Acute Primary Angle-Closure Glaucoma

ProfileDefinitionAcute glaucoma is a group of potentially blinding disorders unified by a common theme: high (>_ 25 mm Hg) intraocular pressure (IOP) damages the optic nerve. Acute glaucoma is most frequently seen as primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) in dogs with drainage angle abnormalities (goniodysgenesis or narrow drainage angles, Figure 1) or secondary to other ophthalmic diseases such as anterior uveitis, hyphema, intraocular neoplasia, or anterior lens luxation (Figure 2). This article will focus on PACG.

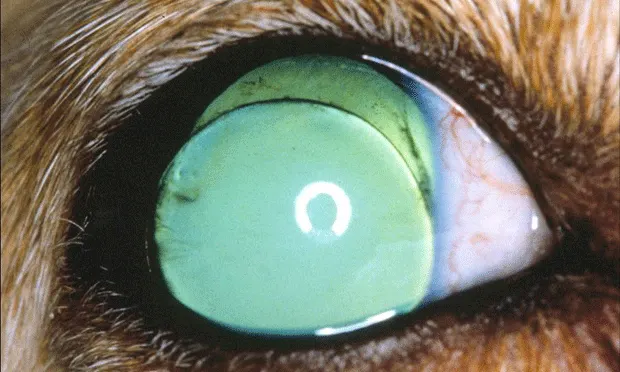

Figure 1. A Siberian husky with acute primary angle-closure glaucoma. Note the mydriasis and conjunctival hyperemia.

Figure 2. Anterior lens luxation in a terrier dog. Note the position of the lens in front of the iris and the aphakic crescent dorsally.

Genetic Implications. Complex inheritance pattern with strong breed predispositions (see Signalment)

Incidence/Prevalence. One in 119 dogs has some form of glaucoma in its lifetime.

Geographic Distribution. Worldwide

SignalmentBreed predilection.Goniodysgenesis: Arctic circle breeds (Akita, Alaskan malamute, Norwegian elkhound, Samoyed, Siberian husky), bassett hound, Bouvier des Flandres, flat-coated retriever, poodles (all varieties), shar-pei, Shiba Inu, spaniels (English cocker and English springer)

Narrow drainage angles: American cocker spaniel, Boston terrier, chow chow, golden retriever, Leonberger, Welsh springer spaniel

Age and range.Typically 4 to 9 years of age

Gender. 2:1 female to male ratio

Causes & Risk FactorsBreed, age, and sex are significant risk factors. Acute PACG attacks often occur at night or are precipitated by stress, excitement, or other events that create a mid-range to dilated pupil.

PathophysiologyProposed mechanism for acute PACG (Figure 3):

Drainage angle malformations hold the peripheral iris in abnormal proximity to the cornea.

Stress or excitement causes the pupil to become mid-range, allowing the less taut iris to come into greater contact with the anterior lens surface.

Increased pulse pressure in the choroidal blood vessels pushes against the vitreous and aqueous humors in the posterior chamber, forcing more aqueous humor through the pupil and into the anterior chamber.

The compromised drainage angle prevents this additional fluid from escaping the anterior chamber and creates a "reverse ball valve" in which the iris is forced into greater apposition with the lens, which prevents additional aqueous from returning to the posterior chamber.

This process repeats until IOP reaches a physiologic maximal value of about 50 to 80 mm Hg.

Figure 3. Proposed mechanism of acute PACG in dogs: In short, increased pulse pressure in the choroid forces aqueous humor in the posterior chamber against the posterior peripheral iris (1) and through the pupil (2) into the anterior chamber. Preexisting drainage angle abnormalities prevent this excess aqueous humor from leaving the eye (3), resulting in increased contact between the iris and the anterior lens capsule (4, “reverse ball valve”). This continues until IOP reaches about 50 to 80 mm Hg. Modified with permission from Slatter’s Fundamentals of Veterinary Ophthalmology, 4th ed. Maggs DJ, Miller PE, Ofri R (eds)—St. Louis: Elsevier, 2008, pp 230-257.

The attack may spontaneously resolve if increased IOP can force the drainage angle open or cause the peripheral iris to "slide" off the curved anterior lens capsule, thereby disrupting the ball-valve effect. Sustained IOP increases, however, mechanically distort and reduce blood flow to the optic nerve, thereby interfering with the flow of critical growth factors and nutrients to the retinal ganglion cells. Death of these cells can lead to a vicious cycle-dying ganglion cells release glutamate and other neurotoxins that kill adjacent, previously healthy ganglion cells, even if IOP is returned to normal.

SignsHistory. An acutely red, painful eye, often with a cloudy cornea and potentially rapid vision loss. Occasionally the clinical signs are intermittent and spontaneously resolve. Signs of general malaise (eg, lethargy, anorexia) may be present as well.

Physical Examination. May present unilaterally, but both eyes are at risk. IOP is typically > 25 mm Hg (usually much greater). Other signs include engorged episcleral vessels, diffuse corneal edema, a fixed and relatively dilated pupil, and pallor/cupping of the optic nerve head (seen with ophthalmoscopy). Vision is usually, but not always, absent.

Pain IndexAcute glaucoma creates considerable, but poorly localized, pain involving the head and orbit. Humans compare this pain to a migraine headache, and dogs undoubtedly experience a comparable sensation. In addition, lethargy and anorexia may be signs of pain.

Diagnosis

Definitive DiagnosisIncreased IOP and presence of the appropriate clinical signs

Differential DiagnosisImproper tonometric technique or an uncooperative patient can provide falsely high IOP readings. In acute PACG there are no other obvious causes of the glaucoma (lens luxation, hyphema, anterior uveitis) other than those involving the drainage angle (not visible without gonioscopy). Ultrasonography may help identify whether abnormalities other than glaucoma (eg, retinal detachment, intraocular tumors, etc) are present.

TreatmentInpatient or OutpatientUsually inpatient until IOP is stabilized

Medical

Apply 1 to 2 drops of 0.005% latanoprost (Xalatan; Pfizer, www.xalatan.com) to affected eye and measure IOP in 1 to 2 hours.

If IOP is not down in 2 hours administer:

Mannitol: 1 to 1.5 g/kg slow IV over 20 minutes or 5 to 7.5 mL/kg of a 20% solution

Oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (CAI): Methazolamide or dichlorphenamide, 2.2 to 4.4 mg/kg PO Q 8 to 12 H or topical CAI: 2% dorzolamide (Trusopt, www.merck.com) or 1% brinzolamide (Azopt, www.alcon.com) Q 8 H

2% pilocarpine: 1 drop every 10 minutes for 30 minutes, then Q 6 H

Surgical (typically referral procedures)

Eyes with the potential for vision: Laser cyclophotocoagulation, endocyclophotocoagulation, cyclocryosurgery, and/or gonioimplantation

Blind eyes (ie, no vision for at least 1-2 weeks after onset of vision loss): Consider intrascleral prosthesis or enucleation

ActivityRestricted until IOP is stable and any surgery sites have healed

Client EducationGlaucoma is often blinding but there is some hope that vision can be preserved depending on the magnitude as well as duration of the IOP increase. Eyes with chronic IOP increases should be regarded as painful even if the animal behaves relatively normally. Surgically lowering IOP in these eyes invariably improves the dog's quality of life. The client should also be aware that the fellow normotensive eye is at considerable risk of developing acute glaucoma (see Prevention).

Medications

DrugsSee above.

ContraindicationsDo not use atropine or tropicamide.

Precautions

Heat and/or filter mannitol to prevent IV administration of crystals.

Systemic CAIs (methazolamide, dichlorphenamide) can induce hypokalemia and metabolic acidosis.

Dogs that have received mannitol or a systemic CAI can have hydration or electrolyte disturbances that impact general anesthesia.

InteractionsMost topical antiglaucoma drugs are synergistic with one other. Demecarium bromide is an organophosphate-be careful with drugs that have a comparable mechanism of action.Follow-Up

Patient MonitoringMeasure IOP several times a day initially, then less frequently as it stabilizes. When treating for glaucoma, keep IOP below 20 mm Hg. It is not uncommon for dogs that initially respond to medical management to become nonresponsive within 6 months and require surgery.

PreventionThe fellow normotensive eye in dogs with acute PACG has a 50% chance of experiencing an overt attack of glaucoma within 8 months. Topical therapy with 0.5% betaxolol Q 12 H or 0.125% to 0.25% demecarium bromide Q 24 H along with a topical corticosteroid Q 24 H (at night) has been shown to reduce the likelihood of an attack to 50% in 30 months.

Course & Future Follow-UpLife-long therapy is generally required if the affected eye is to retain vision. In addition, life-long follow-up is required unless an enucleation or globe-salvage procedure has been performed.

In General

Relative Cost

Inpatient medical care: $ to $$/day

Outpatient medical care: $ to $/month

Surgical care: $$$

PrognosisGuarded for preservation of vision

Future ConsiderationsMany new antiglaucoma drugs are in the pipeline and surgical procedures continue to be refined. Neuroprotective drugs may become a therapeutic mainstay in the future. n

TX at a glance

Emergency Treatment

1-2 drops of 0.005% latanoprost to affected eye

Measure IOP in 1-2 H

If IOP is not down in 2 H give:

Mannitol: 1-1.5 g/kg slow IV over 20 min or 5-7.5 mL/kg of a 20% solution

Oral CAI: Methazolamide or dichlorphenamide, 2.2-4.4 mg/kg PO Q 8-12 H or a topical CAI: 2% dorzolamide or 1% brinzolamide Q 8 H

Pilocarpine (2%): 1 drop every 10 minutes × 3; then Q 6 H

Begin prophylactic therapy for fellow eye

ACUTE PRIMARY ANGLE-CLOSURE GLAUCOMA • Paul E. Miller

Suggested Reading

Combined cycloablation and gonioimplantation for treatment of glaucoma in dogs: 18 cases (1992-1998). Bentley E, Miller PE, Murphy CJ, Schoster JV. JAVMA 215:1469-1472, 1999.Combined transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation and Ahmed gonioimplantation in dogs with primary glaucoma: 51 cases. Sapienza JS, van der Woerdt A. Vet Ophthalmol 8:121-127, 2005.Morphologic features of degeneration and cell death in the neurosensory retina in primary angle-closure glaucoma in dogs. Whiteman AL, Klauss G, Miller PE, et al. Am J Vet Res 63:257-261, 2002.Outcomes of nonsurgical management and efficacy of demecarium bromide treatment for primary lens instability in dogs: 34 cases (1990-2004). Binder DR, Herring IP, Gerhard T. JAVMA 231:89-93, 2007.The efficacy of topical prophylactic antiglaucoma therapy in primary closed angle glaucoma in dogs: A multicenter clinical trial. Miller PE, Schmidt GM, Vainisi SJ, et al. JAAHA 36:431-438, 2000.The glaucomas. Miller PE. In Maggs DJ, Miller PE, Ofri R (eds): Slatter's Fundamentals of Veterinary Ophthalmology, 4th ed-St. Louis: Elsevier, 2008, pp 230-257.The intracapsular extraction of displaced lenses in dogs: A retrospective study of 57 cases (1984-1990). Glover TL, Davidson MG, Nasisse MP, Olivero DK. JAAHA 31:77-81, 1995.