Anal Sacculectomy in Cats

Perhaps because it is uncommon, misdiagnosed, or not reported, anal sac disease is not well documented in cats. Cats can have anal sac impaction, infection, abscessation, or neoplasia, any of which can result in discomfort or fecal obstruction. Closed anal sacculectomy is recommended to treat neoplasia or other conditions where wider margins may be necessary to remove all affected tissues or local contamination is a concern.

Related Article: Anal Sacculectomy

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs of feline anal sac disease include tenesmus, dyschezia, change in stool volume or consistency, perineal swelling or discomfort, scooting, recurrent constipation, abnormal tail carriage, ulceration, or draining tracts. Clinical signs can be confused with urinary tract problems or other constipation issues and may be missed by clients if signs are intermittent. In some cats with anal sac adenocarcinoma, the only sign is a palpable mass.1,2 Although anal sac disease can present at any age, neoplasia is most common in geriatric cats; in one report of 64 cats with anal sac adenocarcinoma, the median age was 12 years (range, 6–17 years).1

Diagnostic Findings

In cats with anal sac disease, diagnostics should start with a digital rectal examination. Because this procedure may be uncomfortable in patients with a small anus, appropriate restraint may require sedation or anesthesia. Full serum chemistry profile is recommended on presentation, as many cats with anal sac adenocarcinoma are geriatric and may have comorbidities. Unlike dogs, hypercalcemia is uncommon in cats with anal sac adenocarcinoma.1,2 If neoplasia is suspected, thoracic and abdominal radiography and abdominal ultrasonography should be requested to screen for metastatic disease in the lungs, liver, abdomen, and lymph nodes. Metastases have been suspected but have not been consistently confirmed in some cats with anal sac adenocarcinomas; true metastatic rate is unknown.1,2

Related Article: Anal Sacculectomy

If a mass is detected on digital rectal examination, samples obtained by fine-needle aspiration should be submitted for cytologic evaluation. Normal anal sac secretions in cats vary from light yellow–white or orange to tan or brown. The consistency may be thick and creamy or watery with inspissated material.3 Secretions in cats younger than 1 year of age are often watery. Microscopically, normal secretions contain large amounts of amorphous, basophilic material.3 Epithelial cells can be nucleated or nonnucleated with a mixed population of bacteria, predominantly gram-positive cocci. Healthy secretions may also have some neutrophils, monocytes, and yeast. Intracellular bacteria and erythrocytes are seldom identified in normal secretions.3

Cytology of inflamed anal sacs has not been described in cats; in a study comparing dogs with and without anal sac disease, there were no significant differences in numbers of bacteria or inflammatory cells.4 Cytologic appearance of anal sac adenocarcinoma can include clusters of papillary-shaped cells with poorly defined margins and malignant features (eg, nuclear or cellular pleomorphism, large nuclei, cytoplasmic vacuolization).5 Biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis; excisional biopsy is recommended to lower risks for complications (eg, draining tract formation).

Anatomy

Blood supply is provided by branches of the caudal rectal artery and vein. Anal sacs are surrounded by the external anal sphincter muscle and perineal fat and are positioned lateral to the duct openings, which are located on pyramidal prominences of the skin at 120° and 240° (ie, 4 and 8 o’clock) lateral to the mucocutaneous junction. The locations of the caudal rectal nerves have not been well documented in cats.

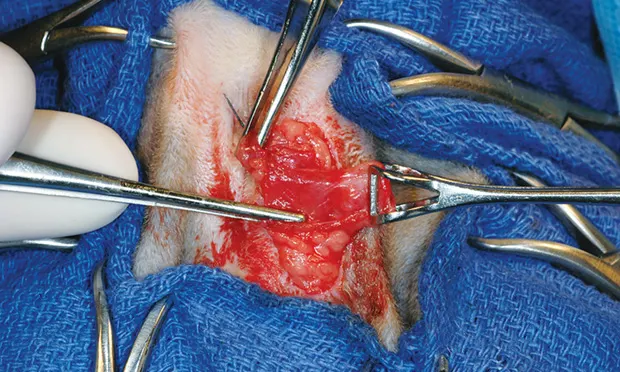

Anal Sacculectomy

Surgical preparation includes clipping the perineal region and tail base. Analgesia can be provided preemptively with epidural administration of morphine (0.1 mg/kg) combined with saline to make 1-mL volume. The anal sacs should not be expressed if neoplasia is suspected. For patients with anal sacculitis, the sacs can be expressed and flushed, although this may be difficult because of small duct size. Because bacteria are present, prophylactic antibiotic therapy (eg, cefazolin) is recommended.

Anal sacculectomy is performed with the cat in perineal position and the tail pulled forward. The table edge should be padded to avoid femoral region compression. To reduce pressure on the diaphragm, the thorax can be elevated by placing a rolled towel behind the elbows; ventilation should be assisted intraoperatively.

Postoperative Care

After surgery, an Elizabethan collar should be applied for 1 to 2 weeks, and standard litter should be replaced with pelleted paper to prevent local contamination during healing. Analgesia can be provided via injectable or oral buprenorphine or an NSAID (eg, robenacoxib at 1 mg/kg PO q24h for up to 6 days). The safety margin of robenacoxib has only been evaluated in young, healthy cats6; therefore, as with other NSAIDs, caution is necessary with robenacoxib use in cats with compromised renal or hepatic function.

Complications include hemorrhage, swelling, infection, dehiscence, persistence of clinical signs, anal deformation or stricture, incontinence, or mass recurrence.1,2 Long-term complications include fecal incontinence, draining tract or fistula formation, or anal strictures.1,2,7 Although these complications are uncommon, rate of occurrence likely depends on surgeon skill and condition severity. In one study of cats with anal gland adenocarcinomas, median survival time was 3 months (range, 0–23 months). In those cats, death or euthanasia resulted from primary disease, presumptive metastasis, recurrence, or perceived poor outcome.1,2

ELIZA RUFFNER, DVM, practices general medicine at Pine Valley Animal Hospital in Wilmington, North Carolina. Her interests include surgery, endocrinology, and ophthalmology. Dr. Ruffner earned her DVM from University of Tennessee.

MELISSA DANIELS FRANCHER, DVM, is a small animal practitioner in the Nashville area. Her foci are pain management, preventive care, ophthalmology, and internal medicine. Dr. Daniels earned her DVM from University of Tennessee.

COURTNEY SHERMAN, DVM, practices in Knoxville, Tennessee. Her interests are bovine reproduction and equine preventive medicine. She earned her DVM from University of Tennessee.

LAUREN OWENS, DVM, is completing an equine internship at Surgi-Care Center for Horses in Brandon, Florida and hopes to pursue a residency in equine surgery. Dr. Owens earned her DVM from University of Tennessee.

KAREN M. TOBIAS, DVM, MS, DACVS, is professor of small animal soft tissue surgery at University of Tennessee and mentors veterinarians in writing educational articles. She taught at University of Georgia and Washington State University, authored Manual of Small Animal Soft Tissue Surgery, and was coeditor of Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal. She completed her internship and residency at Purdue University and The Ohio State University, respectively, and earned her DVM from University of Illinois. Dr. Tobias presented on essential wound care techniques at the NAVC Conference 2013.