Melody, a 6-year-old spayed 8.2-lb (3.7-kg) Maltese dog, was presented for polyuria, polydipsia, and hyporexia. She was previously diagnosed with meningoencephalitis of unknown origin, which has been treated with prednisone (2 mg/kg PO every 24 hours). Attempts to taper prednisone have resulted in relapse of neurologic disease.

Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed 1 month prior to current presentation; porcine lente insulin was prescribed starting at ≈0.3 units/kg SC every 12 hours and increased to 1.1 units/kg SC every 12 hours. The owner indicated Melody has had a history of a picky appetite and typically prefers to graze food throughout the day. She eats <50% of her normal meal 3 to 4 times per week, receiving half of the insulin dose when this occurs. She has had intermittent episodes of worsening hyporexia to anorexia and was anorectic on the day of presentation.

Physical Examination

Physical examination was largely unremarkable other than moderate muscle atrophy, a historical grade II/VI left apical heart murmur, mild periodontal disease, mild cranial abdominal organomegaly, and pain.

Differential Diagnoses

Differentials for persistent polyuria and polydipsia in this patient included secondary to systemic corticosteroids, periods of hyperglycemia as a result of inadequate management of diabetes mellitus, and/or comorbidity (eg, renal disease, hyperadrenocorticism). Based on a serum chemistry profile performed the month prior, the top differentials for history of a finicky appetite with episodes of hyporexia to anorexia included chronic enteropathy and chronic pancreatitis.

Diagnostics

Venous blood gas analysis and serum ketones (beta-hydroxybutyrate [BHB]) were measured to assess for ketoacidosis; results revealed ketosis (BHB, 1.6 mmol/L; reference interval, <0.6 mmol/L) without acidosis.1 A continuous glucose monitor (CGM) was placed to assess glycemic control and determine whether periods of hyperglycemia could explain polyuria and polydipsia. CBC and serum chemistry profile were submitted to evaluate for systemic inflammation, renal parameters, markers of GI health (eg, albumin, cholesterol), DGGR lipase, and liver enzymes. Serum cobalamin was performed to further assess for GI disease. DGGR lipase is the assay included on the serum chemistry profile run by the reference laboratory and has been shown to correlate with pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity.2 Urinalysis was submitted to evaluate for renal disease.

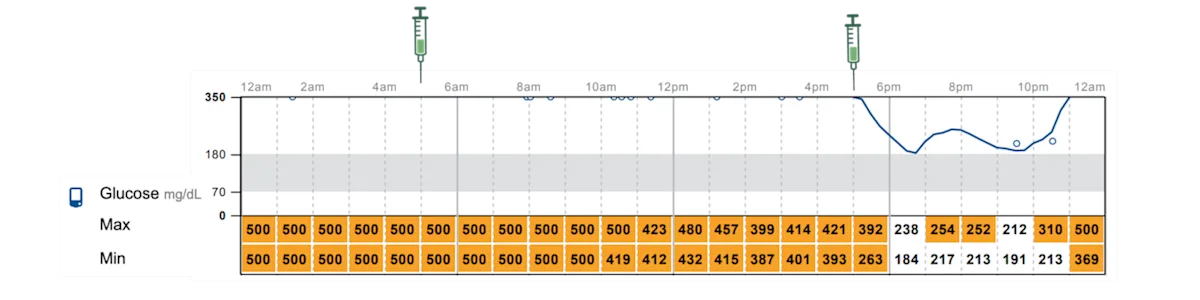

A blood glucose curve revealed hyperglycemia with interstitial glucose readings >400 mg/dL (reference interval, 68-104 mg/dL) for the majority of a 24 hour-period (Figure 1). Nadir was 184 mg/dL. Insulin duration of action was not clear because the patient’s poor appetite resulted in inconsistent caloric intake and variable insulin administration. Abnormalities observed on CBC and serum chemistry profile results included increased DGGR lipase measurement, mild hypoalbuminemia and high normal globulins, and an inflammatory leukogram (Table). These clinicopathologic abnormalities, combined with a history of acute inappetence and a longer history of waxing and waning appetite, were suggestive of acute-on-chronic pancreatitis.

FIGURE 1 CGM daily log showing glycemic control at initial assessment. Interstitial glucose concentration (mg/dL) is on the y-axis, and time (hours) is on the x-axis. Serial readings are noted by the line within the graph; exact values are shown in the columns below the x-axis. Porcine lente insulin was administered twice daily (at 5:00 AM and 5:00 PM), as indicated by the syringe icons.Highlighted numbers indicate readings above the target range; nonhighlighted numbers indicate readings within the target range.Created with BioRender. Prieto, J. (2025) BioRender.com/q1ol7j6

The owner was given the option to treat presumptively or pursue abdominal ultrasonography to further evaluate the pancreas. Abdominal ultrasonography was elected; results supported a diagnosis of acute-on-chronic pancreatitis, demonstrating a hypoechoic pancreas surrounded by hyperechoic mesentery.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic results suggested that persistent polyuria and polydipsia were most likely caused by inadequate control of diabetes mellitus. According to Project ALIVE (ie, Agreeing Language in Veterinary Endocrinology), insulin resistance describes the presence of varying degrees of interference of insulin action on target cells and is not defined by a specific threshold of exogenous insulin dose or by the change in blood glucose following insulin injection.3 Melody was believed to have corticosteroid-mediated insulin resistance as a result of the previously administered prednisone. Exogenous corticosteroids may impair glucose metabolism, increasing insulin requirements and inflammation associated with pancreatitis, which can subsequently increase counterregulatory hormones (eg, cortisol, catecholamines).4

Diagnosis: Corticosteroid-Mediated Insulin Resistance Complicated With Acute-on-Chronic Pancreatitis

Treatment & Long-Term Management

Pancreatitis was treated on an outpatient basis with maropitant for nausea and gabapentin for pain; food was transitioned to an ultra-low–fat diet. Insulin was transitioned to degludec insulin (starting dose, 4 units (1.1 units/kg) every 24 hours) to allow Melody to graze food throughout the day. A CGM was placed to monitor glycemic control.

Outcome

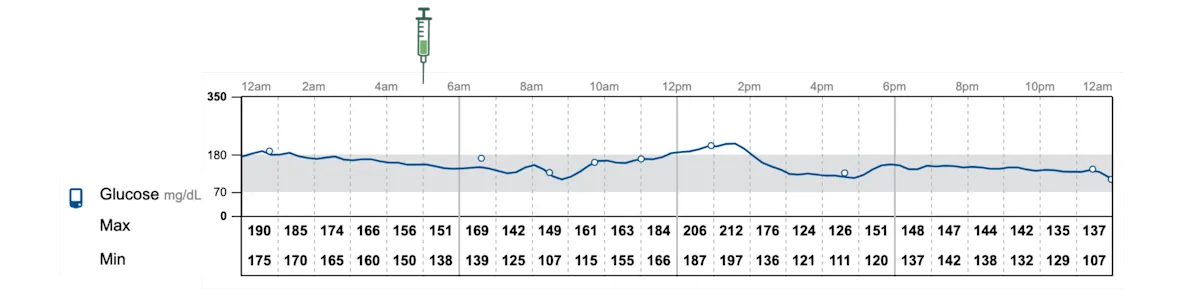

Pancreatitis resolved, and insulin was titrated up to 5 units (1.3 units/kg) every 24 hours based on interstitial blood glucose readings. Interstitial glucose concentrations measured with a CGM following determination of the final dose of insulin ranged from ≈100 to 200 mg/dL over a 24-hour period (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 CGM daily log showing glycemic control after treatment for pancreatitis and changing insulin types. Interstitial glucose concentration (mg/dL) is on the y-axis, and time (hours) is on the x-axis. Serial readings are noted by the line within the graph; exact values are shown in the columns below the x-axis. Degludec insulin was administered once daily (at 5:00 AM), as indicated by the syringe icon. Created with BioRender.Prieto, J. (2025) BioRender.com/q1ol7j6

Discussion

A poorly regulated diabetic patient will have clinical signs consistent with hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia or will require frequent increases or decreases in the insulin dose.

Monitoring

When evaluating a diabetic patient with signs consistent with hyperglycemia (eg, polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, weight loss), glycemic control should be evaluated with an 8- to 12-hour blood glucose curve or ≥1 days with a CGM.5 This evaluation allows determination of the time a patient is hyperglycemic, duration of action of insulin, and peak activity of insulin (ie, interstitial glucose nadir) timing.6 A particular flash glucose monitoring system has been robustly described for use in veterinary medicine.7-11 CGMs allow evaluation of glycemic control in the home, with normal dietary and activity habits of the patient. CGMs can measure glucose for up to 14 days, allowing assessment of intra- and interday variability.12 The most significant disadvantage of a CGM is premature device detachment and, in some cases, increased pet owner anxiety caused by observing glucose readings that they may perceive as suboptimal.13

Insulin

When episodes of hypoglycemia (glucose, <60-65 mg/dL) are observed, the insulin dose should be reduced by as much as 50%, especially in patients with clinical signs of hypoglycemia.5 Insulin types may need to be switched if the duration of action is too long or short. For example, in a dog receiving neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) and with an interstitial glucose nadir of 100 mg/dL 2 hours postinjection, transition to a longer-acting insulin (eg, porcine lente insulin) should be considered.5,6

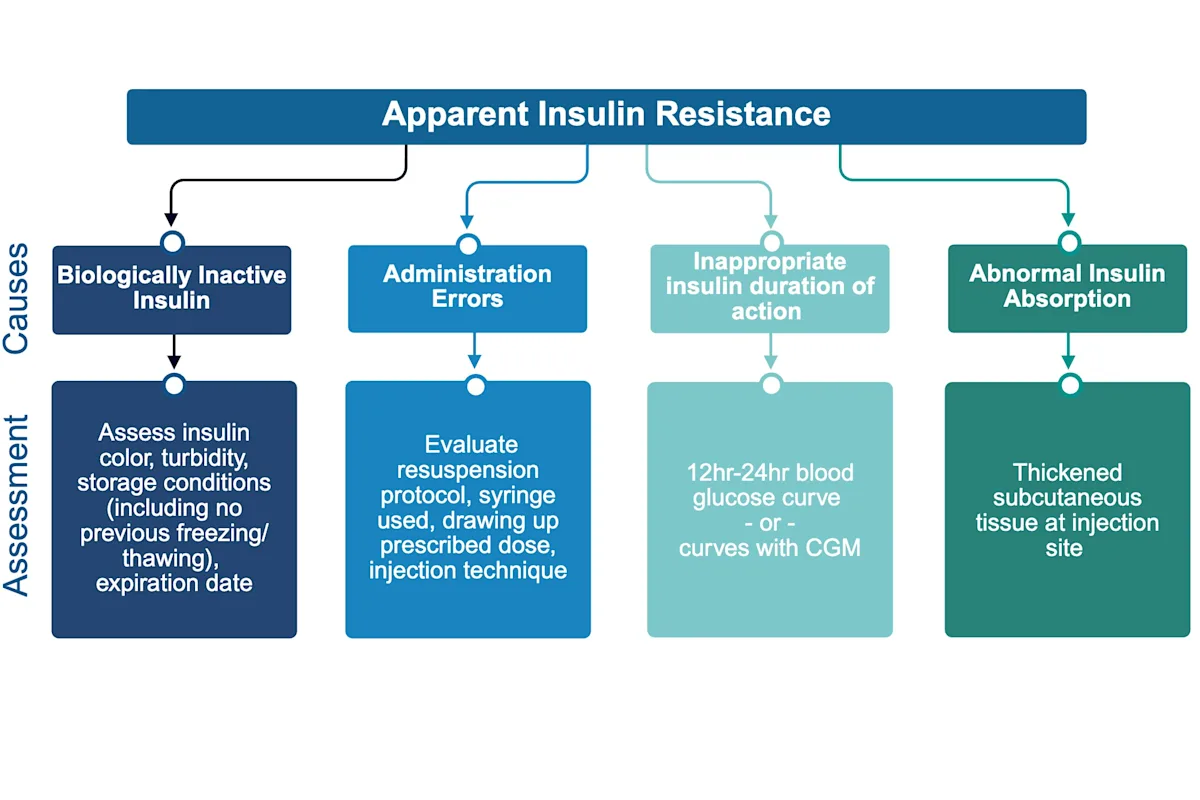

For cases in which insulin has been titrated to 1 to 1.5 units/kg/dose and significant hyperglycemia persists (interstitial glucose nadir, >150 mg/dL, or glucose, >300 mg/dL), the patient should be assessed for apparent or true insulin resistance.5,6 Causes of apparent insulin resistance (Figure 3), including administration of a biologically inactive insulin and administration errors, can be ruled out by replacing insulins used longer than the manufacturer’s recommendations and, if feasible, asking the owner to bring their insulin administration supplies to the clinic to demonstrate their injection technique.5,6 In some cases, skin and subcutaneous tissue in the area where insulin is given become thickened, impairing insulin absorption; rotating insulin injection spots around the intrascapular region can help prevent this phenomenon.6

FIGURE 3 Assessment of causes of apparent insulin resistance.5,6Created with BioRender. Prieto, J. (2025) BioRender.com/q1ol7j6

Diabetes management is complex, and the number of available veterinary insulins makes selection difficult. This case-based quiz can help guide the best choices for your patients.

Insulin Resistance

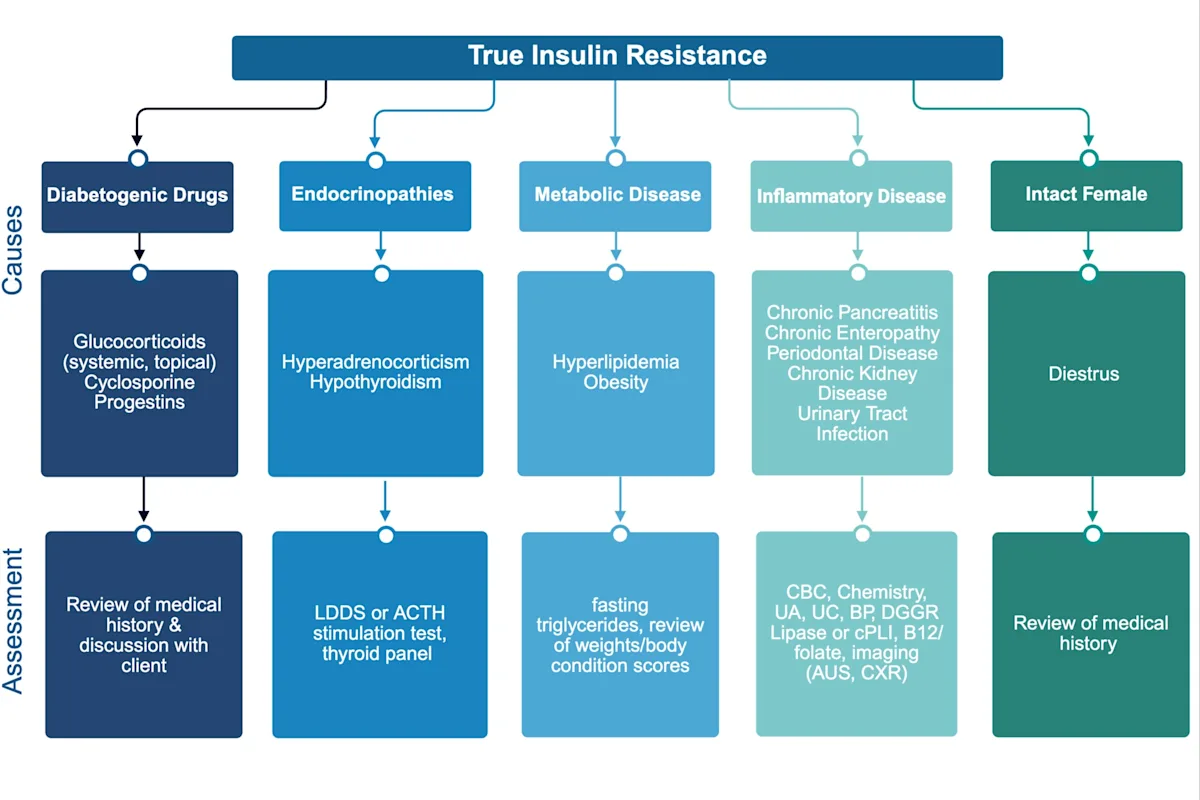

In patients with true insulin resistance, insulin produces a subnormal biologic effect due to impaired insulin binding to its receptor or receptor function.6 Emphasis has historically been placed on exceeding a specific dose of exogenous insulin in diagnosis of insulin resistance; however, there is biological variability in insulin requirements between and within individual patients.14 Lifestyle factors (eg, diet, activity level, sleep patterns) can also impact insulin requirements.15 Common causes of insulin resistance in dogs include treatment with diabetogenic drugs, endocrinopathies, metabolic diseases, inflammatory diseases, UTIs, and diestrus in intact females (Figure 4).5,6

FIGURE 4 Assessment of causes of true insulin resistance.5,6Created with BioRender. Prieto, J. (2025) BioRender.com/q1ol7j6

AUS, abdominal ultrasonography; B12, cobalamin; BP, blood pressure; cPLI, canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity; CXR, chest (thoracic) radiography; LDDS, low-dose dexamethasone suppression; UA, urinalysis; UC, urine culture

Investigation

Assessment for suspected insulin resistance should include reviewing the patient history for diabetogenic drug administration and performing a thorough physical examination to look for clinical signs of a comorbidity (with oral examination to assess for periodontal disease).5,6 Baseline diagnostics include CBC, serum chemistry profile, urinalysis, blood pressure measurement, and serum triglyceride measurement. Thyroid and adrenal testing (eg, thyroid panel, ACTH stimulation, low-dose dexamethasone suppression) should also be considered, especially if the initial diabetes mellitus diagnosis was >1 month ago.5,6 Additional diagnostics (eg, vitamin B12/folate testing, canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity, thoracic radiography, abdominal ultrasonography) may be indicated pending examination and initial assessment results.5,6

Management

Treatment of an identified comorbidity can improve management of diabetes mellitus and associated clinical signs. Ovariohysterectomy is indicated in intact female dogs.5 The time frame for treating the comorbidity dictates adjustments in the insulin dose.5,6 For example, weight loss in an obese dog can take months, so the insulin dose should be increased initially along with feeding a diet ideal for weight loss to achieve better glycemic control.6 In contrast, hypothyroidism treatment is expected to normalize total thyroxine in 2 to 4 weeks, likely necessitating a decrease in the insulin dose once the euthyroid state has been achieved.6 Increased glucose monitoring should be instituted during the period in which changes in insulin requirements are expected so insulin requirements can be adjusted as needed to prevent hypoglycemic episodes while controlling clinical signs of diabetes.

For patients with diabetes that is difficult to control, finicky appetites, and/or intra- or interday variability in glycemic control, basal insulins (eg, degludec, U300 glargine) can be advantageous.14 Basal insulins have a constant duration of action (peakless) and do not require administration timed with a meal.14 Degludec insulin has a duration of action of >20 hours in healthy dogs.16 A recent study demonstrated that 84% of diabetic dogs treated with degludec insulin only required once-daily administration.17 Importantly, due to the long duration of action, glycemic control with degludec insulin should be assessed with a CGM.14

The starting dose of degludec insulin for a dog newly diagnosed with diabetes is 0.5 units/kg once daily.17 When transitioning from NPH or a porcine lente insulin, the same dose is recommended. For example, if a patient is receiving porcine lente insulin at 5 units every 12 hours, degludec insulin could be started at 5 units every 24 hours.17

Treatment at a Glance

The insulin dose should be decreased if hypoglycemic episodes are suspected or documented.

Transition to a different insulin is warranted if the current insulin duration of action is suboptimal.

Owner insulin preparation and administration protocols should be observed if possible.

Diabetogenic drugs should be discontinued or the dose reduced as much as possible.

Comorbidities that impact insulin requirements should be screened for and treated if identified.

Rapid Dose Titration Protocol

A study described a rapid dose titration protocol using a CGM that involved increasing the degludec insulin dose by 10% to 30% (or 1 unit for dogs weighing <17.6 lb [8 kg]) every 1 to 3 days as long as the interstitial glucose nadir was >350 g/dL.17 In cases in which the interstitial glucose nadir was <350 mg/dL, interstitial glucose readings were monitored for an additional 2 to 3 days or until a consistent pattern was observed (meaning the time and magnitude of interstitial glucose nadirs and postprandial peaks over 24 hours were similar to the previous 24 hours).17 The decision to transition from administration every 24 hours to every 12 hours was recommended when the interstitial glucose nadir was <150 mg/dL and interstitial glucose measurements were >300 mg/dL for >12 hours during each 24-hour period.17 In some cases, lifestyle changes (eg, time of administration, exercise, diet) could also be adjusted before transitioning to administration every 12 hours. When transitioning from administration every 24 hours to every 12 hours, the degludec insulin dose was decreased by 30% per injection, and the first new dose was administered 12 hours after the last every 24 hour injection.17 In cases in which there was a consistent pattern of postprandial hyperglycemia and persistent clinical signs, a basal–bolus protocol (ie, combination of a basal insulin [eg, insulin degludec] and a bolus insulin [intermediate-acting insulin] administered at meals) can be considered with the addition of an intermediate-acting insulin or a 70/30 NPH/regular insulin mix.14,17

The rapid dose titration protocol involves close communication between clinicians and owners. Dose adjustment recommendations were based on interstitial glucose readings in combination with daily updates from the owner regarding dose and timing of insulin injections, feeding times, amount and type of diet, timing of exercise, changes in behavior, changes in urination or thirst, clinical hypoglycemic episodes, and any stressors.17

How to Avoid Overwhelming Pet Owners With Information

Owners bringing sick pets to the clinic may already feel overwhelmed. Avoid inundating owners with information and help them retain key concepts with these tips.

Prepare the owner by letting them know you are about to share a lot of information.

Split information into chunks, and be strategic about what is shared when.

At the first appointment, only share information that is critical. Save noncritical information for future conversations.

Use handouts, and empathize with the owner about the amount of information to be shared.

Reading the handout to the owner and highlighting important information can be helpful.

Provide links to helpful videos.

For more on helping education stick, check out this article on Avoiding Overwhelming Clients With Information.

Conclusion

Melody could be classified as a poorly regulated diabetic patient in multiple ways. Her insulin dose had to be frequently changed due to her decreased appetite and resistance to being meal fed. She had iatrogenic insulin resistance, with exogenous corticosteroid treatment and presumptive pancreatitis resulting in clinical signs associated with resulting hyperglycemia (persistent polyuria and polydipsia—albeit complicated by treatment with corticosteroids). Although the corticosteroids could not be discontinued, adjusting to an ultra-low–fat diet may have ameliorated suspected chronic pancreatitis. Transitioning to degludec insulin allowed for consistent insulin treatment with less day-to-day variability in glycemic control.

Take-Home Messages

Patients with poorly regulated diabetes have clinical signs of hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, or insulin resistance or require frequent insulin dose adjustments.

Blood glucose curves are needed to identify hypoglycemia, assess insulin duration and dose, and address suspicion for apparent or true insulin resistance.

Apparent insulin resistance may be due to use of a biologically inactive insulin, administration errors, suboptimal insulin duration, or thickened tissue at the injection site.

Causes of true insulin resistance include diabetogenic drugs, endocrinopathies, metabolic diseases, inflammatory diseases, UTIs, and diestrus in intact female dogs.

Basal insulins (eg, degludec) can help regulate patients with picky appetites and glycemic variability.