Diagnostic Imaging of Urinary Tract Calculi

Daniel VanderHart, DVM, DACVR

Urinary tract calculi are well documented in companion animals, and diagnostic imaging is important for detection. Radiography has long been the mainstay for detection of mineral opaque urinary calculi, but ultrasonography has gained in usefulness for both detection and better tissue characterization of the disease.1,2

Positive and negative contrast studies can provide additional, often valuable, information to aid in diagnostic evaluation of the urinary tract.

Nephrolithiasis & Ureterolithiasis

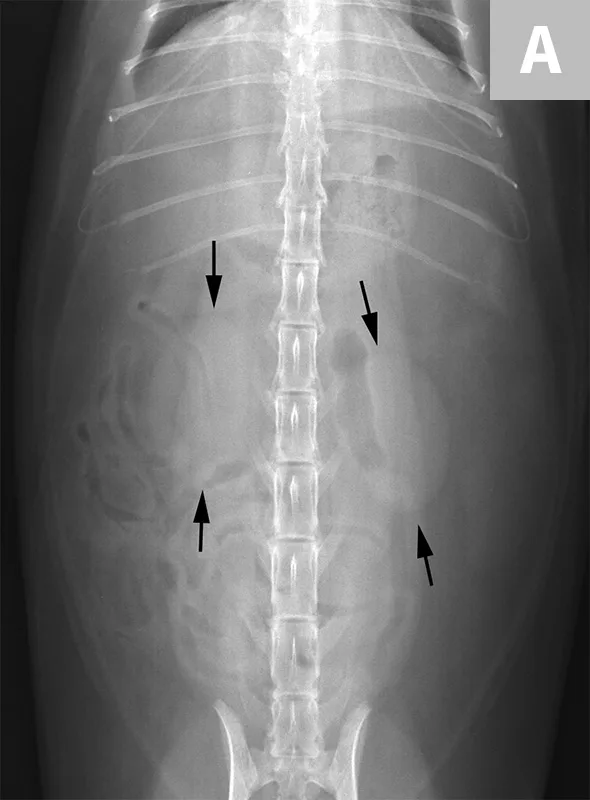

Identification of the normal appearance of the kidney on radiography and ultrasonography is critical prior to evaluation for abnormalities (Figure 1). In addition, several potential artifacts—or “pitfalls”—must be taken into account when radiographically or ultrasonographically evaluating the upper urinary system in dogs and cats (Figure 2).

Figure 1A Ventrodorsal radiograph of a normal cat for evaluation of the kidneys (arrows). Note the bean-shaped appearance, smooth capsular margin, normal size (approximately 2.2× the length of L2) and location. Both kidneys are more readily seen in this cat due to the amount of retroperitoneal fat. In the dog, the left kidney is easier to identify and evaluate routinely than the right, as the cranial pole of the right kidney border effaces with the renal fossa of the caudate lobe of the liver.

Figure 2A A right lateral radiograph of a normal dog. Notice several circular soft tissue opacities superimposed over the retroperitoneal space. These represent end-on vessels with renal veins seen cranially (arrow) and deep circumflex iliac vessels seen caudally (arrowheads).

Calculi within the kidney or ureter present diagnostic and management challenges. It is important to recognize renal calculi and differentiate them from dystrophic mineralization of the renal diverticula. While both dystrophic mineralization and calculi can be incidental findings, the presence of calculi can result in further complications. Calculi can obstruct the renal pelvis or ureter, predispose to pyelonephritis, or result in compressive injury of the renal parenchyma leading to progressive chronic kidney disease.3

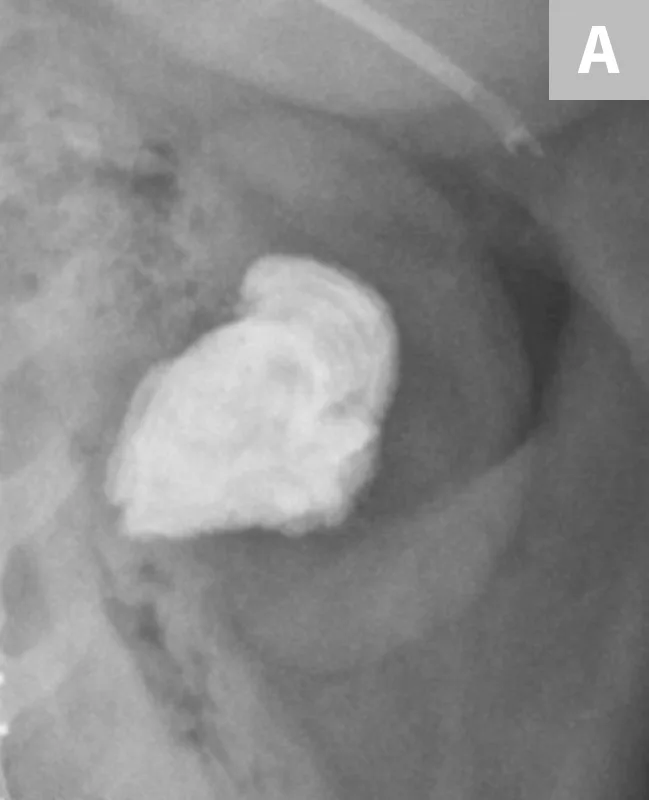

Renal calculi can vary markedly in size, number, shape, and opacity (Figure 3). Dystrophic mineralization of the renal parenchyma, often associated with the collecting system, is another differential for mineralization localized to the kidney (Figure 4). A combination of radiography, positive contrast radiography (excretory urography), and ultrasonography has been shown to have an increased sensitivity for the diagnosis of ureteral calculi when compared with ultrasonography alone (Figure 5).4

Figure 3A Close-up radiograph of the left kidney with a large, smoothly margined renal calculus in a clinically normal canine patient.

Figure 4A Close-up radiograph of the left kidney in a dog with well-defined, linear regions of mineralization localized to renal diverticula.

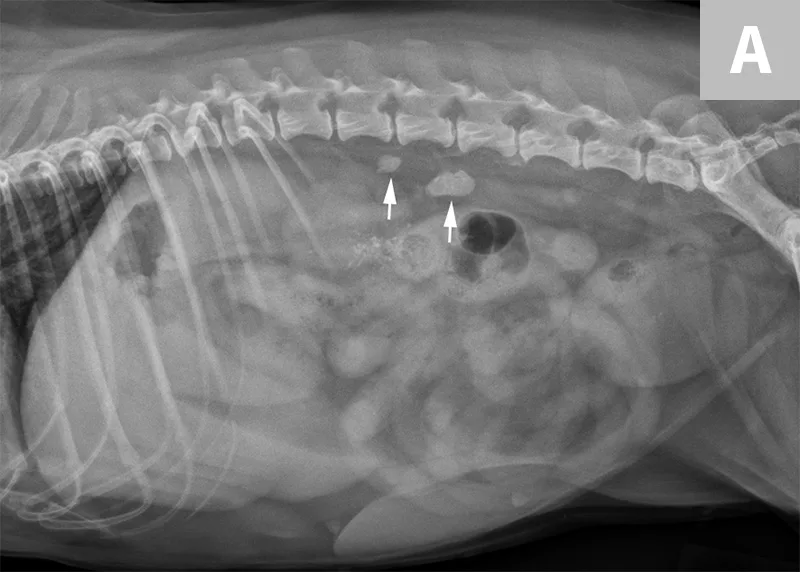

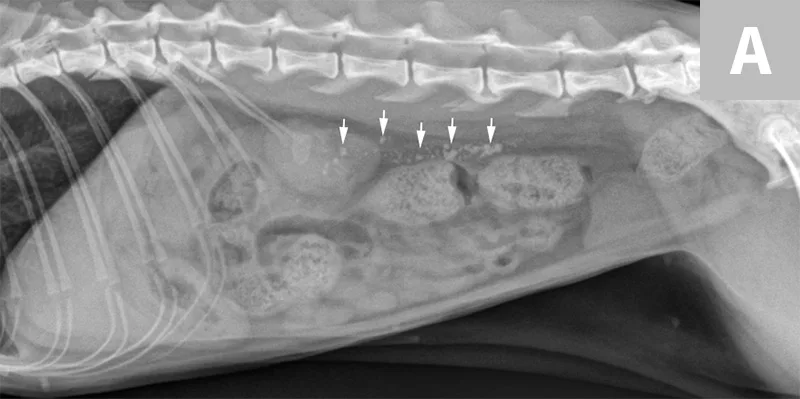

Figure 5A Lateral abdominal radiograph of a dog with 2 well-defined, oval mineral opacities superimposed over the retroperitoneal space caudal and dorsal to the kidneys (arrows). Based on the ventrodorsal projection (not shown), these calculi were likely to be associated with the right ureter.

Ureteral calculi are a common cause of ureteral obstruction; localization of ureteral calculi is imperative prior to choosing appropriate management. While ureteral calculi have been reported as the most common cause of ureteral obstructions, other causes such as iatrogenic ligation, blood clots, tumor, strictures (congenital and acquired), solidified blood stones, and a circumcaval ureter have been reported.4-7

The obstruction can be located at any point of the ureter and can vary in severity. Normal ureters are typically not seen on ultrasonography due to their small size. The easiest way to locate a dilated ureter is to trace the ureter from the renal pelvis. In most cases, the ureter is dilated proximal to the site of an obstruction and tapers to a more normal appearance distal to the site of obstruction. Imaging can also reveal retroperitoneal effusion which can result from ureteritis and possible urine leakage.

Potential indications for removal of renal calculi in dogs include obstruction, recurrent infection, progressive calculi enlargement, presence of clinical signs (renal pain), and patients with calculi in a solitary functional kidney.8 The most common indication for removal of calculi in cats is obstruction caused by ureteral calculi.9

Nonobstructive renal calculi in cats is not typically treated unless the obstruction moves into the ureter and causes ureteral obstruction. Nonobstructive renal calculi usually have minimal impact on progression of chronic renal disease in cats, so the presence of calculi alone is not justification for treatment in cats.10

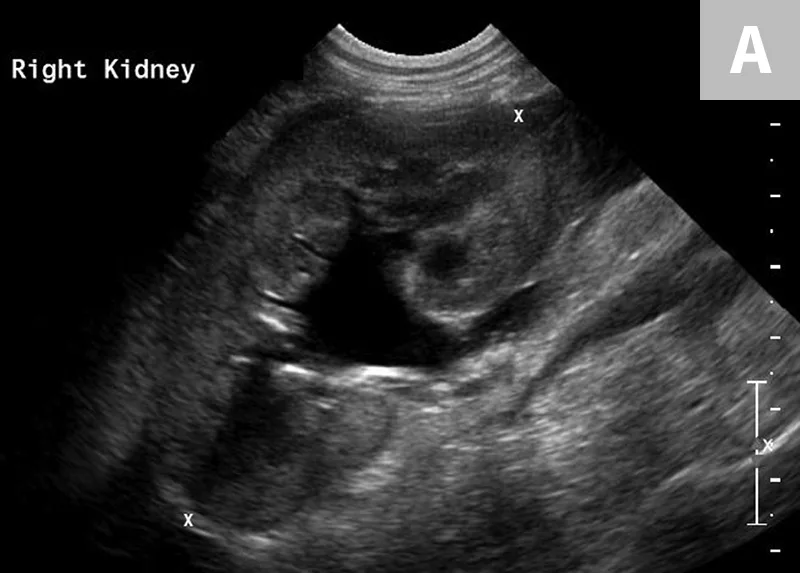

Clinical signs associated with ureteral calculi may range from chronic non-specific signs to acute or chronic renal failure. The presence of hydronephrosis can be highly suggestive of a ureteral obstruction (Figure 6).

Figure 6A Mild to moderate right hydronephrosis and proximal ureteral dilation in a Dalmatian.

Differentiation between a complete vs partial ureteral obstruction can be difficult with survey radiography and ultrasonography alone. Antegrade pyelography (nephropyelocentesis with renal pelvic injection of iodinated positive contrast medium using ultrasound guidance) may be useful for documenting a complete vs partial obstruction (Figure 7).11

Figure 7A Lateral abdominal radiograph of a cat with multiple, small, oval mineral opacities superimposed over the ventral aspect of the retroperitoneal space (arrows). These mineral opacities are arranged linearly extending from the caudal aspect of the kidneys to the level of the urinary bladder.

Antegrade pyelography is beneficial when compared with standard IV urography, as it lowers the risk of potential contrast-induced renal damage and provides excellent filling of the renal collecting system, regardless of renal function.11

Calculi of the Urinary Bladder & Urethra

Calculi formation within the urinary bladder occurs from a variety of inherited and environmental conditions, and management is often imperative.7 Radiographic detection of urinary bladder calculi has up to 87% sensitivity with improvement to 95% when used in combination with positive-, negative-, or double-contrast cystography.15

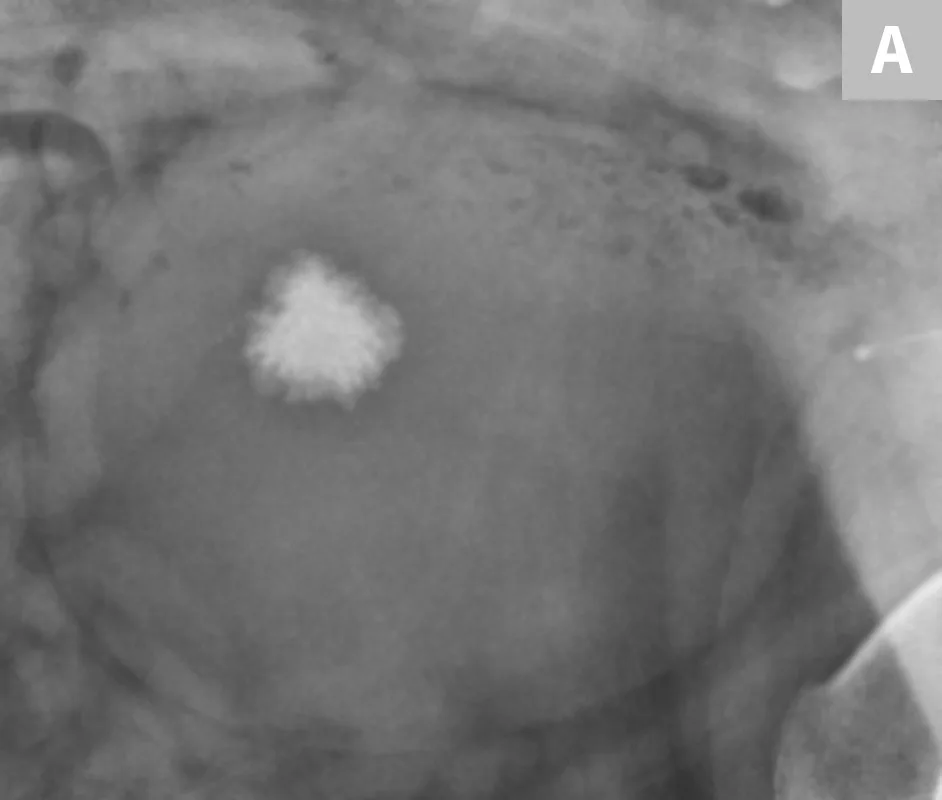

The lower detection rates for survey radiography are largely due to the variations in the chemical composition of different calculi. The most common types of calculi in small animal practice are struvite and calcium oxalate; both are mineral opaque (Figure 8).13,14,16,17

Figure 8A Lateral radiograph of the urinary bladder in a dog with a confirmed calcium oxalate calculus. This calculus has a very irregular margin often seen with calcium oxalate calculus formation.

Cystine and urate calculi are less common overall, but more common in bulldog and dalmatian breeds, respectively. These are often non-mineral opaque and are unable to be visualized with survey radiography alone.18 One helpful mnemonic for remembering the non-mineral opaque calculi is “I can’t C U.” Cysteine and urate calculi cannot be visualized as they often do not mineralize. For non-mineral opaque calculi, contrast cystography or ultrasonography will aid in detection (Figure 9).

Figure 9A Lateral radiograph of a bulldog presented for recurrent hematuria and stranguria. The study was negative for mineral opaque urinary bladder calculi.

Urinary bladder calculi can also descend into the urethra, which can potentially lead to urethral obstruction. In male dogs, it is imperative that the entire urethra is included within an additional radiographic image using the appropriate collimation (Figure 10).

Figure 10 Lateral radiograph of a male dog centered on the perineum with the pelvic limbs pulled ventrally (flexion of the pelvis at the coxofemoral joints). This radiograph documents multiple well-defined, mineral opaque calculi within the penile urethra (arrows).

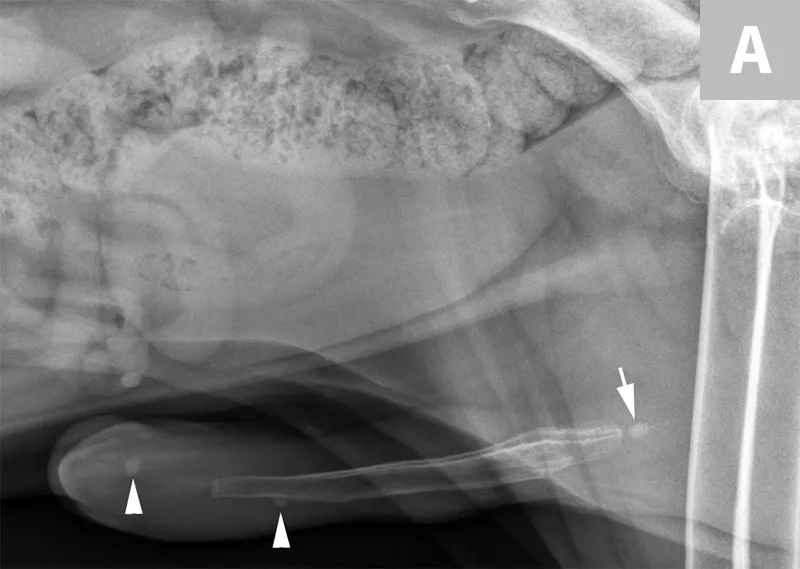

A separate center of ossification associated with the os penis may mimic a urethral calculus (Figure 11 A and B). A separate center of ossification can be seen at either end of the os penis and will be in line with the os penis. A calculus within the penile urethra would be seen ventral to the os penis in the location of the urethra. Contrast urethrography can be a helpful way to differentiate between a separate center of ossification and urethral calculus (Figure 11C).

Figure 11A Lateral radiograph of a male dog collimated to include the urinary bladder and os penis. Note the well-defined mineral opacity just proximal to and at the same level as the base of the os penis—a separate center of ossification (arrow). Also note the two soft tissue opaque nodules summating with the prepuce, presumed to be small nipples (arrowheads).

Conclusion

Radiography and ultrasonography can provide information related to anatomic changes that are present within the kidneys. This includes changes in renal size, shape, and margination. Ultrasonography can help identify and differentiate between the presence of renal dystrophic mineralization and renal calculi. Contrast radiography can also supplement these imaging modalities for visualization of obstructions of the ureters or urethra or the presence of non-radiopaque (non-mineralized) urocystoliths.

Editor's note: This article was originally published in May 2017 as "Imaging of Calculi of the Urinary System"