A 12-year-old, 10.5-lb (4.8-kg), spayed poodle crossbreed was presented with acute, progressive spinal pain of 10 days’ duration. Physical examination was unremarkable. Neurologic examination showed the following.

Mentation: Bright, alert, and responsive; friendly

Cranial nerves: Normal

Spinal reflexes: All limbs normal, cutaneous trunci reflex and perineal reflex present

Postural reactions: Delayed paw replacement in both pelvic limbs, normal paw replacement in both thoracic limbs

Gait: Ambulatory with mild paraparesis and intermittent proprioceptive ataxia, especially at a slow walk compared with a fast walk or trot

Palpation: Pain response at the thoracolumbar junction on palpation; questionable pain response with tail flexion

The remainder of the neurologic examination, including cervical range of motion, was normal.

Neuroanatomic lesion localization: T3-L3 myelopathy

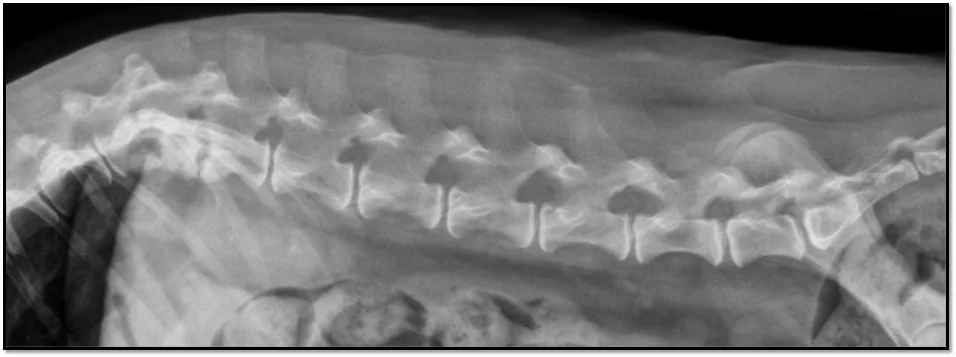

Plain lateral thoracolumbar spinal radiography was performed to pursue an etiology for the spinal pain.

Lateral radiograph

The T12-T13 (black arrow) and T13-L1 (white arrow) vertebral end plates were sclerotic and irregular with areas of lysis, and the T12-T13 intervertebral disk space appeared collapsed with possible subluxation of the articular processes. A second view would be needed to evaluate lateral subluxation.

Radiographs were suggestive of discospondylitis. Discospondylitis is most commonly diagnosed in young, large-breed hunting dogs but should be considered in any patient with acute, focal spinal pain with or without myelopathy. Bacterial and fungal organisms can cause discospondylitis. Staphylococcus spp, Streptococcus spp, and Pasteurella spp are commonly reported bacterial etiologies; Aspergillus spp is the most commonly reported fungal etiology in dogs. Cultures of urine, blood, or disk material may aid in diagnosing the causative agent.

Following diagnosis of discospondylitis, testing for Brucella canis is important due to zoonotic potential and is encouraged in patients with a history of travel to areas with endemic infection, as well as in patients with a history of or anticipated breeding potential.1 B canis is currently considered endemic in the southern United States and Mexico and is a reportable disease in some US states and in many countries. Local regulations for reporting should be followed.