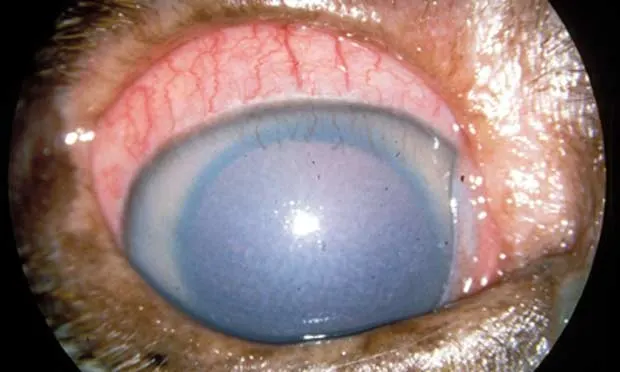

Clinical signs of acute congestive glaucoma (Figure 1) include diffuse corneal edema, scleral injection, mydriasis, and diminished or loss of vision. Diffuse corneal edema often makes fundic examination difficult. The eye will likely be blind if IOP is greater than 40 mm Hg and may have an inconsistent dazzle response and consensual pupil light reflex (PLR). Generally, if IOP has been greater than 50 mm Hg for more than 3 days, the potential for vision is negligible. Because it is usually unknown how long IOP has been elevated, always try toimmediately decrease it.

Figure 1: An eye with acute congestive glaucoma. There is diffuse corneal edema, scleral injection, mydriasis, epiphora, corneal vascularization, and conjunctival hyperemia of the nictitans.

Clinical signs of chronic glaucoma (Figure 2) include buphthalmia, Haab’s striae, lens subluxation or luxation, fundic changes, including optic nerve cupping, retinal vascular attenuation, and tapetal hyperreflectivity (Figure 3). Chronically affected eyes do not regain sight.

Figure 2: A husky with bilateral chronic glaucoma. Both eyes are buphthalmic, have extreme mydriasis, and the lenses are posteriorly luxated and located in the ventral vitreous.

Figure 3 (A) is a normal canine fundus; (B) is a canine fundus with chronic glaucoma showing optic nerve cupping, tapetal hyperreflectivity, and retinal vascular attenuation.

When to Consider ReferringTime is imperative when managing and/or referring a glaucoma case. If you do not have a tonometer or are unsure of diagnosis, cause (primary or secondary), or chronicity, call a veterinary ophthalmologist for advice and/or referral. Evaluation through digital palpation of the globe alone is not acceptable. If there is good comfort level with your diagnosis and appropriate medications are accessible, then initiate treatment immediately, even prior to referral. The client must understand that surgical intervention combined with medications may be necessary to effectively manage glaucoma and that irreversible blindness may ensue, even when all appropriate interventions are employed.

The Referral ProcessWhen calling an ophthalmologist for advice or referral, start the conversation with the dog’s signalment. Describe both eyes (some subtle signs may indicate a problem in the seemingly unaffected eye) and provide medications used and dose information. Inform the client of the approximate cost of an initial referral examination, which will be provided by the veterinary ophthalmologist. Typically, a referral letter is generated following the evaluation. A complete ophthalmic examination includes:

● Direct and consensual PLRs● Schirmer’s tear test● IOP measurement● Fluorescein staining● Evaluation of the extraocular/intraocular structures, including slit lamp evaluation and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy.

If medical therapy is unsuccessful, surgical options for animals that have vision or the potential for vision include traditional or endolaser diode laser cycloablation, gonioimplants or glaucoma valves, or a combination of both.

When Referral Is Not an OptionBe prepared—medical management of glaucoma can be frustrating. Educating clients is the key to securing their tolerance and patience. Even after appropriate and aggressive medical management, glaucoma can progress. It can become recalcitrant to therapy if the patient is not periodically reevaluated with medications adjusted to maintain IOP in the safe range. For my well-managed glaucoma patients, a safe IOP is below 20 mm Hg. If IOP rises into the low 20s or higher and medications are at a maximum, call a veterinary ophthalmologist. Intraocular pressure in dogs does not always slowly increase over time, but pressure spikes frequently occur that can be blinding. Treating and/or preventing these spikes is of utmost importance. Monitor IOP once or twice a week for the first month to ensure that therapy is adequate.

Treatment options by stage are discussed in Table 1. Once IOP is consistently below 20 mm Hg for a 12- to 24-hour period, medical management (Table 2) is continued and rechecked periodically. If IOP does not drop significantly or is still above 30 mm Hg, it is unlikely that continued medication will decrease the IOP. If the animal is blind and IOP is above 30 mm Hg, pain is likely and a fair suggestion to the client is enucleation or ciliary/chemical ablation to alleviate discomfort. Another palliative surgical procedure is evisceration with intrascleral prosthesis placement; this procedure is usually only available through a veterinary ophthalmologist.

Pain ManagementGlaucoma pain results from elevated IOP and is proportional to its magnitude. The only way to control the pain is to decrease IOP. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications are contraindicated with primary glaucoma; they can elevate IOP in canine patients and will not diminish pain. Humans with glaucoma have migraine-like headaches, nausea, vomiting, and profuse sweating. Animals with glaucoma are also in significant pain; however, their stoic natures often hide their discomfort. Tramadol may be used to help with pain; however, it has not been evaluated for this purpose in glaucoma.