Pet Cats & Toxoplasmosis Risk For the Immunocompromised

You have asked...

How do I advise people with immunocompromised family members about the risks and prevention of toxoplasmosis? Is relinquishment really necessary?

The expert says...

Those at increased risk for infections typically involve “YOPIs”: young (<5 years of age), old (>65 years of age), pregnant, and immunocompromised. Toxoplasma gondii causes much concern because of its ability to cause, in some situations, devastating infections, leading some physicians to recommend removal of pet cats from the household. But when, if ever, is removal justified, and what can be done to reduce the risk for zoonotic transmission?

When, if ever, is removal of pet cats from the household justified, and what can be done to reduce the risk for zoonotic transmission?

T gondii Basics

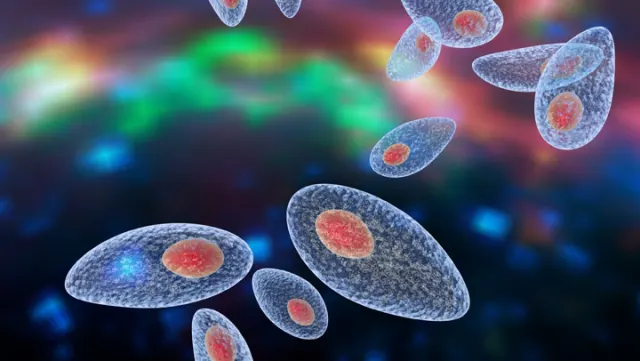

T gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoal parasite distributed worldwide. Domestic cats and other felids are definitive hosts, and sexual reproduction of the parasite results in shedding of massive numbers (3 million to 810 million per infection)1 of unsporulated (noninfectious) oocysts in feces. Oocyst shedding typically occurs over only 3 to 10 days in naïve cats,2 after which the enteric life stage in that animal is completed. Oocysts sporulate in the environment over a period of 1 to 5 days, at which point they become infectious.3 When infectious (sporulated) oocysts are ingested by another host (including humans), sporozoites hatch in the small intestinal lumen and penetrate the intestinal wall. Sporozoites then divide asexually and become tachyzoites, which reproduce rapidly within tissues—most often in the central nervous system, muscles, and visceral organs.

They typically cause no clinical signs and exist in a viable but dormant stage. Disease can develop based on the number, size, and location of cysts. Reactivation of latent infection can occur at any time, typically following immunosuppression, and cause further dissemination of cysts and, potentially, disease. The life cycle continues when felids ingest tissue cysts from prey, although cats can also be infected transplacentally and through milk.

Key Points

Toxoplasma gondii in Cats

In cats, T gondii exposure is common and presumably first occurs early in life. The most likely source is ingestion of tissue cysts while hunting rodents,4,5 so it is not surprising that seropositivity in cats is more common in strays than household pets.5-7 Although seroprevalence rates are high (16%-61%) in cats,4,5,7-10 shedding of oocysts is rare, with rates of 0.1% to 0.9% typically reported.10-13 This relates to the common pattern of cats becoming infected early in life, shedding oocysts for only a short time, then becoming relatively resistant to future infection.

It has been widely reported that cats do not shed oocysts after initial infection, and this is likely true in most cases; however, shedding after re-exposure occurring many years after the initial exposure has been reproduced experimentally.2 Whether this is relevant to the natural situation is unclear, but it is prudent to assume that any cat could be shedding T gondii oocysts at any time and use appropriate preventive measures. Waning immunity probably plays an important role in the potential for reinfection and shedding of oocysts, so there may be disease, age, or drug (eg, immunosuppressant therapy) factors that increase the likelihood of a re-exposed adult cat shedding oocysts.

Toxoplasmosis in Humans

Concerns about toxoplasmosis revolve mainly around 2 groups: immunologically naïve (seronegative) pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals. In other humans, Toxoplasma gondii exposure typically results in seroconversion with no disease. Fetal infections can be devastating, resulting in fetal loss or stillbirth.14

In immunocompromised individuals, toxoplasmosis concerns largely emerged during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Cerebral toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma spp encephalitis) became a serious problem in HIV-infected individuals before highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) was available. Classified as an AIDS-defining-disorder,15,16 cerebral toxoplasmosis had an annual incidence of approximately 33% in seropositive patients not treated prophylactically.17 Cerebral toxoplasmosis was estimated to be the cause of death of at least 10% of individuals with AIDS.15 However, even in highly immunocompromised individuals, the incidence of cerebral toxoplasmosis was relatively low in seronegative individuals. This highlights the fact that disease predominantly developed as a result of recrudescence of latent infection, not acute infection. That there was no difference in seroprevalence between HIV-infected cat-owners vs non–cat-owners18 further supported the notion that acute infection from cats was rare.

Although AIDS patients are likely the highest (or at least best-defined) risk group, individuals who are profoundly immunocompromised for other reasons—particularly those severely compromising cellular immunity (eg, following solid organ or bone marrow transplant, those undergoing aggressive immunosuppressive therapy for other disorders)—may also be at high risk for clinical toxoplasmosis.19 Yet, as with HIV-infected individuals, the risk is mainly from reactivation of latent, not acute, infection. Recently, much attention has been drawn to linking toxoplasmosis to schizophrenia or mood disturbances20,21; however, evidence is limited and results have been questioned.22

Is Cat Contact an Important Source of Toxoplasmosis?

Because cats are the definitive host, it is logical to assume that cat contact would be an important risk factor; however, ingestion of raw or undercooked meat is the most commonly identified risk factor, and there is limited information implicating contact with pet cats as an important cause of exposure or disease. Domestic-cat exposure has been identified as associated with acute toxoplasmosis or seroconversion in some studies,23-26 either overall or only among rural residents.27

However, other factors (eg, diet, low socioeconomic level, poor hygiene status, degree of soil exposure) are more common or typically have stronger associations.26,28-30 Further, many studies have been unable to identify an association between cat ownership and toxoplasmosis or T gondii seropositivity in humans.30-32 Veterinary students and veterinarians (who presumably have much more cat exposure) do not have significantly higher T gondii seroprevalences.33-35 The lack of an association of cat ownership with cerebral toxoplasmosis in individuals with AIDS also highlights the fact that the main risks do not include cat ownership or routine cat contact.

Prevention & Control

Although the risks associated with toxoplasmosis must not be dismissed, they must be approached in a balanced manner. Conversely, while the risks are low, the severity of disease dictates a need to be proactive. The low risk of exposure from a pet cat can be decreased further using some practical infection-control practices (see Preventive Measures in High-Risk Households). Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines for prevention of toxoplasmosis in HIV-infected humans17 recommend avoiding raw or undercooked meat, washing hands after contact with meat or soil, washing fruits and vegetables, and either having someone else change their cat’s litterbox or washing their hands thoroughly after litterbox cleaning if they must do it themselves. These guidelines also recommend that HIV-infected individuals do not adopt or handle stray cats and do not feed raw or undercooked meat but specifically state that “patients do not need to be advised to part with their cats or to have their cats tested for toxoplasmosis.” Guidelines for pregnancy take a similar approach and do not recommend removal of cats from the household.36 Because individuals with HIV and pregnant women are the highest-risk groups, there is no reason for any more aggressive measures (eg, cat removal) in other high-risk human populations.

The overall incidence of zoonotic infections associated with pet cat contact is low, risks can be reduced with practical measures, and pets can offer many health and emotional benefits.

Is Removing a Cat From the Household a Reasonable Response?

Rarely, if ever, is removal of a low-risk cat from a household a justifiable response. Although zoonotic infections are an ever-present risk, the overall incidence of zoonotic infections associated with pet cat contact is low, risks can be reduced with practical measures, and pets can offer many health and emotional benefits. The risk of acquiring T gondii from a pet cat is low, and it can be reduced to almost negligible levels through basic cat management and hygiene practices.

Preventive Measures in High-Risk Households