Acute Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus in Dogs

ProfileDefinitionAcute gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV) is an overdistension of the stomach with gas, fluid, or ingesta combined with rotation of the stomach on its mesenteric axis.

Systems. The stomach alone or in conjunction with the spleen can become devitalized due to distension and rotation. Collapse of the circulatory system can lead to cardiac arrhythmias and possible death. Multiple organ systems (liver, kidneys, brain) may also suffer damage due to a hypotensive state or bacteremia. Occasionally there is transient dysfunction of the esophagus.

Genetic Implications. Some families of large and giant breed dogs are thought to be at greater risk for developing GDV, especially if there is a first-degree relative (sibling, offspring, parent) with a history of at least 1 episode of GDV.1

SignalmentBreed Predilection. Great Danes, Saint Bernards, Weimaraners, Irish setters, Gordon setters and bloodhounds appear to be at greatest risk for developing GDV.<sup1, 2sup> Overall incidence of GDV in large and giant purebred dogs was reported to be 15.7% and 8.7% respectively.2 The Great Dane, assuming a longevity of 8 years, has a 42% incidence. Smaller breeds and cats are occasionally affected; dachshunds appear to be at increased risk.

Age and Range. Large and giant breed dogs greater than 5 years of age have a much higher risk factor than younger dogs.1

Gender. Male dogs, whether neutered or not, are at slightly higher risk of developing GDV than females. 2

CausesThis syndrome has a multifactorial etiology. It is presumed that gastric dilatation is the result of the animal's impaired ability to empty gas, primarily swallowed air from the environment, from the stomach and eructate when excessive gas accumulates.

Risk FactorsPersonality Traits. There appears to be a direct relationship between temperament and the tendency to develop GDV. Hyperactive animals with a fearful or "unhappy" personality are more likely to develop GDV. Stress can also precipitate GDV.<sup1, 2sup>

Body Condition & Anatomic Factors.

Thin or lean body condition (giant breeds)2

High abdominal depth (large & giant breeds)<sup3, 4sup>

High thoracic-depth-to-abdominal-depth ratio (large breeds)<sup3, 4sup>

Degree of thoracic depth-to-width ratio (Irish setters)5

Dietary Factors.

Rapidly eating large amounts of food (especially when fed once daily)

Eating out of a raised feed bowl

Feeding dry foods with fat listed as one of the first 4 ingredients

Feeding foods containing citric acid and moistening them prior to consumption

Feeding food with bone listed as one of the first 4 ingredients6

PathophysiologyGastric distension causes functional and mechanical obstruction, and relief of distension through eructation or the passage of gastric contents aborally through the pylorus is impaired. It is thought that laxity of the hepatogastric and hepatoduodenal ligaments allows enough gastric mobility to predispose to clockwise rotation of the gas-filled stomach (when viewing the animal from behind).

The short gastric vessels may become twisted, thrombosed, or avulsed. The latter can cause a hemoabdomen. Gastric distension results in decreased blood flow to the stomach wall and impairment of blood flow through the caudal vena cava and portal vein. This can result in decreased cardiac output, myocardial hypoxia, hypovolemic shock, and hypotension-leading to inadequate tissue perfusion to all organs including the heart, pancreas, kidney, stomach mucosa, and small intestine.

Cardiac arrhythmias may result from myocardial necrosis secondary to ischemia, neurohumoral factors, or toxic (endotoxin) cardiac damage. Concentrations of serum cardiac troponin I and troponin T have been recently shown to be associated with severity of ECG abnormalities.7

Cardiac and hypotensive conditions can also lead to an increased rate of endotoxin release by intestinal bacteria. Enteric bacteria and toxins move across the intestinal mucosal barrier and enter the circulatory system. Concurrent portal vein occlusion decreases the ability of the reticuloendothelial system to handle toxins and absorbed (translocated) bacteria. Hypoventilation can result from impairment of diaphragmatic movement. The spleen can become congested, thrombosed, and necrotic secondary to torsion. One report describes GDV occurring in two dogs after splenic torsion.8 There is some evidence to suggest reperfusion injury is responsible for the high mortality rates associated with GDV. 9

SignsHistory. Recent episodes of self-relieving mild to moderate gastric distension, anorexia, or occasional vomiting are reported. Restlessness, retching, and ptyalism may also be observed. Depending on the length of illness, dogs become depressed and recumbent, develop a tympanic abdomen, and exhibit apparent abdominal pain (Glasgow composite pain score 6-7). This pain score reflects a dog that has some degree of groaning, is slow or reluctant to move at times, will have some degree of discomfort when palpating the abdomen, is quiet and occasionally tense. However, in some instances, owners will not recognize any degree of discomfort in their dog at the time of presentation.

_Physical Examination._A grossly distended, tympanic stomach; abdominal pain; splenomegaly; and evidence of circulatory shock are often observed. Hyperpnea and dyspnea may also be present. Pulse deficits may be palpated.

DiagnosisDefinitive Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on history, clinical signs, physical examination findings, and radiography. A right lateral abdominal radiograph confirms the diagnosis but is postponed until after the patient is stabilized. GDV is confirmed when the pylorus is seen dorsally, cranially, and to the left of the midline and the fundus is ventrally displaced (Figure 1). The spleen is often large and located in a right dorsal position.

Figure 1. A right lateral recumbency abdominal radiograph demonstrates the movement of the pylorus dorsally (small arrow) and the fundus ventrally (large arrow).

Barium can be given per os if the position of the stomach is questionable or the presence of a foreign body is suspected. Abdominal effusion may be seen, which may indicate gastric perforation or hemorrhage from torn short gastric vessels.

Differential DiagnosisGastric dilatation without volvulus, gastric foreign body, splenic torsion, splenic/gastric neoplasia, intestinal volvulus, diaphragmatic hernia, and ileus from other causes such as peritonitis are considerations.

Laboratory FindingsMost abnormal data is nonspecific for GDV. Hemoconcentration is commonly seen. Hypokalemia is the most common electrolyte disorder detected after decompression and fluid resuscitation. Although magnesium levels should be evaluated, their relationship to cardiac arrhythmias do not appear to be important in GDV cases.10 The most common acid-base abnormality is metabolic acidosis. Plasma lactate concentration as a predictor of gastric necrosis and survival among dogs with GDV has been reported.11 Concentrations in dogs with gastric necrosis (> 6.6 mmol/L) were significantly higher than concentrations in dogs without gastric necrosis (< 3.3 mmol/L).

TreatmentInitial ManagementStomach Decompression. Traditionally, initial management includes rapid decompression of the stomach with an orogastric tube. However, bypassing orogastric intubation in favor of immediate decompression using trocarization may be a better way to initially decompress the dilated stomach.12 The best needle placement (over-the-needle catheter, 14-18 gauge) is determined by percussing the most tympanic portion of the stomach or auscultating the stomach and listening for a high-pitched sound ("ping"). After the placement of intravenous catheters and aggressive fluid therapy has begun, gastric lavage can be considered using 2 to 3 liters of saline or warm water.

Fluids. The placement of a large-bore intravenous catheter in each front leg allows rapid administration of a balanced electrolyte solution (100 ml/kg the first hour) or hypertonic 7% saline (4 to 5 ml/kg over 15 minutes).

Pain Management. An analgesic such as fentanyl (0.0005 mg/kg IV) is recommended soon after admission. After the initial bolus of fluid, fentanyl can be added to the IV fluid as a CRI of 0.02 to 0.05 µg/kg/min. A loading dose of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg IV) is followed by the addition of 60 mg of ketamine per liter of solution. Lidocaine can also be added, which helps manage pain and decreases the amount of injectable or inhalant anesthesia needed during surgery; the infusion dose is 10 to 50 µg/kg/min (2% lidocaine). However, it is preferred that some degree of flexibility be considered for adjusting fluid therapy infusion rates. This can be accomplished in a more practical manner by having at least one of the drugs (fentanyl) be administered through a syringe pump.

Additional Management. ECG monitoring is done continuously for up to 72 hours since there is a high incidence (42%) of cardiac dysrhythmias associated with GDV.13 Cefoxitin (20 mg/kg Q 8 H) is an antibiotic commonly selected for bacteremia and bacterial translocation occurring during GDV and is given perioperatively starting 20 to 30 minutes prior to surgery and repeated 3 hours later. In addition, oxygen is given through a nasal cannula as necessary.

Surgical ManagementDefinitive treatment with a gastropexy is highly recommended. Anatomic repositioning of the stomach and spleen is followed with a right-sided gastropexy. Incisional gastropexy is preferred by many surgeons over other techniques due to simplicity, speed, and predictable results.<sup14, 15sup> A splenectomy or partial gastrectomy may be indicated. An invagination technique has been described to cover areas of the stomach that are devitalized but this must be followed by a period of systemic antacid therapy to prevent ulcer formation and severe hemorrhage.16

A synthetic colloid administered during and after surgery is recommended to help maintain a normotensive state.17 Oxyglobin can be considered at a dose of 125 to 250 ml per animal.12 This is thought to enhance the blood's oxygen carrying capacity to all tissues, including the myocardium.

Postoperative Management

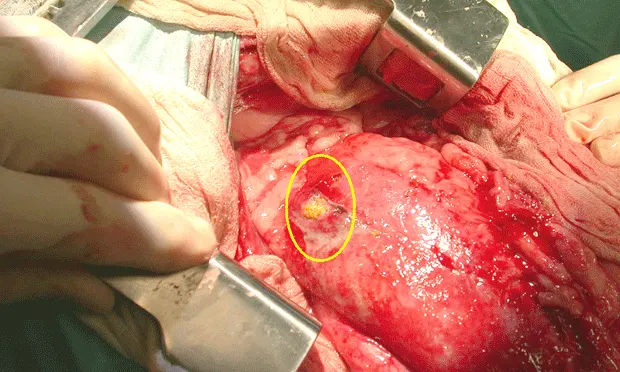

CRI of ketamine, fentanyl, and lidocaine is continued. Electrocardiographic monitoring should be done for 24 to 48 hours. Potassium chloride (40 to 60 mEq/L) should be added to crystalloids when fluid therapy is returned to maintenance levels. Since GDV patients are at risk for gastric ulcers/perforation (Figure 2), some form of systemic antacid (the author prefers a proton-pump inhibitor for 7 to 10 days) should be considered. Likewise, dogs with esophageal signs (regurgitation, drooling) in the postoperative period should be treated for esophageal motility dysfunction by adding some type of prokinetic agent (ie, cisapride) for the same duration. These agents will enhance gastric emptying and minimize the volume of fluid that may reflux into the esophagus.

Figure 2. This dog was treated for peritonitis after successful medical management of GDV 24 hours previously. A perforation of the stomach was discovered during an exploratory laparotomy.

ComplicationsIleus may be seen postoperatively and usually resolves following correction of the GDV. However, gastric perforation leading to peritonitis is always a concern and should be carefully monitored.

In GeneralRelative Cost

Emergency care/stabilization costs-Emergency call fees, fluid therapy, gastric decompression, narcotics/sedatives or short anesthetic agents, laboratory costs, confirmatory radiographs, oxygen therapy, ECG monitoring, 2 to 3 days of critical care, case management fees (doctors, technicians): $$$$$

Surgery-All of the above with the addition of more ECGs, preoperative medications, and postoperative sequelae (disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, pain management, and aspiration pneumonia): $$$$$

PrognosisAfter surgery, the prognosis is good with recent mortality rates of 16.2% and 26.8% being reported.<sup17, 18sup> Prognosis is worse if a partial gastrectomy, splenectomy, or both are necessary. Other mortality-related factors include hypotension, peritonitis, sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and an interval between occurrence and treatment exceeding 6 hours.

Elevation of urinary 11-dehydrothromboxane B2 (11-DTXB2) excretion in dogs occurs with GDV. An increased 11-DTXB2-to-creatinine ratio following surgery is related to an increased incidence of postoperative complications.19

Future ConsiderationsRisk factors identified by Glickman, et al, have been helpful in identifying high-risk patients that may benefit from a prophylactic gastropexy using either standard laparotomy techniques, laparoscopy, or laparoscopy-assisted techniques.20-22