Pharmacokinetics is the study of how the body affects a drug (ie, absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination). Pharmacokinetic studies provide insights into determination of appropriate dosages for dogs and cats. Having a basic understanding of pharmacokinetic parameters and how they can be affected by disease allows for critical evaluation of these studies (Table 1).

Pharmacokinetics of Absorption

A drug must be absorbed into systemic circulation to exert a systemic effect. The extent and timing of absorption is affected by the route of administration.

Intravenous (IV) bolus administration results in delivery of 100% of the drug into systemic circulation and therefore skips the absorptive phase.

Intramuscular (IM) absorption is generally greater than subcutaneous (SC) absorption but can vary with individual drugs; both routes can be affected by the patient’s status, including hydration.

Oral (PO) absorption is considered the most variable route and can be affected by drug (eg, solubility, permeability) and patient (eg, gastric fluid volume and pH, feeding status, GI pathology) characteristics.

With few exceptions, other routes of administration require an absorptive phase for efficacy. For example, a drug applied topically but intended to have a systemic effect (eg, transdermal) needs to be absorbed; however, a drug applied topically but intended to have a local effect (eg, otic formulation) does not need to be absorbed.

Maximum Concentration

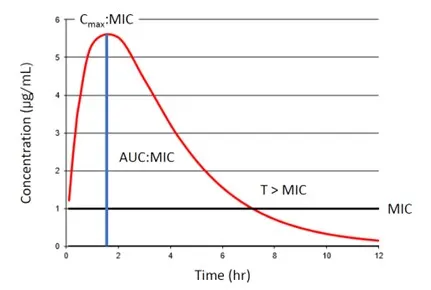

Cmax (ie, maximum concentration) refers to the highest concentration of a drug measured in plasma. For some drugs, this may relate to efficacy (Figure 1). For example, aminoglycoside antibiotics are administered to reach a Cmax 10 times higher than the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the bacterial infection being treated. Cmax is highest following IV administration and typically lowest and most variable following PO administration.

FIGURE 1 Schematic representation of the target pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions for certain antibiotic classes. Cmax:MIC of 8 to 10 times relates to efficacy for aminoglycoside antibiotics, AUC:MIC of 72 relates to efficacy of fluoroquinolone antibiotics, and T > MIC relates to efficacy of beta-lactam antibiotics.

Time to Maximum Concentration

Tmax (ie, time to maximum concentration) refers to the time taken to reach Cmax. Tmax is often prolonged with extended-release formulations administered extravascularly (EV), in which the absorptive phase is intentionally prolonged, and with transdermal formulations, in which the rate of absorption is affected by inherent drug characteristics and the surface area to which the drug is applied. Tmax can relate to how quickly a drug is able to reach maximum effect; shorter Tmax is preferred for emergent and life-threatening conditions. Following IV bolus administration, Tmax is almost immediate, making this route preferrable when immediate effects are desired. In addition, many drugs used for treatment of acute pain (eg, dexmedetomidine, methadone) have rapid Tmax following IM administration and thus have a quick analgesic effect.

Area Under the Curve

Area under the curve (AUC; in pharmacokinetics, the area under the concentration vs time curve) represents total exposure to a drug after administration. For many antibiotics, AUC is used to determine efficacy against specific bacteria (Figure 1). For example, the susceptibility criteria for fluoroquinolone antibiotics has been revised to be dose-dependent based on an AUC:MIC ratio of 72.1

Bioavailability

F (ie, bioavailability [expressed as a percentage]) refers to the percentage of a dose that is absorbed. For IV administration, F is 100%. Absolute bioavailability is calculated when an EV route is compared to an IV route [F = (AUCEV/AUCIV) × 100]; resulting extravascular absorption is ≤100%. Occasional reports of EV routes with F >100% are available; this may occur with extended-release formulations, in which the absorptive phase is longer than the elimination phase (ie, flip-flop kinetics), in drugs with significant oral transmucosal absorption (eg, buprenorphine), or with experimental artifacts or errors in study design.2-4 F can also be relative, in which an EV route is compared to a different EV route [F = (AUCEV1/AUCEV2) × 100] or when a formulation is compared to another formulation using the same route.

Bioequivalence

Bioequivalence is how the FDA evaluates generic drugs relative to the innovator drug. Two formulations are considered bioequivalent when the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of both Cmax and AUC are within 80% to 125% of each other.5 FDA-approved generic formulations of brand name drugs are bioequivalent in the species for which they are licensed. Compounded formulations are not FDA-approved, bioequivalence is rarely determined, and therapeutic failure may be attributable to decreased absorption.6,7

Carprofen provides an example of how pharmacokinetics and absorption can inform clinical practice. FDA-approved products for use in dogs can be administered SC and PO. SC administration results in a lower Cmax and longer Tmax; the onset of analgesia is thus delayed compared with PO administration.

Pharmacokinetics of Distribution

After absorption into systemic circulation, a drug must distribute to its site of action. For some drugs, the site is the plasma itself or the interstitial fluid of tissues. For other drugs, the site of action is intracellular or in protected sites (eg, CNS, eye, prostate). Lipophilic, un-ionized drugs with a small molecular weight and low protein binding distribute beyond the interstitial fluid more efficiently.

Volume of Distribution

Vd (ie, volume of distribution) refers to a theoretical volume of fluid into which a drug dissolves after absorption and is calculated as dose/Cmax. The calculation relies on plasma concentrations, which are affected by F and can therefore only be accurately represented using an IV administration dose.

Drugs with a very small Vd stay in the plasma and interstitial fluid. For example, monoclonal antibodies are very large molecules with a Vd of 0.05 L/kg and are confined to the plasma.8 NSAIDs are highly protein bound with a Vd of 0.2 to 0.3 L/kg and remain in the plasma and sites of inflammation.9 Opioids need to reach the CNS for primary analgesic effects and have very high distribution; fentanyl has a Vd of ≈5 L/kg in dogs.10

Interpretation of Vd is important for treatment of infection in a protected site, in which antimicrobials with a large Vd (>1 L/kg) are preferred.11 For example, enrofloxacin has the highest Vd among veterinary fluoroquinolones and is preferred for diseases like prostatitis.12 Patient factors can also affect Vd due to alterations in total body water content, particularly water-soluble drugs in neonates and dehydrated patients.

Pharmacokinetics of Metabolism & Elimination

Metabolism and elimination are distinct processes that are often grouped together because the general purpose of hepatic drug metabolism is to produce a more water-soluble metabolite ready for elimination via the kidneys. As such, these phases are often most affected by renal and/or hepatic disease.

Clearance

Cl (ie, clearance) refers to the volume of blood cleared of a substance per unit of time, has units of flow adjusted for body weight (mL/kg/minute), and is calculated as dose/AUC. The calculation relies on AUC, which determines F and can therefore only be accurately represented using an IV administration dose.

Most pharmacokinetic studies report total body Cl, which represents hepatic, renal, and other elimination routes without differentiation or accounting for the effect of being cleared by metabolism. In dogs, Cl values of 41, 17.4, and 5.8 mL/kg/minute are considered high, medium, and low, respectively; in cats, the corresponding values are 50, 22, and 7.3 mL/kg/minute.13 Drugs with high Cl disappear from the plasma rapidly and often have a shorter duration of effect; very high Cl rates may indicate a drug can only attain sustained therapeutic concentrations using a CRI (eg, fentanyl, dobutamine).

Elimination Half-Life

Elimination half-life (ie, T½) is the time needed to reduce the plasma drug concentration by 50%, is a secondary parameter calculated from Vd and Cl, and may change with alterations in either of those parameters. Half-life should not be used to determine an administration interval but is useful for determining accumulation of drugs with multiple administration regimens and time to steady-state plasma concentrations, which typically occur after 4 to 5 half-lives. Steady-state concentrations represent the time when drug input and output are similar with each successive dose and are correlated with the time to maximum effect. Drugs with long half-lives may require a loading dose to have a timely effect, as seen with potassium bromide.14

If IV administration is not possible, Vd and Cl are sometimes reported following EV administration, denoted as Vd/F or Cl/F. These values often overestimate the true values.

Conclusion

Pharmacokinetics may appear daunting, but general knowledge of the basis and interpretation of these parameters can help inform decision-making and drug choices. Understanding the influence of patient factors on drug pharmacokinetics (see Patient Characteristics That May Affect Drug Pharmacokinetics) may improve efficacy and decrease the risk for drug toxicity.

Patient Characteristics That May Affect Drug Pharmacokinetics

Drug transporter deficiencies

Increased drug distribution across barriers

Multidrug resistance gene (MDR1 gene, also known as ABCB1 gene) mutation (also known as ABCB1-1delta [dogs] or ABCB1 1930_1931del TC [cats]) results in P-glycoprotein deficiency in dogs and cats.

Example: Ivermectin- and eprinomectin-caused neurotoxicity

ABCG2 mutation in cats

Example: Enrofloxacin-caused retinal toxicity

Decreased biliary excretion

MDR1 gene mutation in dogs and cats

Example: Vincristine/vinblastine/vinorelbine leukotoxicity and GI toxicity

Drug metabolizing enzyme polymorphisms

Decreased drug metabolism and elimination

Decreased cytochrome (CYP) 2B11 enzyme expression

Example: Prolonged recovery from injectable anesthesia in greyhounds

GI disease

Decreased enteral drug absorption

Emesis, altered transit times, thickened intestinal walls

Example: Need for readministration of capromorelin in cats that vomit within 15 minutes of administration

Hepatic disease

Decreased drug metabolism and/or elimination

Significant hepatocellular dysfunction or cholestatic disease, causing decreased Cl

Example: Decreased cyclosporine Cl in dogs; decreased oral mirtazapine and ondansetron Cl (Cl/F) in cats

Renal disease

Decreased drug elimination

Significant renal impairment or outflow obstruction, resulting in decreased Cl

Example: Increased enalaprilat (but not benazeprilat) AUC in dogs; decreased oral mirtazapine and ondansetron Cl (Cl/F) in cats