The Case: Disastrous At-Home Fracture Stabilization

Clinical History

A 10-year-old intact male collie had been hit by a car. The treating veterinarian diagnosed fractures of the left tibia and fibula and recommended surgical repair. The client declined surgical treatment due to cost and elected conservative treatment consisting of splint application and weekly clinic visits to monitor healing and change/adjust the splint. After initial treatment, the client did not follow up at the clinic as instructed, and changed the splint at home. Upon return to the clinic 4 weeks later, the client reported that skin wounds and swelling of the limb had occurred “quite a while ago” and persisted. The patient had been exhibiting non-weight–bearing lameness of the left hind limb even with the splint in place.

Physical Examination

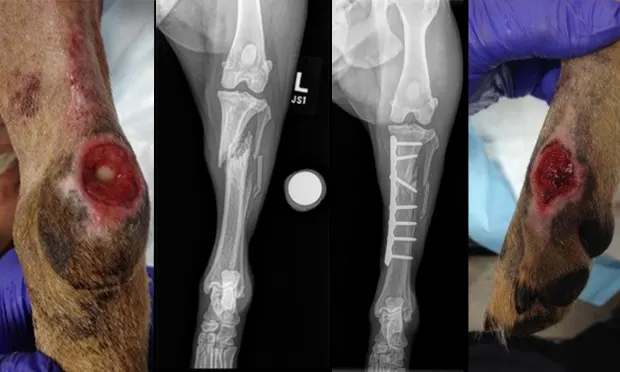

Image 1. Lateral metatarsal skin lesion; Image 2. Caudal/plantar hock lesion.

Patient was sedated for examination (hydromorphone, 0.1 mg/kg and dexmedetomidine 10 mcg/kg IM).

Firm, focal swelling of proximal left tibia

Lateral instability of the tibia when manipulated

Soft tissue wounds (some full thickness) of left tarsus/metatarsus/hock: likely pressure sores (Images 1 and 2)

Ambulatory x3; non-weight–bearing lameness of left hind limb. Remainder of examination was within normal limits. Referral for surgical consultation and surgical repair of nonhealing fractures was recommended; client accepted referral.

Diagnostics

Image 3: Preoperative craniocaudal radiograph.

Left tibial/fibular radiographs (at time of surgical consultation; Image 3)

Comminuted, oblique fracture of the proximal diaphysis of the left tibia with minimal callus formation

Comminuted, multiple fractures of the mid diaphysis of the left fibula with minimal callus formation

Presurgical CBC/serum chemistry panel: Within normal limits

Aerobic culture of soft tissue wounds: Moderate growth of Enterobacter spp and Pseudomonas spp

Initial Therapy

Skin wounds were clipped and cleaned; Curasalt (sodium impregnated) bandages were applied over the wounds prior to soft padded bandage and splint placement on the plantarolateral aspect of the left hind limb from distal phalanx to mid femur.

Cephalexin (30 mg/kg q8h PO) initiated prior to surgical treatment.

Surgical Treatment

Tibial fracture repaired with a contoured bone plate. Significant scar tissue and bony callus were debrided prior to placement of the plate.

Postoperative Management

A splint and bandage were placed postoperatively and changed 5 days later.

Medications dispensed:

Tramadol (2 mg/kg q8h PO)

Meloxicam (0.1 mg/kg q24h PO)

Cephalexin (30 mg/kg q8h PO) – empiric treatment pending culture and sensitivity results

Marbofloxacin (4 mg/kg q24h PO) – Initiated 4 days postop based on culture and sensitivity (C/S) results

Strict cage rest and exercise restrictions strongly recommended

Follow-up

Weekly bandage changes until soft tissue wounds were resolved

Progress exam with radiographs at 4 and 8 weeks after surgery

No complications occurred in the postoperative period

Clinical Outcome

Image 4. Craniocaudal view 8 weeks after surgery.

Skin wounds healed completely without further complications

Tibial fracture almost completely healed 8 weeks after surgery (Image 4).

Fibular fracture healed after additional 4 weeks of exercise restriction

The Generalist’s Opinion

Barak Benaryeh, DVM, DABVP

This dog clearly received the attention required but not until things went wrong. The level of care given on the second presentation, including bone plating, was at a specialty level and well beyond the scope of most general practitioners. My focus is to examine whether the initial complication could have been avoided. When is it best to refer a fracture and when is it appropriate to keep a case in house? Factors to consider in the decision include mechanical, biologic, and clinical.

Mechanical Factors

Mechanical factors refer specifically to the fracture type. We were not provided radiographs from the initial presentation but we do have the presurgical films. This fracture was oblique and at the proximal diaphysis of the tibia and fibula. The bone pieces were approximately 50% displaced with possible additional smaller fragments. The forces to consider in fracture stabilization are axial (compression and tension), bending, rotation, and shear. Very little, if any, bone stability remains in this fracture. If it could be nonsurgically reduced, the oblique nature of the fracture would help to counteract rotational and some bending forces, but there is nothing to counteract any axial or shear forces: that would be the job of a splint or cast. External devices provide some support but significant micromotion within the fracture would remain. Thus, such repair is at high risk for failure. Lastly, the location of the fracture was working against resolution in that proximal tibial fractures are at a higher risk for delayed unions and nonunions.1

Biologic Factors

Biologic factors are mainly the patient’s age and state of health. This dog had no underlying diseases but was 10 years old. Increasing age in dogs correlates with slower fracture healing times.2 This is an important consideration when deciding the type of repair needed.

Clinical Factors

Clinical factors include the financial constraints of the owners, level of client compliance, and level of comfort, expertise, and willingness on the part of the veterinarian. These clients declined surgery at first due to financial constraints but were able to afford what ended up being a more expensive treatment in the end. Is it possible that had they been made truly aware of the risks, they would have decided differently? In addition, they were clearly very poorly compliant, as they did not return for follow-up and chose instead to change the splint themselves. There may have been no way to foresee their actions, but the more we target our discussion, the better we will be at avoiding situations such as these. It’s also important to follow up with phone calls, especially if a client fails to show up for a recheck. Nearly all veterinary software programs have a function for phone call reminders. These can be delegated to the staff on a daily basis and noncompliant clients can be reminded of the need for their follow-up visits.

In hindsight, it’s clear that these clients and the patient would have been best served by a referral. This patient’s age, type of fracture, and type of client all made for a perfect recipe for disaster. There is no telling if a stronger recommendation for a referral or a refusal to treat on the part of the veterinarian would have made any difference. There is also no telling whether more appropriate follow-up would have resulted in a better outcome. Sometimes in our profession we are stuck between a rock and a hard place. The best we can do is try to establish basic guidelines about which fractures we should and should not attempt to treat.

Barak Benaryeh, DVM, DABVP, is the owner of Spicewood Springs Animal Hospital. He graduated from University of California–Davis School of Veterinary Medicine in 1997 and completed an internship in Small Animal Medicine, Surgery, and Emergency at University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Benaryeh has also taught practical coursework to first-year veterinary students and was a primary veterinary surgeon for the Helping Hands Program, which trains assistance monkeys for quadriplegic people. Dr. Benaryeh is certified by the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners in Canine and Feline Practice.

The Specialist’s Opinion

Jennifer L. Wardlaw, DVM, MS, DACVS–SA

Unfortunately the scenario described here is common: An owner chooses splints or bandages rather than the recommended surgery. Then, the ultimate treatment ends up costing more than the surgery would have if performed at the original presentation.

The Facts of the Case

The short oblique proximal tibial fracture in this case has shearing, compression, rotation, and distracting forces at play. It also involves a 10-year-old medium-large breed dog. Furthermore, even if the fibula had been intact as an internal splint, this fracture would have required a cast applied to the joint from above and below (ie, the stifle and hock). Without tibial stabilization, the fracture does not have any chance of forming a bony union: The thigh in most dogs is a widening triangle proceeding proximally, making it very difficult to keep a bandage and splint tight and in place. The conformation makes these fractures, in particular, extremely difficult to manage successfully without surgery. If the fibula had been intact, it would have counteracted much of the fracture forces and healing union may have occurred, as long as proper splinting and cage rest had been followed. If the dog was allowed to be too active, it is likely the fibula too would have fractured in short order. Thus, the nature of the fracture, the conformation of the dog, the age of the dog, and the eventual cost of splint material and follow-up visits combine to clearly make surgery the best option.

The Possibility of Union

Radiographs taken when the owner agreed to surgery show nice sharp edges and healthy bone; there is no evidence at all of callus 4 weeks after the initial presentation. I would call this delayed union, since at 4 weeks we would not expect union to have occurred. But this is not a nonunion, as that term implies a fracture that no longer shows any active, healing attempts and the bone edges would be rounding off. Nonunion fractures have a much worse prognosis and are further divided into viable and nonviable. These types of fractures need extra care with debridement to achieve healthy, bleeding bone ends, and bone grafts. In this case, the owners took action quickly after the initial delay and we simply have a delay in healing.

Skin Sores

Splint and casting sores are one of the major concerns with long-term management of fractures. Good sedation, as was used in this case, is needed for every bandage change. If the animal moves during the change, all the healing that was achieved in the last interval will be lost. While this did not evolve into an open fracture, the hock wound did proceed to expose bone. Once open sores are present, bandage changes must be performed much more frequently, resulting in more cost and inconvenience to the owner. The good news is that, even in the face of infection, a stable fracture will heal. If this had become an open fracture, the owner would likely have faced the necessity of paying for the bone plate to be removed once the fracture had healed to clear the final remains of infection. Bacteria form a protective glycocalyx on implants that prevents complete resolution of infection. The possibility of infection is another reason why Elizabethan collars are used to prevent incisional licking, and why bandages and splint need to be cared for so meticulously.

Communication

The major overall issue with this case was communication. The owner’s lack of follow-through caused this dog unnecessary pain and time for healing. Explaining weekly or more-frequent bandage changes with sedation and monthly radiographs and the high cost of this approach along with the poor chance of success will convince most owners to opt for surgery. I would have placed a splint––from past the toes to as far up the femur as possible––only if the owner had given me the choice between either splinting or euthanasia. Then, knowing the poor chance of success, follow-up with phone calls and education would become paramount.

Jennifer Wardlaw, DVM, MS, DACVS–SA, is a concierge board-certified veterinary surgeon at Gateway Veterinary Surgery in the St. Louis area. She continues as adjunct faculty at Mississippi State, as well as lecturing locally and nationally throughout the year at CVC, NAVC, AAHA, and local conferences. Dr. Wardlaw completed her veterinary degree at University of Missouri in 2004. She completed a rotating small animal internship, master’s degree, and Small Animal Surgical Residency at Mississippi State, where she won the American Veterinary Clinician’s Award while on faculty for 10 years.