Canine & Feline Pain Scales

Ashley J. Wiese, DVM, MS, DACVAA, MedVet

Persistent or untreated pain can predispose patients to disease, prolong hospital stays, increase treatment costs, and impact ethical concerns surrounding patient care. The ability to manage pain appropriately relies on the intent to look for it, the ability to recognize it, a means for quantifying it, and a system to determine the efficacy of treatment.1

Background

Anonymously surveyed clients considered pain management vital to their pet, and 81% demonstrated an appreciation of the negative impact of pain on their pet’s quality of life.2 To help establish pain assessment as the fourth vital sign, the Global Pain Council developed the Global Pain Council Guidelines.3 Despite the evident importance of pain management as established by clients and veterinary professionals, and despite advancement in management strategies, pain is still largely undertreated.2,4

Veterinary care providers must become familiar with characteristic pain behaviors in order to detect, categorize, and manage pain effectively in nonverbal species (see Common Behavioral Pain Indicators).5-7 There are a number of important pain assessment limitations even for experienced observers to remember. Not all patients display behaviors indicative of pain, but this does not mean a patient is not experiencing pain. In addition, independent factors may influence pain behavior (eg, species, age, behavioral challenges [eg, aggression], concurrent disease, patient environment [eg, white coat effect]).

Common Behavioral Pain Indicators5

Pain Assessment

Objective, validated pain scoring systems should be used to optimize pain detection and therapeutic intervention. There currently are no gold standard pain scales for dogs or cats; however, there are a myriad of scales that range from basic to more complex. Ideal characteristics of pain assessment scales include ease of use, efficacy, repeatability, lack of bias, and reliability across varying levels of education.

Unidimensional Pain Scoring Scales

Examples of basic pain assessment scales include the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Simple Descriptive Scale (SDS), and Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). These unidimensional scales are easy to use and can trend scores over time, but they risk interobserver variability and lack objectivity in quantification of pain, in addition to imparting observer bias (eg, number bias).

Subjective Verbal Scoring Systems

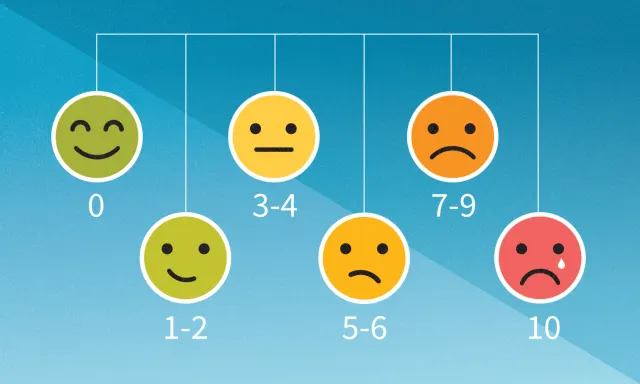

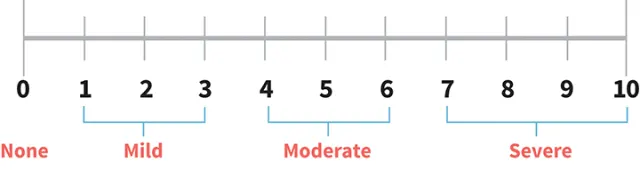

Basic pain scoring scales are simple to use but have inherent limitations. Subjective verbal scoring systems use a simple approach of assigning words to classify pain (eg, no pain, mild, moderate, severe pain), or an assigned number to gauge the presumed pain the animal is experiencing.

Visual Analogue Scales

VASs are used widely in veterinary medicine and can be numeric or non-numeric. The scale consists of a horizontal line measuring 100 mm with a vertical line border at both ends (see Figure 1). Identifiers such as “no pain (0)” at the left border and “worst possible pain (10)” at the right border are usually present. VASs may have segmental dividers or descriptors placed along the horizontal line, but these versions are prone to bias and are not recommended. A VAS provides a greater range of scoring options, making it slightly more discriminatory than subjective numeric scoring scales.

Visual Analogue Scale

Simple Descriptive Scale

The SDS assigns descriptors to a limited number of pain severities, thereby providing greater objectivity than a subjective verbal scoring system. The descriptors are often assigned a number with increasing values indicating increased severity that is used to establish the animal’s pain score. Numerous SDS versions are applied with descriptors ranging from basic (eg, none, mild, moderate, severe) to more detailed versions with brief definitions to describe each descriptor (eg, anxious, depressed, aggressive, uncontrollable).

Numeric Rating Scale

NRS is another type of scale that assigns numeric values to indicate pain severity. To quantify a gradual increase in pain intensity, an NRS offers multiple (≤10) numeric categories with descriptors for each category (ie, physiologic [eg, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure], descriptive). Scores from each category are totaled to an overall pain score, but individual categories are not weighted by importance (see Figure 2).

Numeric Rating Scale

Multidimensional Pain Scoring Scales

Multidimensional (ie, composite) scales that incorporate quantitative measurements of pain behaviors can offer the most objective, repeatable, and robust assessments of pain.8 There are a number of multidimensional (ie, composite) pain scale examples that are canine- and feline-specific. Multidimensional scales include assessment of both spontaneous (ie, unprovoked) and evoked responses when categorizing pain severity. (See Acute Pain Measurement.)

Multidimensional pain scales categorize, group, and weigh observer interpretations of pain. Individual categories are added to form an immediate pain score that can be tracked over time to evaluate pain management efficacy. This system assigns importance to key behavioral and physiologic variables. Although multidimensional pain scales are considered some of the most robust, they are still limited by different definitions or descriptors derived by different authors, in addition to how the scale is applied clinically.

Acute Pain Measurement

A validated, commonly used multidimensional pain scale used in clinical practice with forms available for both dogs and cats is the short form of the GCMPS, available at newmetrica.com/acute-pain-measurement.

Composite Pain Scales

The Glasgow Composite Measures of Pain Scale (GCMPS) has been validated for acute orthopedic or soft tissue pain as well as medical conditions in dogs and has been adapted into a practical and easy short form. The GCMPS has been validated for use in cats, and the UNESP-Botucatu Multidimensional Composite Pain Scale is being validated for acute, post-operative pain in cats.9-11

Additional Pain Scale Options

Grimace Scales

Grimace scales have been developed for a number of species, including humans, rodents, horses, rabbits, and cats.12 These scales use interpretation of facial expressions to determine pain severity. These scales have not been widely adopted in clinical practice.

Client Assessments

Client-based pain assessment is another approach for measuring pain, often through a questionnaire. The Canine Brief Pain Inventory (CBPI) is one such tool designed to quantify the severity of pain and its impact on quality of life in dogs with osteoarthritis or bone cancer. The questionnaire averages the response to 4 questions scored from 0 to 10 to generate a pain severity score. Interference of patient pain with daily functions is measured by averaging the score of 6 questions scaled from 0 to 10.

A limitation of any pain scale with behavior assessment is the influence of disease (eg, depressed mentation), nonpain behavior (eg, aggression), or drugs (eg, sedatives, post-anesthesia)—this must be considered to ensure therapeutic interventions are appropriate. For effective pain assessment, appropriate information on normal pet behaviors from a client, knowledge of the patient’s health status, and anticipated drug influence duration with potential behavior-modifying effects are necessary details.

Application of Pain Assessment & Scoring Scales

The most effective pain scoring scale for the practice should be selected based on the team’s specific needs. Regardless of the scale implemented, the importance of assessing spontaneous (ie, unprovoked) and evoked pain cannot be overemphasized.

Successful implementation in the practice requires training all individuals involved in pain assessment (ie, veterinarians, veterinary nurses, veterinary assistants) and consistency in application. AAHA recommends that pain be assessed on all patient visits, including outpatients.8 Pain should be assessed in every patient after temperature, pulse, and respiration. Postoperative patients should be evaluated for pain hourly for the first 4 to 6 hours after surgery, considering mentation and anesthetics, then every 4 to 6 hours until discharge.

Trigger points for therapeutic interventions should be determined for the pain scale that is implemented. For example, a score >6 on the GCMPS or a moderate or higher score on an SDS should trigger an intervention. Therapeutic interventions may be pharmacologic (eg, opioid, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory) or nonpharmacologic (eg, positioning/padding adjustment, walk to allow urination or defecation, ice or heat pack, integrative therapy).

Conclusion

Pain assessment tools enhance the care of perioperative patients. Routine implementation of a pain scoring scale can enhance the team’s comfort with pain assessment, leading to improved patient care.

CBPI = Canine Brief Pain Inventory, GCMPS = Glasgow Composite Measures of Pain Scale, NRS = Numeric Rating Scale, SDS = Simple Descriptive Scale, UNESP = Universidade Estadual Paulista, VAS = Visual Analogue Scale

This article originally appeared in the October 2018 issue of Veterinary Team Brief.