Ask the Expert: What types of behaviors might be considered normal or abnormal among cats in a multicat household?

Terminology

Veterinary professionals and pet owners are encouraged to use the terms engaging or protective, which emphasize the tendency for cats to follow natural survival instincts (see Table 1), instead of the terms normal or abnormal. Use of the terms bully, victim, aggressor, and aggression are also discouraged, as these terms are subjective and anthropomorphic.

Background

Social harmony among cohabitating cats is an important contributor to mental and physical well-being; disharmony is often underrecognized and not appropriately acknowledged by owners and veterinary professionals. Intercat tension is defined as poor tolerance of other cats and lack of friendly interactions of 1 or more cats toward a cohabitating cat. The Feline Veterinary Medical Association (formerly known as The American Association of Feline Practitioners) has published guidelines to help inform this issue.1

Social Structure

Understanding feline social structure is essential for assessment of whether disharmony exists in a multicat household. Cats do not use a typical hierarchical group dynamic but instead have a fluid, context-dependent social structure dictated by availability of resources, individual temperaments, life experiences (particularly during the early developmental stage [2-9 weeks of age]), and, to some extent, relatedness of individuals.2 Although social connectedness is not essential for cats (ie, cats are not socially obligate), many cats form strong social bonds with each other and/or their human companions.3

Shared scent is important for reducing arousal and agonistic behaviors, and visual signals (eg, slow blinking, gaze aversion, certain body postures) can help maintain harmony.1,2 Cats are also adept at using social distancing via territory negotiation and avoidance rather than direct appeasement (eg, submissive postures [eg, exposing the belly, tail tucking]).1,2

Cats often form affiliative clusters within households and may defer to or dominate other group members in a weblike set of relationships (see Pet Owner Guidance).1,2 Intercat dynamics can be context dependent. For example, one cat may control access to food but defer to another cat over a preferred bed.

There is no evidence that intercat tension arises due to struggles with dominance. Intercat tension mostly occurs because of limited resources or stress caused by changes in social structure (eg, addition of a new cat, influence of outside cats, pain, illness). Typically, cats do not establish a rigid hierarchy, and disharmony can persist indefinitely.1

Pet Owner Guidance

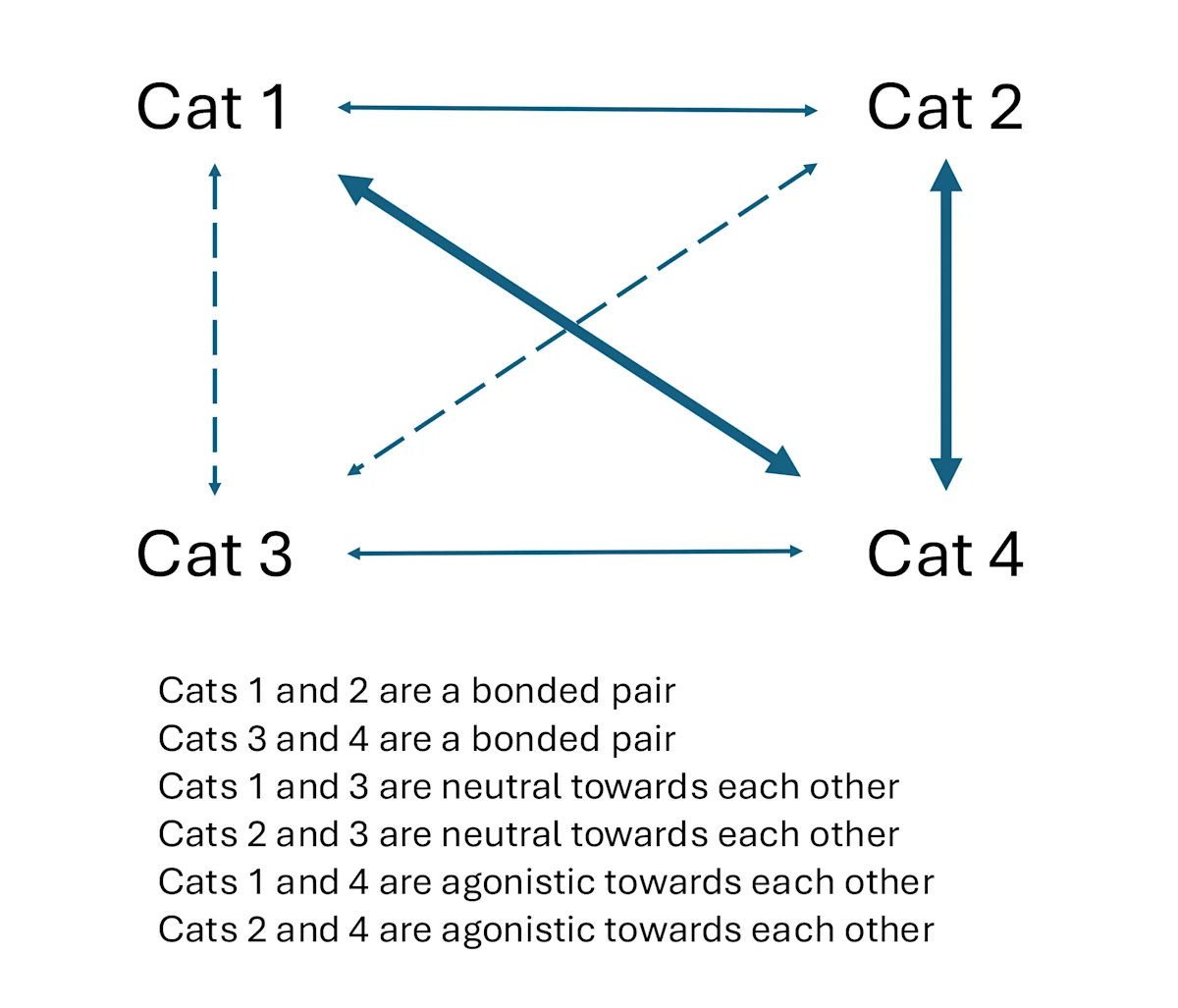

When dealing with intercat aggression, owners should first establish a social map of the feline dynamics in the household to identify which cat displays affiliative, tolerant, or agonistic behaviors and to which cat the behavior is directed. Owners should be instructed to observe and record the cats’ daily interactions, classifying each according to the categories outlined in Table 1, as well as the frequency and intensity of these interactions. Using the owner’s observations, a diagram can be constructed of the household cat population, with solid lines connecting bonded pairs, dotted lines connecting cats that tolerate or are neutral toward each other, and bolded lines connecting cats that are in conflict (Figure 1). The diagram can help guide resource distribution, as well as where separation and, potentially, reintroduction protocols may be useful.

FIGURE 1 Diagram based on owner observations showing the relationships among 4 cats

Owners should also be counseled to look for repeated patterns of behavior, as differentiating rough play from true conflict behavior can be difficult. Both situations may involve wrestling, chasing, pouncing, batting, mouthing, and occasional vocalization.

Play Activity

Cats engaged in play activity typically take turns chasing and being chased, claws are typically sheathed, and biting does not break the skin. Muscle tone and facial expressions are relatively relaxed, and there are frequent pauses in activity. Once play has ceased, the cats often stay in proximity to each other.

True Conflict Behavior

Conflict behavior is typified by one cat consistently acting in a protective manner. Vocalizations and hissing escalate, and evidence of physically rough behavior (eg, fur clumps, bite and scratch marks) may be observed. Body language tends to be tense, with dilated pupils, stiff body position, and ears flattened to the side or back of the head. Avoidant or repellent behaviors are usually ongoing, with one or more cats showing some inhibition of normal activities.

Undesirable behaviors stemming from lack of enrichment present in a nearly identical manner as those caused by primary behavior disorders, with only nuances differentiating the two. Follow these steps to pinpoint the telltale signs that hint at the true underlying problem.

Management

As issues often begin with introduction of a new cat to the household, thoughtful adoption choices; a slow, deliberately paced introduction process; and ongoing adjustments to the home environment may be needed to maintain social harmony.4 Owners should be encouraged to provide plenty of resources dispersed throughout the environment to create visual barriers. Vertical spaces and safe zones should also be provided to allow cats the opportunity to observe the space and enjoy undisturbed rest periods.

Active cats may need owner-directed play sessions, especially in cases in which companion cats are elderly, unwell, or not willing to participate in play activities. Owners should also consider adding a bell to the collar of cats engaged in agonistic behavior so other cats can employ avoidance behaviors if needed. In some circumstances, periods of daily separation should be considered to give all cats adequate time to rest and access resources.

The likelihood and potential severity of harm to cats and humans should be assessed. Cats displaying overtly agonistic behavior should be distracted with toys, or a visual barrier should be used. Owners should be discouraged from physical intervention (ie, separating the cats), as serious injury can occur. Temporary measures to reduce risk (eg, physical separation of cats into different rooms) may be necessary, followed by a period of slow reintroduction.

If external cats are contributing to household disharmony (eg, redirected aggression), the owner should be encouraged to keep their cats indoors or confined to cat-specific patios (ie, catios). External cats should not be able to enter the home via cat flaps, and visual blocking (eg, screens, opaque window film) should be considered.

Maintenance

Maintenance strategies in the home should include implementation of The Five Pillars of a Healthy Multicat Environment and may also include feline synthetic pheromones, calming nutraceuticals, psychotherapeutic medications, and/or referral to a veterinary behaviorist.5 For intractable situations, a diplomatic but frank discussion addressing rehoming of one or more cats may be necessary.

The Five Pillars of a Healthy Multicat Environment

Safe places for each cat

Multiple, separated key resources (eg, food and water bowls, litter trays, vertical perches, beds)

Opportunities for play and natural predatory behavior

Positive, consistent, predictable human interactions

Environment respectful of feline senses (eg, avoidance of loud noises and strong odors [eg, pungent disinfectants])

While taking a patient history or observing behavior in the examination room, clinicians are presented with a unique opportunity to spot behavioral red flags—sometimes before the client recognizes a problem exists. Unlike with other medical issues, being too direct about behavioral concerns may make some clients feel defensive or even hostile.

The key to having a productive conversation instead of backing a client into a corner is in taking the right approach.

Ask open-ended questions to better understand the client’s perspective and why they might be reluctant to see a problem.

Approach the situation without judgment, and focus on how the patient may be feeling rather than assigning blame.

Get more tips on how to navigate this tricky situation in this article on Managing Clients Who Deny Behavior Issues in Their Pet.